All true students of the Earhart disappearance are familiar with the July 24, 1949 Los Angeles Times interview with Amy Otis Earhart, Amelia’s beleaguered mother. In the Times story, headlined “Amelia Earhart Killed in Japan, Says Mother,” Amy told an unidentified reporter, “I am sure there was a government mission involved in the flight, because Amelia explained there were some things she could not tell me. I am equally sure she did not make a forced landing in the sea. She landed on a tiny atoll – one of many in that general area of the Pacific – and was picked up by a Japanese fishing boat that took her to the Marshall Islands, under Japanese control.”

Amy could have learned all of the above from an Associated Press story penned by reporter Eugene Burns and published March 21, 1944, which was then picked the next day up by many papers nationwide including the New York Daily News, New York Sun and Oakland Tribune. The 1944 story, which should have been a blockbuster, made no impression on a nation still locked in the grip of war, with no time to worry about what happened to Amelia Earhart — not much different than our current zeitgeist, come to think of it.

After Fred Goerner returned from his first Saipan visit in July 1960, he heard the story of Amelia’s Marshall Islands landing from former Navy men John Mahan, Eugene Bogan, Charles Toole and Bill Bauer, and he presented it to America in his 1966 bestseller, The Search for Amelia Earhart. Readers can find the details there or in “The Marshall Islands Witnesses” chapter of Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last.

Amy Otis Earhart sadly contemplates a painting of her daughter in a photo taken May 21, 1947 at her home in Medford, Mass. In May 1944, more than a full month before American forces found Amelia Earhart’s plane on Saipan, Amy wrote in a letter to Neta Snook Southern, “You know, Neta, up to the time the Japs tortured and murdered our brave fliers, I hoped for Amelia’s return; even Pearl Harbor didn’t take it all away, though it might have, had I been there as some of my dear friends were, for I thought of them as civilized.”

Getting back to Amy Otis Earhart: Writing in May 1944 to Neta Snook Southern, Amelia’s first flight instructor, she shared facts and insights she didn’t get from Burns’ AP story of a few months earlier. Beginning with a reference to Marshallese native Elieu Jibambam’s account to Lieutenant Eugene Bogan via the Japanese trader Ajima, Amy launched into what has become a legendary diatribe, and one that emphatically reveals that the so-called “Earhart Mystery” held no such allure for Amelia’s good mother. I present it below, sans a few irrelevant paragraphs, for your edification. Boldface emphasis mine throughout.

Mrs. Amy O. Earhart,

2282 Union Street

Berkeley, 4, California

May 6, 1944

My Dear Neta,

I am sorry I have had to be so long in answering your letter — but whenever a new story or rumor about Amelia starts, I am simply lost under the letters that pour in from everywhere. This story came through the Associated Press whose representative here told me they stood ready to vouch for the story, had checked and rechecked on not only the Lieutenant, but had their representative in the south sea area where the native lived, see and talk with him also.

The Jap trader who is the weak link in the claim isn’t doing much trading around just now, so whether the story he told the native is really true, or was fact, rumor, or hearsay he was repeating, cannot be checked on now.

It does happen to fit in with information brought me by a friend a few days after Amelia’s S.O.S who was listening to a former schoolmate’s short-wave radio when a broadcast from Tokyo came in saying they were celebrating there, with parades, etc. because of Amelia’s rescue or pick up by a Japanese fisherman. That was before the war you know, and evidently the ordinary Jap had no knowledge of their military leaders’ plans so were proud of the rescue and expected the world to be. That young girl drove 27 miles at 11 o’clock at night, and through a horrid part of Los Angeles to tell me. It was too late when she arrived at my house in North Hollywood, but the next day I went with her to the Japanese Consulate in Los Angeles and asked him about it.

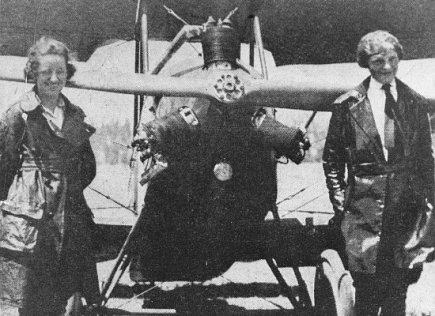

Amelia Earhart began her flying career at the age of 23, when she started taking flying lessons in Long Beach, Calif., from Neta Snook, left, earning her pilot license at the age of 26. Amelia was only the 16th woman to become a licensed pilot. Early in January 1921, Amelia took her father to Kinner Field, a small dirt airstrip in the South Gate area of Los Angeles, and approached Snook. “I’m Amelia and this is my father,” Snook recalled in her 1974 book, I taught Amelia to fly. . . . “I want to learn to fly and I understand you teach students. . . . Will you teach me?” Neta and Amelia are pictured above with Amelia’s first plane, a Kinner Airster.

He was very pleasant and said he had been out the night before, so hadn’t heard the broadcast, and would take it up with the government at once, and it might take time to get the details, and we should come the morning of the second day, when he would tell me all about it, if it wasn’t in the newspapers by that time, and advised us not to tell it about, until we had seen him again. When we went back, a stranger was there — said he was the new Consul, had just come in via the boat the day before, and the former Consul had left via the same boat for Tokio [sic] that morning — He knew nothing about it — Mr. Putman came home the next day and finally got in touch the Jap, and not getting any satisfaction over the telephone, insisted on a personal interview and saw the Consul, but got nowhere and came home angry and mad.

We tried to get an inquiry made from Washington but could get no further than with the Jap, and they were all stirred up about the search order made for her, and getting that started. The search, when it finally arrived near the islands, were [sic] not permitted, any more than our small boats there, to search the Marshalls, Carolines, or Marianas groups under the Jap mandate, but were told the natives were not friendly, and that the Japs would man boats and search everywhere themselves, and they did, and in some cases received thanks for their cooperation.

Many other things have come to me from time to time from people interested and who no more believe she crashed into the sea than I did. I have thought for some time she was being kept a prisoner there, because of what she saw and which they knew would be reported if she didn’t have an accident happen to her, which did to several sent by the government to see if those islands were not being fortified.

It all fell together as small pieces came in and makes a story. I have said very little about much that I have gathered and especially about that connected with the Jap prisoner side of it, except to a very few close-lipped friends, not even telling Muriel for I couldn’t check up on it and had no desire to start rumors which would worry Muriel, as it often does me and Amelia’s friends, whom I sometimes think includes most of the world.

I am writing this to you because I realize that a great part of your heart is down that way, too, as your boy goes back and forth in his work for his country and know, too, how many the anxious days and hours you keep within yourself as you go about your duties, just as I have tried to do always. One learns to manage the outside, but the inside is something we cannot always do so well with for it takes a lifetime of experience and practice. It does give us something of that understanding heart, which is so sorely needed in the world and which, together with patience, will be a necessity of this new world we dream of making.

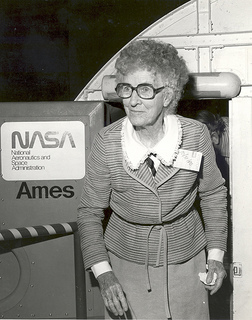

Neta Snook Southern, age 84, emerges from the Flight Simulator for Advanced Aircraft at Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif., sometime in 1980. Neta was the first woman aviator in Iowa, first woman student accepted at the Curtiss Flying School in Virginia, first woman aviator to run her own aviation business and first woman to run a commercial airfield. Yet “Snookie,” as her friends called her, was destined to be remembered for her relationship to Amelia Earhart. Her autobiography I Taught Amelia to Fly aptly captures the essence of her fame; she was forever linked to the Earhart mystique as her first instructor. Neta died in March 1991 at the age of 95.

You know, Neta, up to the time the Japs tortured and murdered our brave flyers, I hoped for Amelia’s return; even Pearl Harbor didn’t take it all away, though it might have, had I been there as some of my dear friends were, for I thought of them as civilized. There were times when, inside, I was wild with anxiety as I thought what might be happening to her, but gradually quieted myself with the thought they would (be) more likely to hold her as a hostage, and exchange her for some of their own they wanted, maybe might let her come home after the war was over, well and unharmed, just to show they were not (to) [sic] the brutes we thought them — but, when that story came out from our own men who had seen it all with their own eyes, and afterward escaped from their prison camp to tell of it, I thought so no more.

So the hope is only the finding out what happened after the Jap fishing boat picked her up from the small island where she had landed. One can face anything she knows is so, but unless she goes through the torture of not knowing, it is not possible to understand the agony connected with uncertainty, nor the loopholes it leaves for the imagination to get in its work.

I often think of the lights kept burning in the windows along the New England coast, here and there, often for a lifetime, put there to guide the fishermen safely home, a goodly number for those who will never come, but uncertainty keeps it burning. One clings to hope or perhaps it is just the feeling she wants the welcoming light, or the sign of the welcoming hand there, while she is here. At any rate, mothers understand it and a good many fathers, too.

. . . This is growing into a booklet, and I must stop. I am glad to hear your mother keeps well, and I think she was not only a patriotic mother not to try the trip out here, but a very wise one. Some of my friends who were here from Boulder, Colorado last week as well as others, tell tales of very uncomfortable times even in the drawing room sleeping cars, and it is impossible to get a reservation on a plane. I hope you keep well yourself, and keep hearing good news from your boy.

Affectionally [sic],

Amy Otis Earhart

Amelia met Eleanor Roosevelt at a White House state dinner in April 1933, and they were said to have “hit it off” immediately. Near the end of the dinner, Amelia offered to take Eleanor on a private flight that night. Eleanor agreed, and the two women snuck away from the White House (still in evening clothes), commandeered an aircraft and flew from Washington to Baltimore. After their nighttime flight, Eleanor got her student permit, and Amelia promised to give her lessons. It never happened.

Amy’s letter was sent to Bill Prymak by researcher Art Parchen. After reading the full transcript of her Los Angeles Times interview, Parchen concluded that the source of Amy’s uncanny knowledge about her daughter’s death may have been Eleanor Roosevelt – who Parchen, among others, believes enjoyed a special relationship with Amelia Earhart. “Eleanor Roosevelt told Amelia’s mother what happened out of compassion for her anguish,” Parchen wrote in his August 1994 letter to Prymak and the Amelia Earhart Society. “It was her way of ‘giving something back’ to the mother of the woman who taught her how to fly. You cannot read the L.A. Times interview without being convinced that Amy Otis Earhart really KNEW and ‘had it on good authority.’ ”

Parchen, who passed away at 85 in 2012, may have nailed it. Eleanor Roosevelt could well have known of Amelia’s death or capture by the Japanese, and if so, it means President Franklin D. Roosevelt knew the truth long before U.S. military forces found Amelia’s Electra in a hangar at Aslito Field on Saipan in the summer of 1944, something many researchers have long suspected.

But Amy also made a few very questionable statements in that 1949 Los Angeles Times interview, fanciful claims that couldn’t possibly have originated with Eleanor Roosevelt. Amy’s insistence that she knew Amelia “was permitted to broadcast to Washington from the Marshalls,” and “Amelia’s voice was recognized in the radio broadcast from the Marshalls to the U.S. capital,” seems most unlikely, although Parchen uncritically accepted these statements as true.

Strictly from a layman’s perspective, I would think that a short-wave radio transmission powerful enough to reach Washington from the Marshall Islands should have been heard by more than the few who reported hearing messages over several days. And why would the Japanese allow Amelia to broadcast from the Marshalls, only to deny all knowledge of her whereabouts soon thereafter, and later were found to have lied about the role their seaplane tender, Kamoi, played in the initial search effort? Stranger things have happened, I suppose.

Many little mysteries can be found when one studies the disappearance of Amelia Earhart. But none of these puzzles can obscure the big picture, the one that so clearly reveals her landing at Mili Atoll and eventual death on Saipan. This is what our media refuse to acknowledge, and so they continue with their endless propaganda that so vexes the few of us who truly care.

Amy Otis Earhart passed away at age 92 in 1962 in Medford, Mass., but her 1944 letter to Neta Snook lives forever in Earhart lore as one of the most compelling indications that the U.S. government was lying about what happened to Amelia from the earliest days.

![Fishing boat story 5 This story appeared at the top of page 1 in the July 13, 1937 edition of the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania)-Globe Times. “Vague and unconfirmed rumors that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan have been rescued by a Japanese fishing boat without a radio,” the report began, “and therefore unable to make any report, found no verification here today, but plunged Tokio [sic] into a fever of excitement.” The story was quickly squelched in Japan, and no follow-up was done. (Courtesy Woody Peard.)](https://i0.wp.com/earharttruth.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/fishing-boat-story-5.png?w=616&h=352&ssl=1)

Wow, Mike. This letter almost breaks my heart. I can really sense the wistfulness and pain and hesitancy to relinquish all hope. Thanks for posting this – I do remember it from your most excellent book. If any readers of this blog have not yet purchased and read your book, this is just one more of many nudges in that direction.

LikeLike

Thanks for the informative post, Mike. It feeds into one of my speculations. Which is that FDR took a very dim view of the friendship between Amelia and Eleanor. I picture Amelia not especially impressed by FDR, in fact, taking Eleanor’s side in their apparently rocky marriage. This might account for FDR’s negligent treatment of Amelia’s plight. The vindictive president was not at all concerned, even pleased at her situation. As evidenced by his reaction overheard by the page. Of course he decided to leave her to her unpleasant fate and made sure it was covered up in order to conceal his callous actions. Not so much to influence the 1944 election but to ensure his exalted historical reputation. Perhaps, to go way out on a limb, maybe the whole flight was his devious way to “fix her”. I know my interpretation invites being scoffed at, but you’d be surprised at what evil lurks in the heart of man sometimes.

LikeLike

Stranger things have happened, David. It is truly appalling at how cruel some people can be when they believe they have the upper hand over someone for whom they hold a deep grudge. Petty. And plausible.

LikeLike

I thought the same exact thing…. FDR figured he didn’t like AE’s influence on Eleanor anyway!

LikeLike

Why wouldn’t Amy elevate the issue of the Japanese broadcast of her rescue ? To Putnam in ’44? To the State Department, to the American Occupation Forces in Japan post war ? For serious investigation. Or a request for a personal meeting with Eleanor Roosevelt – one on one – so a mother (Amy) could learn the truth about her daughter (Amelia). Post war. Or ask Jackie Cochran for assistance? Her Senator? Her Congressman?

I think if Amy knew the real truth, she would have said so. There’s nothing to be gained by ambiguity.

LikeLike

Who knows that she didn’t try to do some of those things, and was roundly ignored? Or that she might have been told the truth on the condition that she keep quiet about what she knew? Are you doubting the veracity of this letter? Do you think I made it up?

LikeLike

I thought I read in “The Truth” that the Japanese quickly answered that the report was a mistake. Denied having found anyone. Weren’t they very suspicious how their newspaper got the story? Wasn’t it a case where the news came from one of their diplomats who had actually heard it from a non-government source and the Japanese government immediately suspected that their code had been broken? I agree that the whole incident was embarrassing to both the USA and the post-war Japanese government. All they needed to say to Amy was that we were in a war and nobody appreciated her input, please keep your mouth shut this is an issue of “national security” and Amy, being a good citizen said 10-4 Mr. Roosevelt. For all we know Eleanor spoke with AMY and confirmed it would be best for all concerned if Amy would keep it to herself. I wouldn’t be surprised if the inner circle (like the inner circle that suckered Japan into mounting their sneak attack) knew exactly what happened to her and when. Might have informed Amy that AE died on a certain date and moreover, they were digging up the bodies and would send them back to the States so Amy could have the remains if she just kept quiet. Which is what she mostly did, I guess. Just my speculation again.

LikeLike

Thanks David, your speculation is well founded. We’re nearly certain that FDR knew the Japanese had Amelia within four months of her loss. We had broken all their codes in 1937 and that’s how long it would have taken to get the intercepted transmissions back to Washington and decoded, according to an expert who’s studied the situation closely.

LikeLike

I find it interesting that Amy speaks of “the SOS” as if it were a fact. I believe that AE was certainly able to get off some messages after she landed her plane based on all I have read. Maybe Amy was being kept “in the loop” at least for a while. Then as events unfolded, FDR told the Navy to quash the story for whatever reason. I am not so quick to disbelieve the story of AE sending radio messages to Washington. Perhaps it was not a “broadcast” but a affirmation by the Japs that they really had her and wanted something in return for her release. To which FDR replied “Nuts” as that general in the war supposedly said or more likely “Bleep her” if the story about his reaction were true. Since the country needs its heroes, why would anyone want to besmirch his reputation with a story of him being an SOB to the heroine? Who would want to believe that?

Methinks I speculate too much.

LikeLike

David C ( Too many Davids here !! )

:

I do not doubt the letter. as stated. The reality of it rests with the day after Japan surrendered unconditionally in September 1945. At that point, Roosevelt is dead, the Japanese Codes are irrelevant, and there is really no need for a secret as minor as Amelia serving as an intelligence asset, if she did. You can grill as many Japanese as you want about Earhart. Eight years later is a long time. Truman’s the President. Had no real love for FDR. Wasn’t even advised about the Atomic Bomb development. There were certainly enough people who would advocate on Amy’s behalf, spontaneously. I simply don’t view it as the classic death bed promise to a deceased President. If she knew it, she should have pushed the envelope on it. Nothing to lose, and everything to gain.

Also, exactly which Japanese codes were broken in 1937 ? I believe that this did not occur until 1941.-The Diplomatic Code only.

PS: “David A.” : I believe it was no great secret that FDR could have cared less about Eleanor. Didn’t he have a mistress ( A secretary ?) His public image while living was unblemished. .

Also, FDR was more concerned about MacArthur running on the Republican Ticket against him in 1944. Hence his trip to Hawaii – a PR Masterpiece:” FDR, Nimitz, and MacArthur conferring on the plan to defeat Japan.”

LikeLike

There is no mention of Bernard Baruch’s meetings with Amelia in his biography. I am inclined to assume the worst about those meetings.

LikeLike

Way to go Mike ! You now know I am your newest, biggest fan and newest friend. It nice to read the truth instead of the contempt for truth I get from the Smithsonian! I just crossed that scummy magazine of my list!

LikeLike

I drop a leave a response each time I like a article on a website or if I have

something to add to the conversation. Usually it is

a result of the sincerness communicated in the article I read.

And after this article Amy Earhart’s stunning 1944 letter to

Neta Snook | Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last. I was actually moved enough to drop a leave a responsea response 🙂 I actually do have 2 questions for

you if you don’t mind. Could it be just me or do some of these remarks look as if they are left

by brain dead visitors? 😛 And, if you are posting on other

sites, I’d like to keep up with you. Would you make a list the complete

urls of your public pages like your Facebook page, twitter feed, or linkedin profile?

LikeLike