The Amelia Earhart-Mili Atoll connection is well known to those familiar with the work of authors and researchers such as Fred Goerner, Vincent V. Loomis, Bill Prymak and Oliver Knaggs, as well as readers of this blog and Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last.

Much less understood is what transpired between the time of Amelia and Fred Noonan’s pickup at one of Mili’s tiny Endriken Islands in July 1937 and their horrible deaths on Saipan on dates still not precisely known.

In “The Marshall Islands Witnesses” chapter of Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last is a subsection titled “The Kwajalein Connection.” The following is taken from “The Kwajalein Connection,” and was originally published in the February 1996 edition of Prymak’s Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters.

Other compelling stories, unseen in any published books before Truth at Last, will be presented in future posts so that interested readers can connect the dots in the Mili Atoll-to-Saipan logistical scenario.

“ANOTHER GI EXPERIENCE IN THE PACIFIC ISLANDS”

By Ted Burris

In 1965 I was working on Kwajalein, in the Marshall Islands. Having been there since 1964, I knew my job well enough to become a bit bored, and cast about for some volunteer work to absorb time and interest.

As it happened, the Aloha Council, Boy Scouts of America out of Honolulu, was looking for a neighborhood commissioner for the islands. I thought I’d try it.

My primary assignment was to introduce Scouting into the Marshall Islands. Kwajalein already had a couple of troops made up of the children of American families working on the island. So I determined to try to establish the program on Ebeye, three islands north of Kwaj, where most of the Marshallese in that part of the atoll lived.

Organizational meetings required my presence on Ebeye sometimes two or three evenings a week. The meetings were usually concluded by nine or shortly after, but I had to wait until 11 o’clock to get the last boat back to Kwaj. My friend and interpreter, Onisimum Chappelle, tried to keep me entertained until the boat got there.

One evening he mentioned that there was an old man there who had a story to tell. This intrigued me because I was interested in the history of the area.

In the course of our conversation, I asked the old man when was the first time he met Americans? “Before the war.” I was surprised, because I knew the Japanese had closed the Marshall Islands to foreigners in the late ’20s. “I don’t understand,” I said. “How long before the war?” “Five years,” he said.

Ebeye Island is the most populous island of Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands, as well as the center for Marshallese culture in the Ralik Chain of the archipelago. Settled on 80 acres of land, it has a population of more than 15,000.

“How did you meet Americans before the war?” I asked. “Well, I didn’t exactly meet them,” he said. “But I did bring them in.”

“Bring them in? I don’t understand. What happened?”

“A plane landed on the water,” he said. “A big plane.” “Four motors?” I asked. “No, two.” “Where?” I asked again. “Come. I show you,” he said. The old man walked with us from his house to the eastern shore of Ebeye. We went to the south end of the perimeter road. There stood two A-frame houses with a line of four coconut trees. “You see these trees,” he said. “The plane was exactly in line with them.” “How far out?” I asked. “About a hundred yards from the land,” he said.

I should tell you that, at the lowest tides, the reef there is virtually dry. And the Marshallese consider the reef as part of their ’land-holding’ or ’weito.’ In retrospect I was never sure whether the distance was 100 yards from the edge of the island, (i.e. on the edge of the reef), or 100 yards out from the edge of the reef. In the latter case the prevailing currents could have swept the plane south along the reef toward Big Buster before it sank.

“What happened then?” I asked. “Two people got out. A man and a woman,” he said. “The Captain made me take my boat out and pick them up. I didn’t talk to them.”

“The Captain?” I asked. He answered, “The boss, the Japanese officer. The Captain took them away. I never saw them again. He said they were spies.”

It was time to go for the boat back to Kwaj. I thanked the old man and left.

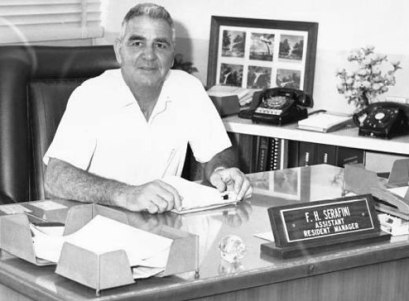

None of this registered with me in particular until a couple of years later when I had moved to another assignment on Roi Namur. The Island Manager there was Frank Serafini. He, too, was something of a history buff. Frank and I had many pleasant chats about the history of the islands. In one of these I mentioned the story the old man had told me.

“So that’s where it came down!” he exclaimed. “That answers it!”

“Answers what?” I said.

“Let me tell you a few things.” Frank went to his desk and took out a letter. “This is from Navy Commander so-and-so.” (I don’t remember the name.) “I’ve been corresponding with him for years.”

“Who was he?” I asked.

“He was with Navy Intelligence dining the war, and he was attached to the 4th Marines when they invaded Roi-Namur. He went in with the first wave on Roi. His specific task was to look for any evidence that Amelia Earhart or her navigator, Fred Noonan, had been there!”

“Why here?” I asked. “Because Roi had the only airfield on the atoll at that time,” Frank said. “If the Japs were going to take them anyplace from Kwajalein Atoll, they had to come through here!”

“Did he find anything?”

“Here, read this letter. Starting here.” He pointed to a place on the second page. “I was rummaging through a pile of debris in a comer of the burned-out main hanger,” the writer said, “when I came across a blue leatherette map case. It was empty. But it had the letters AE embossed on it in gold leaf! They were here all right!”

“That’s enough,” Frank said. He took the letter back, and that’s the last I saw of it. “What did the Commander do with the map case?” I asked. “He said he turned it over to Naval Intelligence. He doesn’t know what happened to it after that,” said Frank.

“Does anybody know about this? Why would they keep such a thing secret?” I wanted to know. “Because even now the Navy doesn’t want to admit they had anything to do with spying against the Japanese before the war,” Frank said.

Frank eventually left Roi and went to Saudi Arabia on another project. He and his wife moved to Sun City, Ariz., and may still be there. He also may still have his correspondence from the Commander.

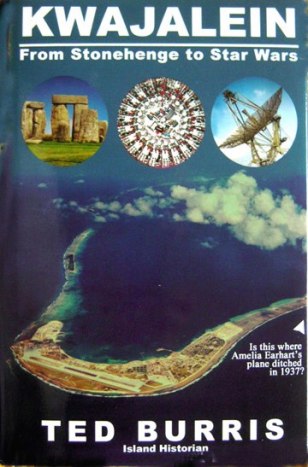

In Kwajalein: From Stonehenge to Star Wars, Ted Burris self-published 2004 book, he poses this question on the cover: “Is this where Amelia Earhart’s plane ditched in 1937?” The answer is almost certainly negative, but Burris’ account suggests a more complex scenario involving the presence of Amelia Earhart and Fred Goerner at Kwajalein Atoll.

I went back to Ebeye to find the old man, but I was told that he had gone back to Likiep, his birthplace, to die. I had wanted to ask him about his “five years before the war” comment. Then it hit me. The old man probably counted the war as starting when the U.S. made their first carrier strike against Kwajalein in late 1942.

I tried to talk the Army into using their recovery submarine to look around the reef; they told me they wouldn’t touch that situation with a ten-foot pole, and I should forget it. But — I never have. (End of Ted Burris account.)

The empty “leatherette map case” with the “letters AE embossed on it in gold leaf” reported by the unnamed Navy commander is strangely similar to a “locked diary engraved 10-Year Diary of Amelia Earhart,” discovered by former Marine W.B. Jackson on Namur Island in 1944. Jackson reported his experience to Fred Goerner in 1964, and Goerner presented it in his 1966 bestseller, The Search for Amelia Earhart. Were these different descriptions of the same item?

And what about the twin-engine plane that “landed on the water . . . about a hundred yards from the land,” as the old man told Ted Burris? Was it Amelia Earhart’s Electra, or an altogether different aircraft? We’ll try to answer this question in future posts.

I was unable to locate Burris, but the Roi-Namur Links page of the The Kwajalein Community Web Site, an impressive local history collection created by local personality Shermie Wiehe offers additional information about Frank H. Serafini, Roi-Namur assistant resident manager during the 1960s and ’70s.

“Frank was well known for making Roi-Namur beautiful by planting 100s of coconut trees,” Shermie wrote. “He was highly respected by the Roi-Rats for his excellent management of island life and not forgetting ‘Shermie & Friends Band‘ was treated very good by Frank’s Staff during our trips to entertain the Roi-Rats. Some of the best memories of performing was at Roi-Namur. Thanks Frank! Roi-Namur will never be the same. The days you were managing were the best!”

On the same page, Serafini’s son, Frank B. Serafini, a Shell official living in Egypt, recalled that his father was living in San Antonio, Texas, was in good health at 97, and though he didn’t hear well or use a computer, was otherwise “just the same ol’ guy he always was.”

In a recent email to me, Frank said his father will be 100 in December 2015, and though most of his friends are gone, “It is always a pleasure to hear from anyone who can recall his passion for work on the islands he so deeply cared for. Us people from the Pacific have an ingrained fascination for the Earhart story.”

I hope others who lived and worked on Kwajalein, where the captured Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan were undoubtedly taken by the Japanese military in 1937 on their way to their miserable fates on Saipan, will help keep the truth alive, regardless of its continuing status as a sacred cow, not only in Washington but throughout the U.S. media establishment.

![Fishing boat story 5 This story appeared at the top of page 1 in the July 13, 1937 edition of the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania)-Globe Times. “Vague and unconfirmed rumors that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan have been rescued by a Japanese fishing boat without a radio,” the report began, “and therefore unable to make any report, found no verification here today, but plunged Tokio [sic] into a fever of excitement.” The story was quickly squelched in Japan, and no follow-up was done. (Courtesy Woody Peard.)](https://i0.wp.com/earharttruth.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/fishing-boat-story-5.png?w=616&h=352&ssl=1)

As usual, Mike – another hit out of the ball park with this information. How interesting that several people alive in 1937 claim to have seen a small plane go down – in more than a couple of locations – and the fliers taken by Japanese military. I wonder if some of these witnesses – after so many, many years – are unclear about which island they were on when they saw what they describe? Or are some reporting what they heard from others?

I can understand why some of AE’s personal items might be found on Kwajalein, since they did make a stop there on the way to Saipan. I imagine everything on the Electra was on that ship. Easy to think 1-2 items might be slyly pocketed (a la Sandy Berger …) and taken off the ship, shown around to cronies, and then fear of punishment would persuade the thief to destroy or hide the item(s).

Thanks for this luscious tidbit!

LikeLike

Once again, Mike enlightens & educates us with more eyewitnesses testimony, of Amelia Earhart’s presence on the remote island of Kwajalein. Certainly she would have been greeted as a *GUEST by natives, but not by the Japanese as we all know.

Isn’t it AMAZING how *memorials, *shrines, statues & *tributes are paid to all those who died on Pearl Harbor and yet there is NOTHING acknowledged by the U.S. of Amelia Earhart’s PRESENCE & DEATH on Saipan??

We have FDR to THANK for this don’t we?? Let’s BURN, BULLDOZED and BURY FDR’S house, cars, books and tell everyone that he simply d i s a p p e a r e d somewhere in the HUDSON RIVER………

LikeLike

The plane was a Japanese seaplane; it didn’t sink, just brought both flyers to the island hdq.

Tamaki Myazo was aboard the fishing-boat that ‘rescued’ AE & FN from Barr Is. if you need a name! He was not the captain that Elieu J. knew, only a mate.

LikeLike

I just received my purchased book by Burris and after scanning it over and trying to find mention of Earhart, he refers to people by their first name and the first letter of their last name. He calls Frank Serafini as Frank S! All throughout the book he does this. Drives me crazy. Why can’t he give their full name? There is no Index in the back of the book and on the inside top is a Parkinsonism scribble “9 Jan 2009 Pam…I hope you enjoy reading this as much as I enjoyed writing it…Ted Burris”.

This was suppose to be a new book, not one returned by a previous owner. The sea stories are essentially rants from his time there. Maybe I sound cruel, but this book is getting returned. Brundage Publishing in Binghampton NY should have assembled an index and edited it. Burris was in Pine Valley, NY in August 2004. Not sure he is still alive.

On the back cover of this 314 page book, it says, referring to Burris, “He interviews a native who probably witnessed Amelia Earhart landing in the water and being captured by the Japanese” and I wonder if this statement, along with the front cover “Is this where Amelia Earhart’s plane ditched” was to sell more books.

LikeLike

Mike,

You should have checked with me before you bought this book. Its Amazon rank is over 4 million, which means about 2 people have bought this book in its entire history! The Burris information in TAL is from the AES Newsletters. All the rest is flotsam. Good luck getting your money back!

MC

LikeLike