Today we continue with Part II and the conclusion of John Riley Jr.’s “The Earhart Tragedy: Old Mystery, New Hypothesis,” from the August 2000 issue of Naval History Magazine. Although Riley was a thoroughgoing crashed-and-sanker and Navy apologist, and there’s nothing new in his conclusions or the evidence he presents, you won’t see Riley’s depth of research and detail in today’s Earhart disinformation screeds. Little more than an iPhone and a third-grade reading level are required now for our “woke” citizens — and growing illegal citizenship as well — to become the latest brainwashed tools of the Deep-State, and in many far-more live-threatening topics than the Earhart disappearance.

Exaggerated Search Reports

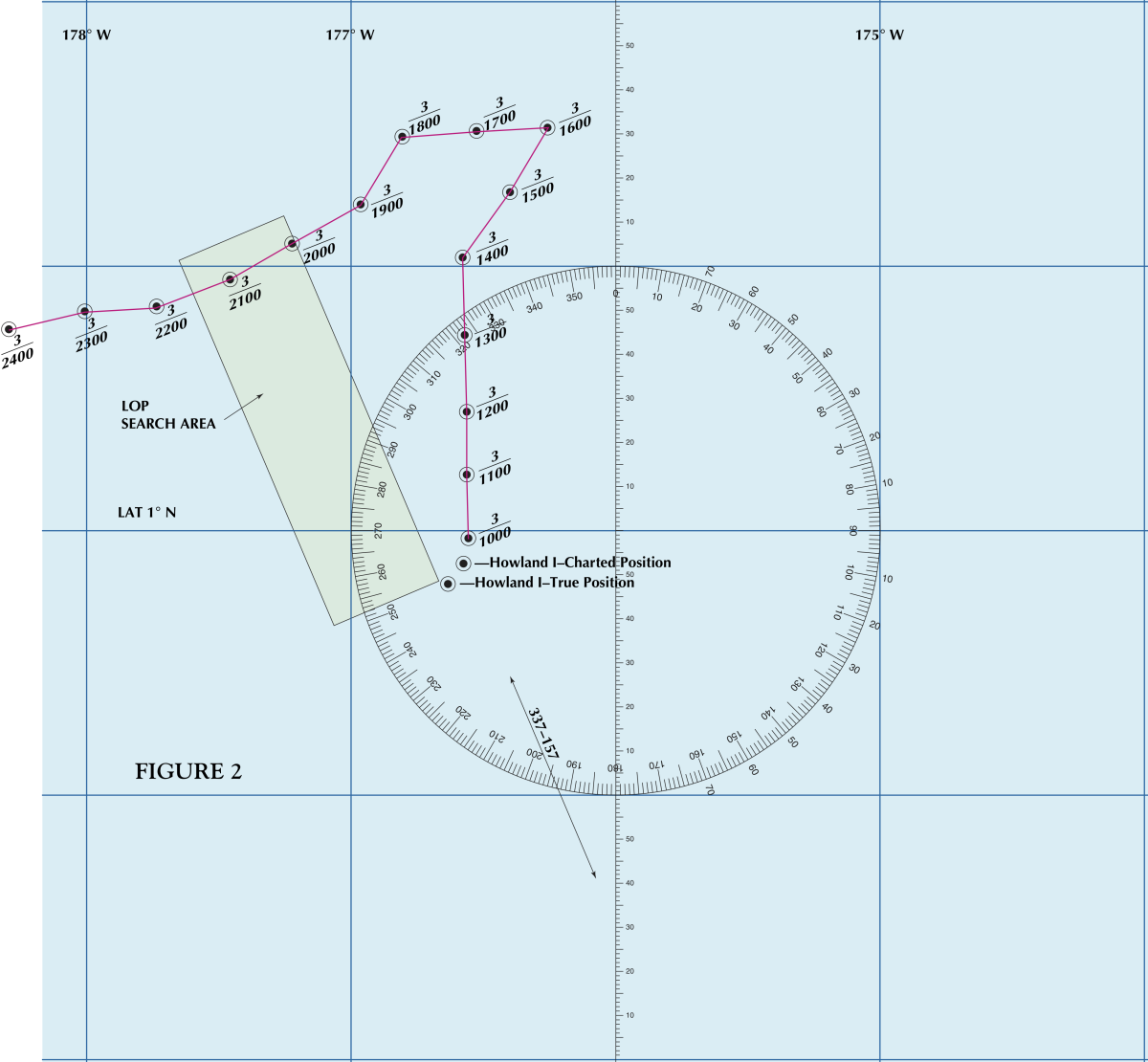

In his 6003-1250 message of 3 July, Thompson claimed to have searched “3,000 square miles.” His deck log shows he steamed 268 miles. Therefore, he made the assumption that he could at all times see a plane on the water at a distance of up to 5.6 miles on either side of his course. But the cutter covered only about 124 miles during daylight—and only about 55 of them on or within 10 miles of the LOP. Most of the night he was on random courses far to the east of the LOP search area and could see practically nothing in the darkness—except the meteors that he mistook for flares. A more accurate report would have claimed only 616 square miles searched. He completely misled headquarters.

In a later message, Thompson claimed to have “searched 1,500 square miles during the night.” This concept of searching is hard to accept. It seems to assume that the downed fliers would still be alert, be able to see the ship’s searchlight, and be able to launch flares to attract attention. A partly submerged plane, miles away, could not easily be seen at night, with or without the “vigilant lookouts [and] and powerful searchlights” mentioned in his messages.

For years, many details of the search for the missing fliers were classified. They were declassified finally and released as required under the Freedom of Information Act, but the picture remains obscured today, perhaps unintentionally, by a pea soup fog of disinformation that continues to mislead researchers.

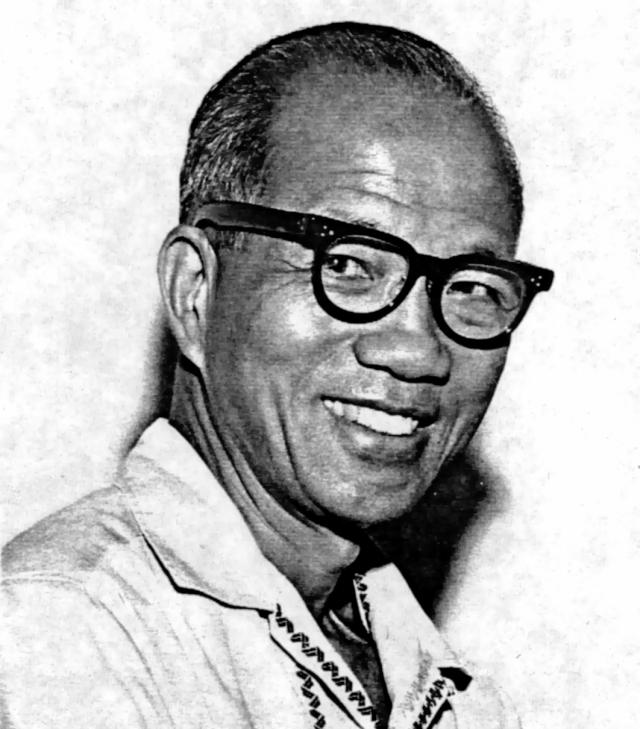

It is interesting to speculate on what person(s) may have written one of the strangest documents that survives from that era: the Howland radio log. Today, it is virtually impossible to determine who concocted it; in any event, this record of the DF station on Howland Island is a counterfeit, according to the two men still alive who were on the island at the time and are alleged to have participated in writing it: Yau Fai Lum and Ah Kin Leong (see below). The Itasca’s deck logs, radio logs, message traffic and Commander Thompson’s Earhart Search Report (of which at least two versions exist), however, all support the fiction of a radio and DF watch on Howland during the Itasca’s search for the fliers. If the Howland radio log is bogus, it follows that these other fundamental documents also may be suspect in some details.

If this sound like classic “conspiracy theory,” remember that all material was classified promptly and researchers like Commander Weems and Paul Mantz were denied access—and access for all researchers continued to be denied for many years. Francis X. Holbrook, who wrote “Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight”(Naval Institute Proceedings, February 1971, pages 48-55), concluded that he had been led astray and put to considerable trouble by misinformation. Such misinformation did not require a large conspiracy; indeed, a single mischief maker could have been responsible. In the absence of access to factual data, researchers were at the mercy of whatever tidbits of information—or misinformation—that were leaked to them. I put my trust in the following accounts of Lum and Leong, both of whom maintain that the log was cooked.

In the mid-1930s, both the United States and Great Britain claimed the Line Islands, which included Jarvis, Baker and Howland. Thinking they might one day prove to be of strategic value, the United States occupied them in 1935 to reinforce its claim. Four-man civilian teams were landed on each and rotated from time to time; all were trained as weather observers, and each team included one amateur radio operator. They sent daily weather reports to another amateur radio station in Honolulu, which passed them to Pan American Airways, then pioneering trans-Pacific clipper flights.

I began a long and interesting correspondence with Lum.2He told me of that fateful day when they waited in vain for Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan. I was impressed by his almost total recall of details. Lum said he had washed his sheets and aired his bed, the best on the island, so that Amelia could lie down and rest in comfort after her long, exhausting flight. He described the private shower improvised for her—a 50-gallon drum of fresh water with canvas enclosure.

When I asked Lum about Cipriani and the high-frequency DF equipment, he replied: “I never met him.”

“How could you not meet him?” I asked. “Didn’t you, Henry Lau, and Ah Kin Leong live with him on that fly-speck island that had only one sleeping shelter and one 15-foot-long tent for a kitchen/dining area? And didn’t you report to him and stand radio watches under his direction during the 16 days that the Itasca was at sea searching for Amelia?” I enclosed a copy of the Howland Radio Log, which had numerous entries supposedly made by Lum.

He wrote back immediately:

He also pointed out that his name in the log was consistently spelled wrong (as “Yat” Fai Lum) where he supposedly signed off at the end of each watch. Yat is a common Chinese name, but his is “Yau” not “Yat.” He added, “I should know how to spell my own name. According to the Howland log,” he continued, “other operators were Henry Lau, [call letters] K6GAS, and Ah Kin Leong, K6ODC. But they were not even on the island during the 16-day search. They and Cipriani were on board the Itasca.”

Henry Lau is dead, but I wrote to Ah Kin Leong, ex-K6ODC. Asked what he knew of all this, he replied on 4 September 1994: “No idea who wrote the false log. I stand no radio watch on Howland Island. Cipriani, Henry Lau and me was on the Coast Guard Cutter Itasca when it left Howland Island looking for Earhart.” (According to the Itasca’s deck log for 2 July, when it became evident that Earhart was overdue and in trouble, the landing party [no exceptions are mentioned] returned to the cutter, which departed to begin a 16-day search for the missing fliers. It does not say that Cipriani or other radio operators remained ashore. The 18 July deck log entry, however, states that they re-boarded from Howland on that date.)

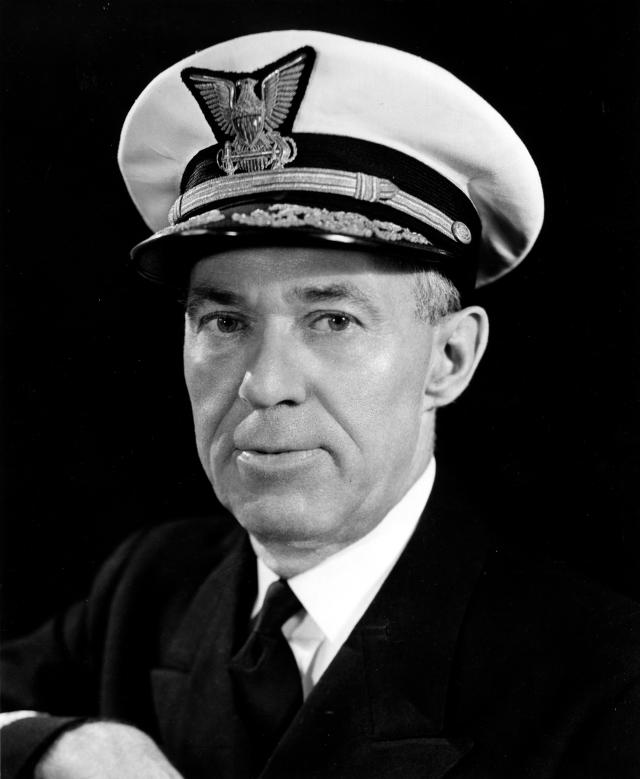

Coast Guard Chief Radioman Leo Bellarts led the radio teal aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Itasca Itasca during the final flight of Amelia Earhart.

On 4 July, the Commander Hawaiian Sector had sent the following message to the Itasca: “HAVE HOWLAND DIRECTION FINDER BE ON STANDBY FOR BEARINGS.” Thompson would have been hard put to explain that he could not comply because he had Cipriani on board. So, inserted in the cutter’s log dated 4 July, is this message supposedly sent to K6GNW (Lum’s call letters) on Howland as follows: “MR. BLACK SEZ CIPRIANI IS IN CONTROL ES TO KEEP CONTINUOUS WATCH ON 3105 ES TAKE BEARINGS USE CHINESE OPS HR IF YOU HAVE TROUBLE HAVING BOYS STAND WATCHES MR. BLACK SEZ TO TELL JIMMY.”When I asked Lum about this, he replied: “It is all B.S.”

Was “HR” a Freudian slip or just a careless error? It means “here,” not “there,” as intended. If Cipriani really had remained on Howland when the landing party was recalled, it seems logical that such a message would have been sent to NRUI2, the call letters he used with the portable radio equipment that he took ashore along with the portable direction finder. It is very unlikely that such a message would have been sent to K6GNW (Lum’s station) instead.

Circumstantial details, such as the misspelling of Lum’s name, support Lum’s and Leong’s statements. The log also incorporates a one-day date error in all entries (a day must be subtracted to get the correct date), and uses a +10 1/2 time zone instead of +11 1/2. It seems quite unlikely that an error of one whole day would persist in a radio log, day after day, if it were kept by four operators as claimed. Surely, at least one of them would have known the correct date. Furthermore, the first page of the bogus log is headed “Radio log ITASCA,” at least in the version that I have. That looks like another Freudian slip by someone assigned to the Itasca—or whoever actually wrote the log while on board the Itasca instead of on Howland.

Why would Thompson take Cipriani off Howland Island when the cutter departed on the search? He did not want him there in the first place, but he probably was not thinking about Cipriani at all when he ordered the landing party back to the ship.

To sound plausible, the log had to be written by a person with detailed knowledge of what was going on at the time, and who was familiar with the usual log details, radio procedure signs, and jargon—i.e. a radio operator.

Chief Radioman L. G. Bellarts had died, and I contacted his son to ask what papers and memoirs his father left. Bellarts, I was told, recognized the historical importance of the radio logs and took personal possession of them soon after the plane was lost. He guarded them carefully for years, but eventually sent them to the National Archives. I wrote asking whether the logs they were giving researchers were direct copies of those received from Bellarts, or had they come perhaps from some other source? To date, I have received no reply.

I have been unable to locate Frank Cipriani or any close relative. Dwight Long, another Earhart researcher, told me that Cipriani became a civilian radio operator and was lost at sea in a World War II convoy when his ship was torpedoed.

A retired officer who signed the Itasca’s deck log as “W. I. Swanston, Lt. (j.g.) USCG, Navigator,” confirmed being in the ship’s company during the search for the fliers but denied having been the navigator, despite clear evidence to the contrary. He was 86 when I contacted him. When I pointed out that he had definitely signed the Itasca’s deck log as navigator, I got a rude answer. I asked him a question concerning navigation on board the cutter and he again replied rudely that I did not know anything about navigation. He did not seem to understand the point I was trying to make. He seemed to be in a bad mood. I think that he had long ago forgotten any details concerned with navigation and did not want to be associated in any way with the incident.

![Fishing boat story 5 This story appeared at the top of page 1 in the July 13, 1937 edition of the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania)-Globe Times. “Vague and unconfirmed rumors that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan have been rescued by a Japanese fishing boat without a radio,” the report began, “and therefore unable to make any report, found no verification here today, but plunged Tokio [sic] into a fever of excitement.” The story was quickly squelched in Japan, and no follow-up was done. (Courtesy Woody Peard.)](https://earharttruth.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/fishing-boat-story-5.png?w=616&resize=616%2C352#038;h=352)

Recent Comments