Goerner’s “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart” Conclusion

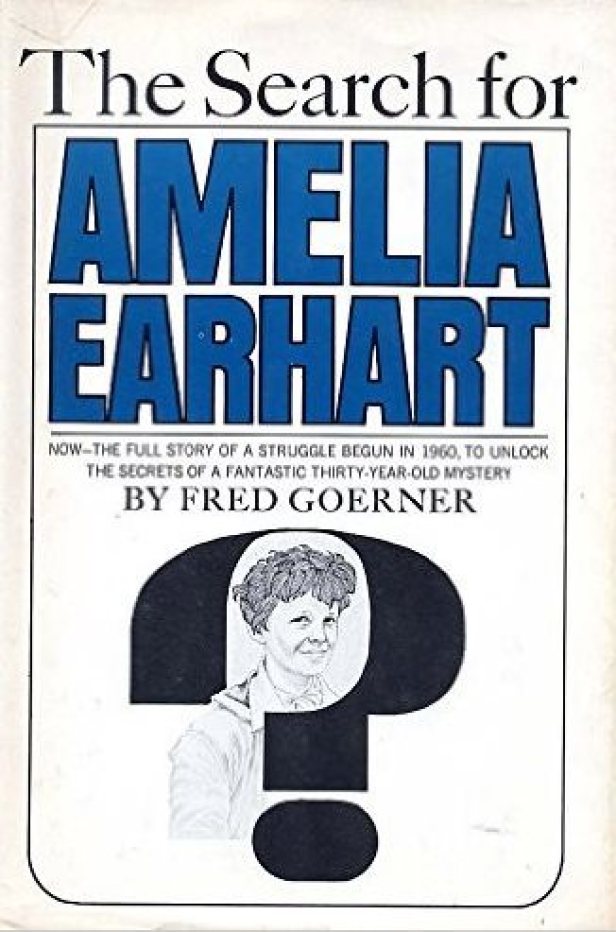

Today we conclude Fred Goerner’s 1964 Argosy magazine feature story, “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart.” When we left Part III, former Navy men Eugene Bogan and Charles Toole had contacted Goerner and shared their mutual wartime experiences in the Marshall Islands that pointed to Amelia Earhart’s presence there, launching Goerner’s Marshalls investigations, which were far briefer and less productive than his Saipan research.

We open the final part of “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart” as Goerner is contacted by another World War II veteran, this one from Saipan, who has some fascinating information to share:

Ralph R. Kanna, of Johnson City, New York, has worked seventeen years in a responsible position for the New York Telephone Company. In 1944, Kanna was sergeant of the Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon, Headquarters Company, 106th Infantry, 27th Division, during the assault on Saipan. Kanna’s duty was to take as many prisoners as possible for interrogation purposes.

“On Saipan, we captured one particular prisoner near an area designated as ‘Tank Valley,’ ” wrote Kanna. “This prisoner had in his possession a picture showing the late Amelia Earhart standing near Japanese aircraft on an airfield. Assuming the picture of the aircraft to be of value, it was forwarded through channels to the S-2 intelligence officer. But more important, on questioning of this prisoner by one of our Nisei interpreters, he stated that this woman was taken prisoner along with a male companion, and subsequently, he felt both of them had been executed. From time to time, I have told these facts to associates, who finally have convinced me to write.”

Kanna went on to list three Nisei interpreters who served with his unit during that period: Richard Moritsugu, William Nuno and Roy Higashi.

Joining Ralph Kanna and Robert Kinley, who claimed to have found photos of Amelia Earhart on Saipan, was Seabee Joseph Garofalo, pictured here on Saipan in July 1944. While assigned to Naval Construction Battalion 121 during the invasion, Garofalo found a sepia photo of Amelia Earhart inside the wallet of a dead Japanese officer. He lost the photo on Tinian several weeks later. Garofalo, the founder and curator of the Bronx Veterans Museum, passed away in March 2016 at age 95. (Courtesy Joseph Garofalo.)

I have located and spoken personally with both Moritsugu and Nuno. Moritsugu, now living near Honolulu, is unwilling to discuss his part in the Saipan invasion. Nuno lives in Pasadena, California, and indicates that he was not with Kanna that day in 1944. I found Roy Higashi just three days ago. He is living in Seattle, Washington, and almost seemed to be expecting my call. He said he had something to tell me, but would rather do it in person. Higashi is bringing his family to San Francisco on vacation, and will contact me on arrival. I’m sorry I cannot include his information in this article because of the publication deadline.

Robert Kinley of Norfolk, Virginia, was a demolition man with the Second Marine Division. Pushing inland from Red Beach One, his squad came upon a house near a small cemetery. Kinley went inside to clear it of any booby traps. On a wall, he found “a picture of Miss Earhart and a Japanese officer. The picture was made in an open field, showing only a background of hills. The officer wore a fatigue cap with one star in the center.” Kinley says he took the picture with him, but everything was lost in July 1944, when he was wounded.

Robert Kinley then added a bit of provocative information. “The Japanese had a command post in a tunnel next to the house where I found the picture. My demolition team closed up the tunnel. You might be able to find more pictures or records in the tunnel.”

Kinley sent along a map showing the location of the house, tunnel and graveyard. It coincides almost perfectly with the area Devine was shown by the Okinawan woman.

In September 1962, I went back to Saipan for the third time, but I had to do it on my own time and money. KCBS wasn’t uninterested, but there’s a limit to financial soundness in making assignments. I couldn’t drop it, though; there was just too much to go on, and no one in official places had been able to satisfactorily answer any of the many questions raised by the investigation.

Fearing that I might have become prejudiced, I took along Ross Game, the editor of the Napa (California) Register, consulting editor to the nineteen Scripts newspapers in the West and Secretary for the Associated Press on the Pacific Coast. We picked up Captain Joe Quintanilla, Chief of Police of Guam, and his detective-lieutenant, Edward Camacho, and took them along, too.

In this September 1962 photo, California newspaperman Ross Game, who accompanied Fred Goerner during a few of his early 1960s investigations, including one on Saipan, is flanked on Saipan by Guam Detective Edward Camacho (left), and Capt. Jose Quintanilla, Guam Police Chief.

Things had changed in one year. My, had they changed! Commander Bridwell was gone; the Navy was gone; Mr. Schmitz was gone – and NTTU was gone. I should say NTTU were gone, since there were eleven of them.

The fence gates were open, and we went in. Commander Bridwell and the Naval Administration Unit had been a front for one of the most elaborate spy schools in the history of this or perhaps any country. The faculty consisted of civilian professors of espionage, the very same men whom I had addressed that night at the club. It’s hard to imagine the impact of coming out of the jungle and discovering a modern town of ninety two- and three-bedroom houses with concrete roofs, typhoon-proof and modern in every respect even to modern landscaping; a modern apartment house for the single members of the faculty; a library, snack bar, barber shop and theater-auditorium. Seven of the NTTU training facilities were located on the north end of the island and four on the east. For the spy-school student, there were sturdy, concrete barracks at each site and other concrete buildings in which classes were held.

For ten years, the students were flown into Kagman Field at night, taken in buses with the shades drawn to any of the eleven areas, trained in techniques of spying and a very specialized brand of guerrilla jungle warfare. Most of them never knew where it was they were being trained. When their courses were completed, they were dispatched on any one of a thousand missions, penetrating through or parachuting behind Communist lines. Nationalist Chinese, Vietnamese, and men from other areas were brought to Saipan, trained and then assigned.

Where did the NTTU go? Why did they go?

I can’t answer the first. I don’t know that I want to.

The second has to do with the focus of international attention the Earhart story placed on Saipan twice within two years, but more importantly, the United Nations inspection team for the Trust Territory of the Pacific gave Commander Bridwell and the Navy bad marks in 1961 for the administration of Saipan. They had done too much rather than too little for the people of Saipan. It was out of line with what the Department of Interior was doing for the rest of the people of the Pacific area. I don’t believe the UN team even knew about the NTTU. They probably got the same trip to Bridwell’s quarters I did. In any case, when the history of the post-World War II struggle between East and West is finally written, I’m sure Saipan and NTTU will be prominently mentioned.

Saipan’s Kagman Airfield, also known as East Field, fall 1944. Among the aircraft are Consolidated B-24 Liberators from the 819th Bomb Squadron, of the 30th Bomb Group, C-47 Skytrains and, in the distance, a B-29 Superfortress. Bruce M. Petty, author of Saipan: Oral Histories of the Pacific War (2009), wrote, “The CIA had a secret base on the north end of Saipan in the 1950s and early 1960s where they trained Chinese Nationalists to fight Chinese Communists. Kagman field was used to fly in trainees at night were they were bussed to their quarters at the north end of the island. The building still survive are currently being used by the CNMI government. We lived in one for four years.”

We did some more excavation around the perimeter of the cemetery; this time outside the northern end, but found nothing. We needed Devine to show us the spot, but permission was still being denied to him. We did find where the house Kinley had entered once stood, and we found a huge mound which must be the command post he speaks of. It would be, of course, a major and expensive earth-moving job to open it up.

Ross Game, Captain Quintanilla, Eddie Camacho, Father Sylvan and I went back over every piece of testimony, and even managed to turn up some new leads. The consensus: They were more convinced than I. Two American flyers, a man and a woman, bearing an almost unmistakable resemblance to Earhart and Noonan had indeed been brought to Saipan by the Japanese in 1937.

The most important event of the third expedition came one morning at the mission house. One Jesus De Leon Guerrero, a native Saipanese, came to see me. Father Sylvan served as interpreter. Guerrero proposed a trade. He had been collecting scrap from the war for years and had a mountainous pile. If I would arrange a Japanese ship to come to Saipan to pick up his scrap, he would give me the conclusive answer to the mystery of the two American flyers.

I remembered several Navy and Department of the Interior people telling me that U.S. policy was that no Japanese ships were permitted to enter the former mandated islands.

I couldn’t have changed that policy if I had wanted to, which I didn’t. No story can be bought without being tainted. I told Guerrero, through Father Sylvan, that if he had anything to say to me, he’d better say it now. There would be no deal. Guerrero blinked, turned on his heel and walked out of the mission. The most striking thing about the whole conversation was that I recognized Guerrero. He was the native who had been in my Quonset that rainy night the year before. Father Sylvan told me later that the rest of the natives fear Guerrero. Before and during the war, Guerrero worked with the Japanese military police.

The trip in ’62 produced another vital piece of information. Ross and I went down into the Marshall Islands, and found Elieu [Jibambam]. Elieu teaches at the Trust Territory school at Majuro. He tells exactly the same story he told to Bogan and Toole in ’44. The American flyers landed near Ailinglaplap in 1937.

Elieu Jibambam, one of the earliest known Marshall Island witnesses, though not an eyewitness, told several Navy men on Majuro in 1944 about the story he had heard from Ajima, a Japanese trader, about the Marshalls landing of the white woman flier who ran out of gas and landed between Jaluit and Ailinglapalap.” Elieu’s account was presented in several books including Fred Goerner’s Search. This photo is taken from Oliver Knaggs’ 1981 book, Amelia Earhart: her final flight.

And now, as you read this, I’ll once more be on Saipan. There is one important difference this time. Thomas Devine is with me. After nearly a four-year effort, permission has finally been granted for him to enter the island.

Why has such an effort been necessary? What about Japan? This long after the war, wouldn’t she be willing to admit an incident involving two white flyers?

The answer is no. It involves far more than the detention of Earhart and Noonan. Japan has categorically denied building military facilities in the mandated islands prior to Pearl Harbor. In the war crimes trials in Tokyo in 1946 and ’47, Japan stated, “The airfields and fortifications in the mandated islands were for cultural purposes and for aiding fishermen to locate schools of fish.” It is obvious that Japan cannot admit an incident involving two American flyers before the war without also admitting a far graver sin – the necessity for covering up their activities in the mandates. If Japan ever concedes that the islands were used for military purposes, it will represent a violation of the League of Nations Mandate, a breach of international law, a most serious loss of face and the loss of the last chance to get the islands back.

Is there any other way to clear up the mystery, through extant records perhaps?

I don’t know. The records that might shed light upon this matter seem beyond our reach. According to the United States Navy, Army and other departments of the Government, the following have been declared “missing, destroyed, or returned to Japan”:

- Twenty-two tons of Japanese records captured on Saipan, which were never interpreted.

- The radio logs of Commander Bridwell’s four United states logistics vessels.

- Records of a physical examination of both Earhart and Noonan, including dental charts made by Navy Chief Pharmacist Mate Harry S. George, in Alameda, in the year 1937.

- The large bulk of Naval intelligence records for the Pacific from 1937 to 1941.

In spite of the fact that the Navy sent the carrier [USS] Lexington to Howland Island in 1937 and spent some $4,000,000 in a fruitless search, their official position today, at least to CBS and the Scripps’ League newspapers, is that “the Earhart-Noonan disappearance is a civilian matter. There has been and is no reason for this Department to make an investigation.”

Bridwell told me an ONI man conducted an investigation in 1960 after my first visit, and the testimony could not be shaken. The Navy maintains there has been no investigation at all. As recently as four months ago, Captain James Dowdell, now Deputy Chief of Naval Information in Washington, vehemently denied to Ross Game that the Navy was withholding any information, and indicated that the Navy hadn’t conducted any investigation. Yet, just two months ago, the U.S. State Department stated in a letter to me, “The State Department does have a limited amount of information about the Earhart matter which is Classified, but the Navy Department has informed us that they conducted a complete investigation in 1960, and there’s nothing to the conjecture that Earhart and Noonan met their end on Saipan.”

(Editor’s note: Goerner was shown part or all of the then-classified 1960 ONI report in April 1963, and he commented briefly on its contents on pages 236 and 307 of The Search for Amelia Earhart, First Edition. Based on the publication date (January 1964) of this article, he clearly had seen the classified report in plenty of time to mention it here. Why he didn’t disclose this fact in this article is unknown to this observer.)

Just before The Search for Amelia Earhart was published in November 1966, True (The Man’s Magazine) ran a lengthy preview, extracting passages directly from the book. True also ran this photo, of Thomas E. Devine, who finally made it to Saipan in December 1963, with Goerner, (seated right) and missionary priests Father Sylvan Conover (smoking pipe) and Father San Augustin, preparing to search for the gravesite Devine was shown by an unidentified Okinawan woman on Saipan in 1945.

As I said earlier in this article, I can’t really blame the Navy Department for its evasiveness. The Navy was fronting, at any cost, for the CIA, and it’s going to be a wee bit embarrassing, at the very least, to clear the record now.

Were Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan on a spy mission in 1937? I simply haven’t the space to begin that discussion here. Let me simply say that those “two American fliers” on Saipan are I believe, the key to an even more incredible story: The twenty years in the Pacific before Pearl Harbor and the bitter battle between departments of our Government over what to do about the Japanese mandated islands.

There are many who say that the enigma of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan is best left untold. “Embarrassment of Japan at this time would not be wise,” they say. “What good can it do to rake over old coals?”

My answer is a simple one. With most Americans, the individual still counts. Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan fought a battle for most of their lives against the sea and the elements, not against men bent on war. We orbit men around our earth and turn our eyes to the stars and what may lie beyond because of the courage and contribution of such as Earhart and Noonan.

If they won their greatest victory only to become the first casualties of World War II, the world should know. Honor for them is long overdue.

When all is considered, a single question remains: If the two white flyers on Saipan before the war were not Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan, who were they?

Within the next few days, we may know the answer. (End of “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart.”)

Readers should note that this article well summarized the state of Goerner’s Earhart research in late 1963, before his fourth trip to Saipan in December 1963. Some of Goerner’s most important findings and ideas would undergo radical changes in the coming years, and long before his death in 1994, he would actually renounce his belief in Earhart’s Mili Atoll landing. In future posts I will endeavor to flesh out as much of these small mysteries as I can.

Fred Goerner’s “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart” Part III

Today we move along to Part III of Fred Goerner’s January 1964 Argosy magazine opus, “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart.” When we left Part II, Goerner and missionary priest Father Sylvan Conover were trying to locate the gravesite of “two white people, a man and a woman, who had come [from the sky] before the war” that an otherwise unidentified Okinawan woman had shown to Thomas E. Devine in August 1945, and which Devine later wrote about extensively in his 1987 classic, Eyewitness: The Amelia Earhart Incident.

We continue with Part III of “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart”:

Father Sylvan and I matched the photograph to the terrain as best we could, and one of the natives showed us where a small dirt train had run past the southern boundary of the cemetery. Pacing off “thirty to forty feet to the left,” we arrived in a grove of trees, and with a crew of eight Carolinian natives, excavation began. We went to a depth of six feet among the trees, and then moved slowly to the west. About one o’clock, the afternoon of September twenty-first, Commander Bridwell, who had been watching the proceedings, let out a shout and brushed the natives back from a newly opened area.

Dozens of pieces of skull and many teeth were visible at both ends of a shallow grave not more than two feet in depth. Large teeth were found at one end, smaller ones at the other – indication that at least two individuals, perhaps a man and a woman, had been buried head to foot. As quickly as Bridwell had moved, several shovelfuls had been thrown aside, so, for the next four days, we sifted every bit of earth for a dozen feet around. Seven pounds of bones and thirty-seven teeth were recovered. The island’s doctors inspected the remains, and generally agreed that the grave had been occupied by a man and a woman. The dentists felt there was a strong possibility that the people had been Caucasians, as some of the teeth appeared to contain zinc-oxide fillings; the Japanese had never used that material.

Cutline from The Search for Amelia Earhart: “Father Sylvan Conover at grave site outside Liyang cemetery where remains were found in September 1961. The cross and stones were placed here by natives after the site had been excavated. Author’s Photo. (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

The afternoon the excavation was completed, we carefully wrapped the remains in cotton, and Father Sylvan placed the package in the church vault.

That night came the strangest experience of my life. I was staying in what was laughingly referred to as the “Presidential Suite.” It was nothing more than a Quonset hut, about twenty-five yards above the commander’s quarters. I don’t know what awakened me. It was about two o’clock in the morning and it was raining quite hard outside. As I sat bolt-upright on the cot, there was a flash of lightning, and I saw a man in the room by the door. I jumped from the cot and yelled at him, “What do you want?”

As he turned, I saw he had a machete in his hand. He stared at me for a second, then ran out through the front of the hut, banging the screen door behind him. I pursued him to the door, and in the glare of the running light on the front of the hut, I got a good look at him as he raced across the asphalt road and plunged into the jungle. He was a native – a man I was to hear a lot more from later.

As I tried to figure out what had happened, I was shaking so badly I could hardly light a cigarette.

“Were you really awake? Did you really see the man, or did you dream it?” I questioned myself. Wet sandal marks around the room leading from the door answered my question.

“What did he want?” was the next logical challenge. Certainly not my life. If he had wanted, he could have killed me as I lay on the cot. Expensive motion picture and still cameras and tape-recording equipment rested on the cot next to me. Several hundred dollars in cash was exposed on top of the bureau next to my passport. Nothing had been taken. Nothing had been disturbed. Nearly a year was to pass before the realization came as to what my visitor sought: The package of human remains I had given to Father Sylvan for safe-keeping.

The next day, I asked Bridwell for permission to take the package to an anthropologist in the States for study. He didn’t want the responsibility, and cabled Washington for clearance.

That night, as we waited for Washington’s answer, I received a mysterious summons by phone from a man named Schmitz. I was to be admitted to the NTTU area for the purpose of addressing their personnel on the subject of Amelia Earhart. A civilian in a handsome new car picked me up at my Quonset, drove me by circuitous route through the jungle, up a hill and deposited me in front of a night club! I mean a night club – complete with canopy leading from the road, dance floor, bar and stainless steel kitchen.

From Search: “Interior of NTTU Club where author addressed CIA training staff in Saipan, 1962.” Author’s Photo. (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

Mr. Schmitz (I never learned his full name) met me at the door and escorted me to the bandstand and waiting microphone. For the better part of an hour, I told an audience of several hundred, including many wives, of the investigation. Afterward, the applause was warm and prolonged, and many came forward to ask questions or contribute bits of information that had been heard from the natives. Mr. Schmitz and I had a drink at the bar and chatted for a while and then I was driven by the same circuitous route back to my “Presidential Suite.”

Just before I left the island, Bridwell began to cooperate. The invitation to NTTU had worked wonders. He readily admitted, “An ONI [Office of Naval Intelligence] man [Special Agent Joseph M. Patton] has been here checking on what you turned up last year. Most of the testimony couldn’t be shaken. A white man and woman were undoubtedly brought to Saipan before the war.”

The commander went on to expound his own theory: “I don’t believe Earhart and Noonan flew their plane in here. I think you’ll find that they went down near Ailinglapalap, Majuro and Jaluit Atolls in the Marshalls. The Japanese brought them to Saipan. A supply ship was used to take them to Yap in the western Carolines, and a Japanese naval seaplane flew them to Saipan. That’s why some of your witnesses said they came from the sky.”

“What have you got that’s tangible to prove that?” I naturally wanted to know.

“I think you’ll find all the proof you need,” replied Bridwell, “contained in the radio logs of four U.S. logistic vessels which were supplying the Far East Fleet in 1937. Remember these names: The [USS] Gold Star, [USS] Blackhawk, [USS] Chaumont and [USS] Henderson. I believe they intercepted certain coded Japanese messages that you’ll find fascinating reading.” (Editor’s note: Goerner reported nothing more about these four U.S. Navy ships in Search, or anywhere else, to my knowledge.)

Returning to San Francisco October 1, 1961, I was still without the last key to the Earhart puzzle, and without quite a few keys to NTTU. A few days later, a strange call came to me at KCBS from a Mr. Frederick Winter of the Central Intelligence Agency.

“I’d like to visit with you regarding a matter of national security,” he said.

“Of course,” I replied. “Come on up to our studios in the Sheraton-Palace.”

“Thanks, but I’d rather not,” rejoined Mr. Winter. “I’ll meet you in the lobby.”

From the back cover of The Search for Amelia Earhart: “Fred Goerner is a CBS radio broadcaster in San Francisco. A former college professor and World War II Navy Seabee veteran, he has been with station KCBS for seven years and has a popular afternoon program heard by tens of thousands of Californians. In 1962, he was honored with the Sigma Delta Chi National Journalistic Fraternity Distinguished Service Award for the best radio reporting in America. Born in Pittsburgh, Mr. Goerner now lives in San Francisco.” (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

“How will I know you?” I asked.

“Don’t worry about that,” assured Mr. Winter. “I’ll recognize you.”

Mr. Winter located me without any trouble, and suggested that we drop into the coffee shop for a bite of something. As long as I live, I’ll never forget that conversation. Mr. Winter had a dish of strawberry ice cream, and I had a cup of coffee. We talked, there in the coffee shop, about one of the best-kept, most important U.S. Intelligence secrets since the end of World War II.

“Mr. Schmitz has alerted us,” began Winter, “that you have turned up a good deal of information regarding NTTU and Saipan. Washington has asked me to talk to you about the matter and to ask you to withhold this information from publication or broadcast until you are given a release. We know you to be a good American, and we hope you will comply.”

I agreed. Mr. Winter didn’t know that I had already made that decision.

The conversation lasted a little more than a half-hour, and then, with a hearty handshake we parted. I have not seen Mr. Winter since, although we’ve had one brief telephone conversation.

Was Mr. Winter really from the CIA? I wondered for a while myself. I hadn’t asked for identification, but I wouldn’t have known the proper card anyway. For protection, I wrote a note to John McCone, head of the CIA in Washington.

“We’re happy to inform you that Mr. Frederick Winter is the man he represents himself to be,” was the answer.

Lengthy conversations began with the Navy Department about whether an expert was to study the remains. The Navy stipulated a number of things that must be done before the package could be released; among them was written permission from the next of kin. There was no definite indication the remains were those of Earhart and Noonan, but the Navy wanted as much time as possible and was taking no chances.

Dr. Frank Stanton of CBS flew out from New York, and the entire situation was discussed. We all strongly felt that nothing should be broadcast or printed before a positive identification of the remains could be made. If identification was not possible, the package could be returned to Saipan without publicity. The primary consideration should be for next of kin.

I visited Amelia Earhart’s sister, Mrs. Albert Morrissey, in West Medford, Massachusetts, and presented the facts of the total investigation.

She thanked me for my efforts and granted permission on behalf of Amelia’s mother, who has since passed away [Oct. 29, 1962] at ninety-five years of age.

A week later, I met Mrs. Bea Noonan Ireland, the remarried widow of Fred Noonan, now living in Santa Barbara, California. She also gave her consent to do whatever was necessary to write an end to the mystery.

Original caption from Search: “At nationally broadcast KCBS news conference in San Francisco, November 1961, the author (at table, right) is questioned by newsmen about package of remains being flown in from Saipan. Don Mozley, KCBS Director of News, sits at table with Goerner. Author’s Photo. (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

Dr. Theodore McCown, University of California anthropologist, was then asked to do the study should the Navy release the remains. He agreed.

It was another month before Navy permission was granted, and unfortunately, we had to learn of it from a wire service. A previous arrangement had been made for Father Sylvan to take the package from Saipan to Guam, address it to Dr. McCown, and ship it by commercial airliner to its destination.

Navy permission went direct to Saipan, and Father Sylvan carried through with his part. Someone on Guam, however, perhaps a customs official, leaked the story to a representative of Associated Press, and it was on every broadcast and every paper in the country before we could do anything to stop it.

There was nothing to do but admit we had been pursuing the investigation.

Dr. McCown’s study took a week, and his findings were disappointing in the extreme. Instead of two people, we had found three, perhaps four. At least one man and one woman were represented by the remains, but the strongest indications were that these people had been indigenous to the Saipan area. The “zinc-oxide” fillings that had excited the dentists on Saipan turned out to be calcified dentine. X-rays showed there were no metallic fillings present. “The hypothesis that the remains represented those of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan,” wrote Dr. McCown, “therefore is not supported.”

Privately, however, McCown told us, “Don’t be discouraged. You may have missed the actual grave site by six or sixty feet. That’s the way it is with archeology. In all my experience, I have never known a story with as much testimony supporting it as this one, not to have some basis in truth.”

Thomas Devine was also disappointed. His disappointment turned to frustration when he saw a complete set of photographs I had taken of our excavation and the surrounding area.

You were on the wrong end of the cemetery,” he wrote. “I’m sure now that the site was outside the northern perimeter, not the southern. There was a small dirt road that ran by the north side, too. Did you try to match that one photo against the mountain from the north side?”

From Search: “Dr. Theodore McCown, University of California (Berkeley) anthropologist, announces at December 1961 news conference his finding that the remains were not those of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan. Center background is Jules Dundes, CBS Vice-President and General Manager of KCBS Radio, San Francisco. Author’s Photo.” (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

I admitted I hadn’t because the jungle had grown too high in that area.

Nineteen sixty-one’s news reached the front page of nearly every newspaper in the nation, and a number of persons were motivated to come forward with bits of information. (Editor’s note: Here Goerner exaggerates the media coverage his investigation received, as I’ve found no evidence that any major newspapers published a single story about Goerner’s four Earhart investigations on Saipan in the early 1960s. Many smaller newspapers around the country did run stories produced by the San Mateo Times, Associated Press and United Press International, as shown in this clip from the Desert Sun, a local daily newspaper serving Palm Springs and the surrounding Coachella Valley in Southern California. But I’ve searched in vain for any traces of Goerner’s early 1960s Saipan investigations in papers such as the New York Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune or Los Angeles Times, to name just a few of the prominent newspapers that blacked out news of the search for Amelia Earhart on Saipan.)

Eugene Bogan, now a Washington, D.C. attorney, had been the senior Navy military government officer at Majuro Atoll in the Marshalls after the January 1944 invasion. Bogan claimed that several natives told him that two white flyers, one of them a woman, had landed their airplane near Ailinglapalap, close to Majuro, in 1937, and were taken away on a Japanese ship bound for Saipan. “The name of one of the natives is Elieu [Jibambam],” Bogan said. “Elieu was my most trusted native assistant.”

Charles Toole, of Bethesda, Maryland, now an expert in the Manpower Division of the Under Secretary of the Navy, had been an LCT (landing craft tank) Commander, plying between the same islands in 1944. “Bogan is absolutely right,” said Toole. “I came across the same information myself.”

Why didn’t Bogan and Toole file an official report on their findings?

“We were discouraged by the senior officer responsible for that over-all area in the Marshalls,” they replied. “The reason he gave was that there wasn’t any sense in raising false hopes at home that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan might still be alive.” (End of Part III.)

![Fishing boat story 5 This story appeared at the top of page 1 in the July 13, 1937 edition of the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania)-Globe Times. “Vague and unconfirmed rumors that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan have been rescued by a Japanese fishing boat without a radio,” the report began, “and therefore unable to make any report, found no verification here today, but plunged Tokio [sic] into a fever of excitement.” The story was quickly squelched in Japan, and no follow-up was done. (Courtesy Woody Peard.)](https://earharttruth.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/fishing-boat-story-5.png?w=616&resize=616%2C352#038;h=352)

Recent Comments