I received an email from Guam researcher Tony Gochar (see p. 263-264 Truth at Last) recently that I wasn’t expecting, about something that’s been sitting in plain sight for so long without being addressed that I had taken it for granted. (Boldface emphasis mine throughout.)

Most readers of this blog are familiar with the so-called “Truk overflight” theory, by which Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan, instead of flying east toward Howland Island, first headed north to Truk Lagoon, now part of Chuuk State within the Federated States of Micronesia. During World War II, Truk was Japan’s main base in the South Pacific theater, a heavily fortified base for Japanese operations against Allied forces in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, serving as the forward anchorage for the Japanese Imperial Fleet.

The long-theorized “Truk overflight” was initially described by Fred Goerner in the final chapter of The Search for Amelia Earhart:

When Amelia and Fred took off from Lae, New Guinea, they did not fly directly toward Howland Island. They headed north to Truk in the Central Carolines. Their mission was unofficial but vital to the U.S. military: observe the number of airfields and extent of Japan’s fleet servicing facilities in the Truk complex, and prove the advantages of fields for land planes on U.S. held islands on the equator.

Flight strategy had been carefully developed during the around-the-world trip. A point-to-point speed of not more than 150 miles per hour had been maintained throughout.

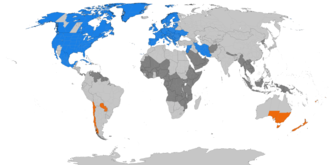

This graphic appeared in the September 1966 issue of True magazine’s condensation of Fred Goerner’s recently published The Search for Amelia Earhart, with this cutline: “Double line shows Earhart’s announced course to Howland Island. Author believes she flew first to Truk instead to study secret Japanese base, then got lost and landed in Mili Atoll. Captured by the Japanese, she was taken along dotted line to other bases. Ship below Howland is U.S. Coast Guard’s Itasca, Earhart’s assigned contact.”

In 1937, U.S. intelligence would have been extremely interested in the status of this naval base, once known to Allied forces as Japan’s “Gibraltar of the Pacific,” and Amelia might have been asked to observe and possibly even take some photos with her small, hand-held Kodak camera. The Electra would have arrived over Truk at about 7 p.m. local time, with plenty of daylight left, or so I believed the basic theory held. Of course, we have no proof that Amelia attempted to perform such a mission, but her actions during the final flight suggest something very strange was afoot, and she had two meetings with top U.S. officials during April 1937, according to Margot DeCarie, her personal secretary. (See Truth at Last for more.)

For more background on the Truk overfly theory, please see my post from Dec. 14, 2015, “Bill Prymak analyzes Earhart-as-spy theories” and Jan. 2, 2019, “Art Kennedy’s sensational Earhart claims persist: Was Amelia on mission to overfly Truk?”

Tony Gochar’s recent message, which he began with, “Just a few thoughts about the Richards Memo,” went immediately to an entirely different subject:

One of the basic thoughts I had about Earhart going to Truk to take pictures was daylight. Google Earth Pro has a feature called sunlight slider. You can locate where you are interested in daylight –Truk, pick a date (the year should not make a difference), and slide a scale which will give a time of day and the amount of sunlight at the location.

This part of the world does not have those long summer days. At 7:00 p.m. you can see almost total darkness at Truk on July 2. The other concern I had was weather. The best I could come up with is the attached Monthly Weather Review. It doesn’t cover the area of Truk, but it would if a big storm was heading across the Western Pacific. For Earhart to go to Truk is not something I take seriously.

For the other comments about Japanese radio intelligence I have a few sources. They had the capability to RDF (radio direction finding) her flight. They had the capability to listen to her broadcasts. Since I did that very kind of work in the USAF I am very certain they followed her track. I can’t describe the details of what I did, but I would have certainly listened for her. The U.S. radio direction finding stations in the Pacific followed her. I will provide details in a later email.

As we have discussed many times some of these documents are still classified and who knows when they will be declassified.

I’ve doubted little, if anything, that the experienced, detail-oriented Gochar has told me, but as a non-tech type, I found the Google Earth Pro “Sunlight Slider” a bit user-unfriendly. But William Trail, a retired Army officer, aviator and longtime contributor to this blog, soon found and sent the Sunrise and sunset times in Puluwat Atoll, Chuuk, Micronesia, which confirmed Gochar’s claim that the Sunset Slider revealed darkness at Truk on July 2 at 7 p.m.

Sunrise, sunset and twilight end, on July 2 at Puluwat Atoll, Chuuk, among other readings on the Sunrise-sunset.org site, are 5:50:52 a.m., 6:23:31 p.m., and 6:46:14 p.m. respectively, which makes it dark indeed at 7 p.m. on July 2 of any year. Further, the World Time Zone Map shows that Lae, New Guinea and Chuuk Lagoon, formerly Truk Atoll and now part of Chuuk State within the Federated States of Micronesia, are in the same time zone.

As seen in the map above, found on the now-defunct Mystery of Amelia Earhart website, created by William H. Stewart, a career military-historical cartographer and foreign-service officer in the U.S. State Department and former senior economist for the Northern Marianas, the distance from Lae to Truk is 888 nautical miles, or 1,022 statute miles, (another source says it’s 1,620 kilometers, 1,006 miles per a-kilometers-to-miles converter), but who’s quibbling? The total distance from Lae to Truck to Howland Island is 3,250 statute miles, compared with 2,556 miles when flying direct from Lae, and indeed pushes the range limits of the Electra, said to be 4,000 miles in the absence of headwinds, though that was certainly possible.

After receiving Gochar’s message, the Truk overfly theory, as I had conceived it, was suddenly on its deathbed, at least in my own mind. But before administering Last Rites, I decided to check a few more numbers, just to be sure. I was surprised to see that for a flight leaving Lae at 10 am, it would have to average 114 mph for a nine-hour trip that arrives at 7 p.m. Why had this 7 p.m. arrival time been stuck in my mind in such a sacrosanct way? I don’t know, perhaps many online conversations on the Amelia Earhart Society forum had implanted it, but I can’t find a solid reference for it, and I no longer have access to the AES website, which has been all but defunct for years.

Far more likely, the Earhart Electra would have been maintained at an average speed of 135 mph, or even 150 mph, over the trip to Truk, a speed that had been common throughout its world flight. An average of 135 mph would have covered the 1,022 miles in 7.57 hours, and put the plane over the Japanese-held atoll about 5:30 p.m., with enough light to do whatever she might have been “asked” to do. A higher average speed, of course, would have brought Earhart and Fred Noonan over Truk even earlier in the day.

Daylight saving time regions: Northern hemisphere summer (blue); Southern hemisphere summer (orange); Formerly used daylight saving (light grey); Never used daylight saving (dark grey). As the map indicates, daylight saving time has never been used in Papua New Guinea (dark grey area just above eastern tip of Australia.

Like Gochar, William Trail doesn’t put much stock in Fred Goerner’s 1966 theory. “I understand that it must remain a possibility until it can absolutely, positively be ruled out, but no, I’m not an advocate of the Truk overflight theory,” Trail wrote in an Oct. 1 email. “Flying from Lae, New Guinea to Howland Island by way of Truk for the purpose of taking aerial photos would have been a very long flight that would have taxed the capabilities of crew and aircraft to the max. The potential for failure, and disaster, was great. The odds for pulling it off and getting away with it were short. There was very little room for any error, or anything to go wrong, and we know that “Murphy” always tags along on the manifest. In my opinion, there was too just much risk for too little potential reward.”

![Fishing boat story 5 This story appeared at the top of page 1 in the July 13, 1937 edition of the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania)-Globe Times. “Vague and unconfirmed rumors that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan have been rescued by a Japanese fishing boat without a radio,” the report began, “and therefore unable to make any report, found no verification here today, but plunged Tokio [sic] into a fever of excitement.” The story was quickly squelched in Japan, and no follow-up was done. (Courtesy Woody Peard.)](https://earharttruth.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/fishing-boat-story-5.png?w=616&resize=616%2C352#038;h=352)

Flight planning aspects relating to a possible Earhart spy flight

Now that we are talking about Earhart’s role in gathering intelligence about Japan’s actions in the Mandated Islands, I decided to look at this from a piloting and aircraft performance point of view. It turns out that there are actually two different theories. One, that she was a spy herself, flying over the Japanese held Islands and taking pictures of their installations with cameras hidden in her airplane. A second theory is that she was not taking pictures herself but that she would stage a disappearance to give the U.S. Navy the excuse to search the Mandated Islands so that the Navy could take pictures of Japanese installations. We need to look at these two different theories separately.

The islands we are interested in were claimed by Spain based on discovery. These islands were sold to Germany in 1899. They were occupied by Japan in October 1914, shortly after the start of WW 1. After the war the League Of Nations recognized Japan’s fait accompli and granted Japan a mandate to administer the islands, thus the name the “Japanese Mandated Islands.” In spite of the maps that you may have seen with lines outlining the area covered by the Mandate, which include vast areas of open sea, it is important to keep in mind that these lines were drawn for the convenience of the map maker and do not mean that Japan had any claim to these ocean areas. What the lines actually denote is that any island found within the lines (except Guam and Wake) are subject to the mandate given to Japan. All that was transferred to Japan by the League of Nations Mandate were the original rights that had belonged to Germany to control the islands and the territorial seas surrounding the islands. Japan could not be given any more rights than Germany had held. By international law, the territorial seas extended only three nautical miles from the nearest shoreline,(this was changed to twelve nautical miles by international agreement in 1982.) Beyond the territorial seas (three nautical miles then, twelve nautical miles now) are International Waters where ships of any nation can sail. This includes naval vessels of every country which are also free to conduct flight operations over International Waters. The U.S. Navy had the right to operate its aircraft as close as three nautical miles from each of the Mandated Islands and could have obtained much information by taking photos from these locations. The U.S. Navy routinely conducts “Freedom Of Navigation” operations to assert these rights, an example of which resulted in the Gulf of Sidra Incident in 1981. Some believe, that in spite of international law, that Japan might have attacked or protested if the U.S. Navy had conducted operations in International Waters near the Mandated Islands but it is obvious that Japan was not ready to pick a fight with the U.S. in 1937. This is clear from the USS_Panay_incident. On December 12, 1937 Japanese planes sank the U.S. Navy gunboat Panay in the Yangtze river, killing 3 and wounding 42. Japan promptly apologized and “paid an indemnity of $2,214,007.36 to the United States on April 22, 1938.” For more information about these islands see:

World War 2 Pacific Island Guide

The island groups are the Carolines, the Marshalls and the Marianas. The islands of most interest were Palau, Saipan, Truk, Ponape and Jaluit. They are north of the line that stretches from Palau in the west to Mili in the east. However Guam remained an American possession and it is at the southern end of the Marianas chain, 130 SM south of Saipan. ( I will use statute miles in this discussion since our prior discussions about airplane performance also used statue miles and statute miles per hour instead of nautical miles and knots.) Wake Island, to the northeast, was also in American hands. See map 1 and map 2 and Google Earth image 3 and image 4. Image 5 shows the relationship of the Mandated Islands to Lae and Howland. Image 6 shows the route from Lae to Howland which is 2560 SM long. ( I have rounded the mileages off to 10 SM which are sufficiently precise enough for this discussion.)

The distance from Lae to Palau is 1300 SM; Lae to Truk, 1030 SM; Lae to Ponape, 1220 SM; and Lae to Jaluit, 1790 SM. From Palau to Truk is 1180 SM, Truk to Ponape is 440 SM, Ponape to Jaluit 780 SM and from Jaluit to Howland is 1020 SM. If Earhart flew to Palau first she could have overflown the other islands on the way to Howland and this route would be only 130 SM longer than flying directly from Palau to Howland. If, instead of going to Palau, her first destination was Truk, then overflying the other islands on the way to Howland would add only 20 SM so there would be no reason to not take advantage of the orientation of the islands by flying directly to Howland. See image 7.

Let’s look at the possibilities, first the route to Palau and then overflying the other islands. They took off from Lae at ten a.m. which was 0000 Z July 2, 1937. (We will use GMT for all the times, Zulu time.) Flying at 150 mph it would take 8 hours and 40 minutes to fly the 1300 SM to Palau so they would arrive at 0840 Z. Then 7 hours and 52 minutes to Truk, arriving at 1632 Z. Then 2 hours and 56 minutes to Ponape, arriving at 1928 Z. Then 5 hours and 12 minutes to Jaluit, arriving at 0040 Z, July 3, 1937. Then the final leg to Howland would take 6 hours and 48 minutes finally arriving at Howland at 0728 Z July 3, 1937. The total distance for this route would have been 4,720 SM and the total time en route 31 hours and 28 minutes. If she just went to Palau and then directly to Howland the distance would have been 4,590 SM taking 30 hours and 36 minutes and arriving at Howland at 0636 Z July 3rd. This is for a no wind condition. If we assume a 25 mph wind out of the east then the times become 0725 Z at Palau; 1652 Z at Truk; 2023 Z at Ponape; 0138 Z July 3rd at Jaluit and 1047 Z July 3rd at Howland for a total time 34 hours and 47 minutes.

There are a number of problems with this proposed route. First, she didn’t have enough gas to fly for 34 hours and 47 minutes. Second, the 25 mph east wind added 498 statute air miles to the route making the route cover 5,218 statute air miles which is much greater than any range claimed by Lockheed and also much greater than the range calculated in our prior discussions. Third, Earhart reported at 1912 Z July 2nd that she thought she was at Howland which was fully 15 hours and 35 minutes earlier than she would have arrived if she had overflown Palau. If she had flown this route then she would have been about 2100 SM away from Howland at the time of this radio report. Everybody in the radio room on Itasca at 1912 Z agreed that they believed Earhart was very close at that time, including the two independent wire service reporters. I have shown previously that she couldn’t fly faster without burning fuel at a much higher rate which would have reduced the range still further. If she had flown at full continuous power of 1100 hp she would have run out of gas at 0913 Z while still on the leg between Palau and Truk. Fifth, sunset at Truk on July 2nd was 0805 Z meaning that she would be over Truk in the middle of the night when it would have been impossible to take any photographs. (Sunset at Palau was 0920 Z so she would have been able to take pictures there.) For all of these reasons we can dismiss Palau from Earhart’s plans.

Next let’s consider a route directly to Truk and then overflying Ponape and Jaluit on the way to Howland. See image 8 and image 9. (We will assume the same 25 mph east wind.) She would have arrived over Truk at 0719 Z which is 46 minutes prior to sunset. She would then overfly Ponape at 1050 Z which is 2 hours and 50 minutes after the sun went down at Ponape. She would arrive over Jaluit at 1704 Z 1 hour and 31 minutes prior to sunrise at Jaluit. She would get to Howland at 0109 Z July 3rd.

There are also problems with this route. First, she would arrive 5 hours and 57 minutes after the time she reported being near Howland and the plane would still have been about 750 SM away from Howland. Second, this route would cover 3,772 statute air miles and take a total of 25 hours and 9 minutes. Although various calculations show that she might have been able to fly this far and stay aloft for this period of time, a route this long would have left little or no reserve and it is unlikely that she would have embarked on such a risky route. Third, if she were willing to fly with no reserve it would have made much more sense for her to take off two and a half hours earlier so that she could have photographed both Truk and Ponape during daylight hours. She did not seem to be in a hurry to depart Lae and she had planned to leave even later in the day according to her earlier radiograms. Why would she miss the opportunity to photograph two Japanese bases when all she had to do was get out of bed just a few hours earlier?

Next we look at a flight directly to Ponape then on to Jaluit and Howland. Since it is 1220 SM from Lae, Earhart would have arrived over Ponape at 0923 Z, 1 hour and 38 minutes after sunset. Then over Jaluit at 1537 Z, which was the middle of the night. Then to Howland at 2342 Z. The total time would be 23 hours and 42 minutes and the distance covered 3,555 statute air miles. Since this route saves 217 statute air miles and 1 hour and 27 minutes off the previous route it is more doable but there are still problems. First, nothing would have been accomplished since she would not be able to get any pictures from any of the islands. If she was planning this route she would have taken off earlier so as to arrive over Ponape during daylight. Second, the fuel reserve would still be minimal and not a comfortable level for the crew. Third, they would arrive 4 hours and 30 minutes after the time they reported being near Howland and this report would have been made when the plane was still about 570 SM away from Howland. See image 10.

The last route to consider is direct to Jaluit, then on to Howland. It is 1790 SM to Jaluit which would take 14 hours and 1 minutes so arriving in the middle of the night at 1401 Z which is 4 hours and 34 minutes prior to sunrise at Jaluit so nothing could have been accomplished by flying this route. Then on to Howland, arriving there at 2206 Z covering a total distance of 3315 statute air miles and arriving 2 hours and 54 minutes after she reported being at Howland and this report would have been made when the plane was still 370 SM away from Howland. Even though this is the shortest route, since no photos could be taken, it wouldn’t have made any sense to make this flight. See image 11.

So my conclusion is, that from the flight planning aspects, is doesn’t appear to me that she was attempting to fly over Japanese held islands in order to take photos and to gather intelligence for the U.S. Government.

https://sites.google.com/site/fredienoonan/discussions/flight-planning-aspects-relating-to-a-possible-earhart-s-spy-flight

LikeLike

Gary,

You are re-posting your thesis of several years that those of us who are really interested have seen on your site. And with all the possible scenarios you cover, you don’t address the route we’re considering in my post — from Lae to Truk to Howland. The total distance from Lae to Truck to Howland Island is 3,250 statute miles, compared with 2,556 miles when flying direct from Lae, and indeed pushes the range limits of the Electra, said to be 4,000 miles in the absence of headwinds, though that was certainly possible. That’s all that’s necessary here for that aspect of the discussion, but thanks anyway.

Mike

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gary,

You have done some impressive math in your evaluation of various theoretical flight routes. I would offer a correction to one part of your post. You stated:

“There are a number of problems with this proposed route. First, she didn’t have enough gas to fly for 34 hours and 47 minutes. Second, the 25 mph east wind added 498 statute air miles to the route making the route cover 5,218 statute air miles which is much greater than any range claimed by Lockheed and also much greater than the range calculated in our prior discussions.”

Wind does play a part in Navigation and Flight Planning, but it does not “add mileage”. The mileage of any given route remains constant. Wind affects ground speed and causes left or right drift which needs to be taken into account in choosing a heading for the aircraft to stay on course.

As you correctly point out, a headwind will cause the aircraft to cover the route more slowly (given a set cruise airspeed) and this will prolong the time of flight.

The total time that an aircraft can stay airborne is known as maximum endurance (Max Endurance), and it is based on how much fuel can be placed in the aircraft and on flying at the most efficient airspeed.

A flight plan will also include a minimum amount of reserve fuel to have on board when arriving at the destination. This is so that the pilot can fly to a secondary field if landing is not possible at the primary destination. So this required reserve fuel cannot be counted in determining Max Endurance time for a mission.

Besides the amount of fuel on board and the chosen airspeed, another factor which enters into determining endurance time is crew fatigue. The US Navy determined that although their PBY Catalina could remain airborne for 24 hours, crew fatigue played a major part in planning flight operations.

LikeLike

One factor often mentioned is the maximum range of the Electra with a full load of fuel, i.e. 1,150 gallons. However, at no point during any stages of the World Flight did the Electra fly with a full load of fuel.

How much was on board for the flight to Howland is the subject of debate. Eric Chater, General Manager of Guinea Airways indicates that she took off with 1,100 gallons whereas a report in the Sydney Daily Telegraph states that only 950 gallons was loaded aboard at Lae. The source for the latter figure implies it may have been Fred Noonan himself, but this is unconfirmed. Kelly Johnson’s fuel calculations also suggested that the amount of fuel was unlikely to have been 1,100 gallons for this leg of the flight.

There are several factors that suggest the figure of 1,100 gallons might not be accurate:

1) Amelia wrote a letter to the Director of Civil Aviation in the U.K. (she would be flying over British overseas territory and so would require permission) in which she states that for the longest legs of her flights over the Pacific she would probably use about 1000 gallons.

2) It has been suggested that the runway at Lae was not long enough for them to take off with this much fuel.

I’ve read Chater’s report many times and I can’t decide if his reference to 1,100 gallons is an estimate, or a stated fact although I tend to lean more to the former.

LikeLike

The “950” number was in an Australian newspaper, Australia uses Imperial gallons. 1.100 U.S. gallons equals 915 Imperial Gallons. So either Noonan did the conversion before he told the reporter or, much more likely, the reporter did the conversion when writing his story for the Australian audience.

Certainly Chatter did not measure the amount of fuel in the plane but got that information from Noonan or Earhart. The 1100 number is made more reliable with the extra information about preserving her 100 octane for takeoff leading to the reluctance to fill up the tank that still contained 100. Obviously, Chatter did not just make up this detail but must have been told that detail by Noonan or Earhart.

LikeLike

What interest me is that a straight conversion between imperial and US gallons would have been a straightforward calculation, so my question is why the difference? A simple conversion error does not appear to account for this because 1,100 US does not equal 950 Imperial. The devil, as always, is in the detail.

1,100 gallons is very close to the maximum fuel capacity and would allow a maximum endurance close to the Electra’s maximum. What puzzles me is why such an excess of fuel for a 2,556 miles flight? There was similar excess on any other leg and although Lae to Howland was arguably the most difficult it does run counter to the fuel amounts for the other legs.

I would argue that there exists sufficient doubt over the fuel load to argue against 1,100 gallons. Earhart, incidentally did not specify to the British Director of Civil Aviation whether this was Imperial or US ( I have a copy of the original).

If the true amount was 950, then this would change things considerably.

LikeLike

“Nine fifteen” sound a lot like “nine fifty,” and an easy mistake to make if being dictated over a phone line or anywhere else along the publication chain.

LikeLike

Replying to your earlier question:

Next let’s consider a route directly to Truk and then overflying Ponape and Jaluit on the way to Howland. See image 8 and image 9. (We will assume the same 25 mph east wind.) She would have arrived over Truk at 0719 Z which is 46 minutes prior to sunset. She would then overfly Ponape at 1050 Z which is 2 hours and 50 minutes after the sun went down at Ponape. She would arrive over Jaluit at 1704 Z 1 hour and 31 minutes prior to sunrise at Jaluit. She would get to Howland at 0109 Z July 3rd.

There are also problems with this route. First, she would arrive 5 hours and 57 minutes after the time she reported being near Howland and the plane would still have been about 750 SM away from Howland. Second, this route would cover 3,772 statute air miles and take a total of 25 hours and 9 minutes. Although various calculations show that she might have been able to fly this far and stay aloft for this period of time, a route this long would have left little or no reserve and it is unlikely that she would have embarked on such a risky route. Third, if she were willing to fly with no reserve it would have made much more sense for her to take off two and a half hours earlier so that she could have photographed both Truk and Ponape during daylight hours. She did not seem to be in a hurry to depart Lae and she had planned to leave even later in the day according to her earlier radiograms. Why would she miss the opportunity to photograph two Japanese bases when all she had to do was get out of bed just a few hours earlier?

LikeLike

I don’t remember if Earhart specified U.S. or Imperial gallons in her letter to the U.K.

LikeLike

1,100 gallons sounds right as the right main wing tank was approximately 1/2 full with 100 octane fuel (97 gallon tank?) and it was not topped off as AE wanted that available for full power on takeoff and didn’t want it diluted with 87 octane.

LikeLike

kcb,

I suppose we could play with our calculators and whiz-wheels and run the numbers from now till Judgement, as well as argue the issue of U.S. gallons vs Imperial gallons. We can also debate the question of the partially filled tank containing pure, undiluted 100 octane AvGas to be used for takeoff. For me, the answer to the fuel-on-board-at-takeoff-from-Lae question is answered by the actual takeoff itself. We’ve read all the eyewitness accounts, and we have seen the film.

From TTAL, 2nd Ed., page 28: “Iredale [Vacuum Oil representative Bob Iredale at Lae] filled and topped off the Electra’s tanks before it’s Lae departure and described the take-off in a letter to Fred Goerner:

We had a grass strip some 900/1000 yards long, one end the jungle the other the sea. Earhart tucked the tail of the plane almost into the jungle, brakes on, engines full bore and let go. They were still on the ground at the end of the strip, it took off lowered toward the water some 30 feet below and the props made ripples on the water. Gradually they gained height and… some 17 miles out I guess they may have been at 200 feet.”

That takeoff was real sporty and just a cat’s whisker from disaster” It’s clear to me that NR16020 was loaded to it’s maximum limit when it took off from Lae, and it couldn’t have been loaded with anything other than fuel.

All best,

William

LikeLiked by 1 person

Look at the video of the takeoff and you will see that Earhart failed to use the procedure required by Lockheed Report 487 pages 2, 15, and 21-23 for takeoff. She was required to place the flaps in the 30 degree position. Since she didn’t do that it caused to ground run to be much longer than the Lockheed testing and report showed she should have required. “SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS.

*****************************************

The important results from the report may be summarized as

follows:

(1). Best take–off distance is obtained using a 30° wing flap

setting. The tail of the airplane should be lifted off

the ground as soon as possible and held up through the

take–off run.

(2). On a hard run–way, using 600 BHP per engine, the take-off

distance is 2100 feet at sea level.”

So, no, she was not overloaded with fuel since the plane should have taken off in only 2100 feet if she was at the full gross weight of 16,500 pounds and she wouldn’t have been that heavy even if she had every tank full plus a couple of jerry cans and all that gold supposedly found in the airplane near Buka. Her forgetting to put the flaps in the takeoff position added 500 feet to the takeoff run.

LikeLike

With all these calculationst your fingertips (they’re not at my fingertips, I just looked) you ought to be able to calculate if her runway at Howland was sufficient for her takeoff with a full load of fuel. I remember someone claimed, maybe Calvin, that the runway was not long enough, therefore she never intended to land at Howland, etc. I thought the runway was long enough but I’m no expert. Just a very minor point, well, not minor to her if she couldn’t take off from there.

David

LikeLike

I’m not going to go through the whole calculation again (see my other post of today) but the runways were plenty long enough for her to takeoff at Howland. This is especially obviously since it was a thousand mile shorter from Howland to Hawaii so she could depart with a much reduced fuel load. If you look at any textbook on airplane performance you will see that the approximation of takeoff distance varies with the square of the weight, double the weight and the distance increases four times. But you can do the actual calculation for Earhart’s plane by using the information in Lockheed Report 487.

LikeLike

Gary,

I don’t want to put you into doing a lot of work for a hypothetical question. Months ago Calvin postulated that the runway at Howland was too short for her takeoff and no one disputed that except me. All I had to do was look up her takeoff distance but of course the specs don’t say with all that extra fuel which would lengthen the distance or maybe she didn’t need all the extra fuel because the flight was shorter. My take was that the runways were as long as Lae or almost as long so she could have taken off OK. But I am an amateur so I was asking you, the expert. I don’t understand why Calvin said she could not take off from Howland. It doesn’t matter much now, I guess.

David

LikeLike

We don’t actually need to do any calculations because the runways at Howland were longer than the runway at Lae! There were three runways there, 2250, 2600 and 4100 feet long. We have the test data from the Lae takeoff that she used between 2550 and 3000 feet according to two witnesses. And that was after she screwed up and didn’t lower the flaps to the takeoff position which would have shortened the takeoff by 500 feet. The plane weighed about 15,000 pounds when it took off at Lae and that was with 6,600 pounds of fuel onboard for the 2552 mile flight to Howland.

Since in is only 1900 miles from Howland to Hawaii she would have a lower fuel load of about 818 gallons, only 4,900 pounds of fuel. That is a good approximation because we know that they had 850 gallons on board for the flight in the other direction from Hawaii to Howland. So the plane would weigh about 1700 pounds less at 13,300. Takeoff distance varies with the square of the weight. 13,300 / 15,000 = 0.866 which squared =0.786. So the takeoff distance at Howland would be (at most) 3,000 feet (Lae largest estimate of takeoff distance) x 0,786 = 2,358 feet. Had she used the flaps at Lae she would have taken off in 2,500 feet times = 1,965 feet. Using the computations in Lockheed Report 487, 13,300 / 16,500 = 0.81, squared = 0.65 x 2,500 (no flaps) = 1,624. With flaps, 2,100 x 0.65 = 1,365 feet.

So even using the data based on terrible performance the plane would take off, in the worst case, in only 2,358 feet so she could have easily taken off on either the 2600 foot or the 4200 foot runway.

Based on using the proper procedure from Lockheed the plane would only need 1,365 feet and could also use even the shortest runway at Howland. And this doesn’t allow for the helpful effect of wind. With no wind the 4200 foot runway is the one to use. If there was a strong wind from the east making it difficult to control the plane on the long runway due to the cross-wind then the plane can take off on either the shorter runways in a shorter distance than with no wind.

See the Cooper Report: https://tighar.org/Projects/Earhart/Archives/Documents/Cooper_Report/Cooper.html

and https://tighar.org/Projects/Earhart/Archives/Documents/Report_487/Report487.html

LikeLike

The length of the runway at Lae, which was unpaved, is very important in any discussion regarding the amount of fuel onboard, since these factors would dictate the maximum take-off weight. And at Lae the maximum take-off weight would be nowhere near the Electra’s published weight or fuel capacity.

The video of their take-off from Lae and the eye witness accounts describing the difficulty the Electra had getting airborne all point to the fact that the aircraft was loaded to the maximum weight permitted by the runway, rather than the aircraft’s published maximum weight – two very different things. Kelly Johnson’s very detailed calculations were based on paved runways and not grass strips like that at Lae.

When taking these factors into account I don’t believe that Lae would have permitted a take-off with 1,100 gallons of fuel on board.

LikeLike

Well, you are wrong because you have a basic misunderstanding of the takeoff distance published in Lockheed report 487.

The runway was turf at Lae and not paved. Modern takeoff performance data is calculated for paved runways but Lockheed did the calculation for a turf runway since paved runways were a rarity in 1937. Page 2 of report 487 states that it takes 2,100 feet to take off “on a hard run-way” so I can see why you would think the calculation was for a paved runway. But look at page 21, where they go through the actual calculation, where is shows that the calculation was for “a good field with hard turf.” The calculation uses a coefficient of friction ( μ, mu) of .04 for the calculation which is the μ for turf. The μ for pavement is .02, for short grass μ is .05 and it is .10 for tall grass. The coefficient of friction affects the takeoff roll because it retards the acceleration, the greater the μ the slower the acceleration. This retarding force gradually drops to zero as more and more of the weight of the plane is carried by the wings as speed increases. At the same time the drag due to increasing air resistance increases which slows down the acceleration as the plane approaches takeoff speed. All of these factors are accounted for on pages 21-23 which steps you through the calculation and you can redo the calculations yourself by substituting your chosen value for μ. If you don’t want to go through the entire calculation you can use a rule of thumb to come up with a reasonable adjustment for longer grass at Lae. The rule of thumb is to increase the distance for takeoff from a paved runway ( μ = .02) by 7% for turf, 10% for short grass and 25% for tall grass. First back out the 7% for the turf runway that the calculation assumed and then apply the percent increase for different runway surfaces. But the runway at Lae was also described as “turf” and it looks like “turf” on the video, so the value calculated in report 487 should be applicable. At the worst, the runway is “short grass” and not “tall grass.” Using the rule of thumb would increase the takeoff distance only 50 feet more for “short grass” rather than “turf.”

If you want, you can also use the formulas on page 21 trough 23 of Report 487 for calculating the takeoff distance for different gross weights, flap position and for density altitude. If adjusting for gross weight you must first calculate te takeoff speed using the normal formula for lift. The takeoff speed also determines the dynamic pressure, “q”, which you need for the takeoff formula and also is needed for determining the final thrust from the table on page 21.

Page 21 of Lockheed report 487

“Mu The coefficient of friction of .04 corresponds to a good

field with hard turf.”

P1=D1-T1= 3180 – .148 x 458 x 27.5 = 1317#

S1= (16,500 / .0765) x [ 27.5 / ( 3660- 1317)] log e(3660/1317) =2590 feet

So the takeoff roll for the plane at full gross weight of 16,500 pounds is 2590 feet on a TURF runway like the runway at Lae.

IF she had followed the proper procedure laid out in Report 487 by placing the flaps in the takeoff position of 30 degrees it would have taken only 2,080 feet as shown on page 15 of the report.

Since there is no way the airplane could have been loaded all the way up to the maximum gross weight of 16,500 pounds or higher (even with the gold bars found in the plane in Buka) that if she took more than 2590 feet (and that is in dispute, compare Chater with Collopy) then it just shows that Earhart used poor pilot technique in addition to her failure to extend the flaps.

(I also studied Aeronautical Engineering at the University of Illinois)

LikeLike

Thanks Gary, I’m always prepared to learn something new!

LikeLike

Page 2, Lockheed report 487

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS.

*****************************************

The important results from the report may be summarized as

follows:

(1). Best take–off distance is obtained using a 30° wing flap

setting. The tail of the airplane should be lifted off

the ground as soon as possible and held up through the

take–off run.

(2). On a hard run–way, using 600 BHP p

LikeLike

You can download for free the current FAA flight navigator manual yourself at: https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/media/FAA-H-8083-18.pdf

LikeLike

Regarding takeoff distance the wild card is the actual condition of the runway, which can alter published data drastically. Flaps on takeoff? When I was a CFI the only time we taught students to use flaps on takeoff was during a “soft field” takeoff; the use of flaps (we typically used a lower amount, say 15 degrees) takes some weight off the wheels which reduces the resistance/friction on the soft surface, which in turn allows for quicker acceleration. Whether or not flaps would have been beneficial in this situation is hard to say (with all of the variables), but it is possible.

LikeLike

The next time you fly on an airliner look out the window on takeoff any I doubt you will be surprised to see that the flaps are down for takeoff. In a light trainer aircraft we usually use flaps for takeoff for “soft field” takeoffs, that is a flight instruction “rule of thumb” and is common in manuals for a particular type of aircraft. Some light aircraft manuals also specify a flap setting for normal, hard surface takeoffs. Just grabbing two manuals at random, the Piper Arrow manual specifies 25 degrees of flaps for hard surface normal takeoffs and my Aerostar manual specifies 20 degrees. Lockheed Report 487 specified 30 degrees of flaps and Earhart failed to use the proper procedure.

LikeLike

Gary,

Yes, I was referring to light aircraft, not airliners. Regarding turf runways, the “wild card” I was referring to has to do with the actual condition based on how hard/soft it is (recent rain or bone dry?) and is it wet or dry (rain or morning dew)….those things make a difference. Another factor is how smooth the runway is; I have seen some pretty rough ones, and others as smooth as a fairway. Those things are not easy to address using a chart or formula.

LikeLike

You also have to take into account that Lae was the busiest airport in the world at that tie because everything had to be flown to the gold mines, there were (are?) no roads in those mountains. So the runway had to be well maintained and there was money there to do it.

LikeLike

The US Army Air was planning an “accidental” overflight a month before the war started, from Wake towards the SW Pacific over the mandates for a look see.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Matt,

That’s an interesting bit of history that I’d like to learn more about. Please cite your source(s). Thanks.

All best,

William

LikeLike

Crickets, anyone?

Seriously, this begs the question of when exactly airstrips were constructed on the U.S. island possessions such as Guam, Midway, Wake, etc. The respective Wikipedia pages generally state late 1938 or early 1939. It seems that Richard Black already knew what he was doing when they scraped the strip on Howland. It even looks like they were planning to extend the east-west runway later. Loomis stated there was a 3000 ft. strip on Kanton Island in July 1937. Officially, the strip was built after Richard Black & Co. invaded and took possession for the Dept. of Interior. Since Loomis must have stopped there during the war he could have learned otherwise from the locals.

LikeLike

Does this eliminate the theory that she may have been persuaded to look at the Marshalls?

LikeLike

In regard to this theory or any others concerning spy missions, would not the government have known that the Japanese would have had the capability to track Earhart & Noonan’s flight, and stop them when required? Also, did she not have a special spy camera installed at one point.. she wold not have needed her own personal camera. Obviously, something was up due to her hush hush meetings with government representatives prior to the flight-but what exactly? So frustrating not to know for sure and that the answers lie in some stashed government files somewhere. And finally (I think I posed this question before) was Fred Noonan in on all this? is it possible he could have been left in the dark concerning their alternative “real” mission, and notified during the flight?

LikeLike

Dave,

Bill Prymak was vehement, and had a Lockheed employee who was a sworn source, that there were no special cameras installed. “There are only six inches between the floorboards and the belly skin,” Prymak wrote in the AES Newsletter of February 2011. “No surveillance cameras circa 1937 existed to fit those dimensions. Besides, a camera-control panel would of necessity be in the cockpit or on Fred’s table — pretty obvious to customs or mechanics working the aircraft.”

Mike

LikeLike

In all these calculations, by me or others much more qualified, there just doesn’t seem to be a logical conclusion to be reached. Us conspiracy theorists are drawn to the spy flight option like moths to a flame, it does give us our conspiracy theory fix. But the fix is wearing off, it appears more like the spy flight idea was dangerous, not realistic, and probably pointless almost 5 years before the projected war started. Mike’s point that her late starting time at 1000 AM made the spy flight not even practical I had not thought of, maybe she forgot to wind up her alarm clock before retiring for the night.

It would be interesting to establish a definite time that she arrived at her Mili Atoll for her crash stipulating that this is an indisputable fact and work backwards from there. Did she have time to do Truk and then fly directly over the Marshalls (in the dark) and arrive at Mili when she did? Or was too much time? Or could she have been “on” Howland I. but could not see it at 0843 and then flown all the way to Mili in the allotted time? Or were her Howland vicinity messages just recordings? Could she have been at Howland at 0843 and then flown all the way to Mili to crash there by mid or even late morning ? I would say NO. It’s a 5.7 hour trip and even with the time difference I don’t think it could be done.

So what conclusion can we reach from these speculations above? As usual, no conclusion. It’s getting like the Oak Island treasure hunt. But something quite important must have been going on or why would 80 years later we still get inundated with monthly sometimes expensive disinformations about her?

Stay Tuned,

David

It would be

LikeLike

Dave,

You misunderstand my point about the 10 am start time. The whole point was to show that instead of arriving at 7 pm, when it was dark and as I had assumed was a basic part of the theory, that she would have arrived well before it was dark if she flew at average speeds. So the theory remains alive, if only on life support.

Mike

LikeLike

I’ve never put much stock in the idea that Amelia was sent to overfly Truk. Aside from the fact that they would have to push to get there in order to take any meaningful pictures, the fuel load was probably insufficient. We know that the fuel load carried during the world flight was never anywhere near capacity and there is good evidence that the flight from Lae was no exception (Australian press and U.K. records). Little by little we are obtaining a clearer picture of what happened: i.e. she wasn’t on a secret spy mission and she certainly didn’t end up on Nikumaroro.

The truth will out and I firmly believe that she ended up in Japanese hands.

LikeLike

Greetings to All:

Is it me, or does the Truk overflight flight route depicted in the graphic map from the September 1966 issue of True magazine seem illogical? The graphic depicts a no-wind, straight-line course of approximately 105 degrees direct from Truk to Howland Island which slices through the northern Gilbert Islands between Makin and Butaritari Islands to the north of the indicated flight path, and Marakei and Abaiang Islands to the south of it. That’s fine so far as it goes. However, after passing east of the northern Gilberts, the depicted flight path indicates a left turn through 225 degrees to a new course of approximately 330 degrees toward Mili Atoll.

Now, if AE rolled the Electra into a left bank for a 2 minute Standard Rate Turn (3 degrees per second) it would have taken 1 minute and 15 seconds to turn through 225 degrees to bring the Electra’s nose around and roll wings level on the new course of 330 degrees — northwest toward Mili. The angle of bank required to achieve standard rate changes with true airspeed (TAS). The higher the TAS, the greater the bank angle needed to achieve a standard rate turn. I mention all the technical stuff about the turn only to illustrate that such a significant course change could not have been an accident due to compass error, or because of winds. It also could not have been gradual, or gone unnoticed. If such a turn was made, it was pilot induced. And that brings us to why?

Why after passing through the northern Gilberts when at a point approximately 500 to 600 miles give or take from landing on Howland Island would AE and FN suddenly make a 225 degree turn away from Howland, or safe refuge in the British-controlled Gilberts just to their rear, to fly straight into the teeth of the tiger — the Japanese Mandates — a hostile, denied area to land on Mili Atoll? The answer is, there is no answer. There is no plausible, sensible reason for AE and FN to do such a thing, especially if they’d just overflown Truk and taken photos with a hand-held camera.

Bottom line: This never happened. AE and FN landed on Mili Atol for sure, but it wasn’t because they became lost flying from Truk to Howland.

All best,

William

LikeLike

William,

That turn you are describing to head back toward Mili was taken from True magazine? It is the same as the flight path given in “Lost Star” by Randall Brink. Is it possible the True magazine article was taken from his book or vice versa? In his book I don’t think he gives any particular reason for her U-turn near Howland. I don’t think her flight happened that way. He has many curious events in his book that others don’t. He also is especially fond of her being given a new, much more advanced plane by Lockheed and he demonstrates this noting the records of her earlier flights and the remarkably fast times she made them in, certainly far faster than her old L10 could do. I think he has a strong point there.

Here’s a possible scenario: As Mike was pointing out, I think, that 7:30 PM arrival at Truk comes out of nowhere. Yes, it’s dark by then, but with her souped up plane she is easily able to arrive far earlier, say at 6:00 PM plenty of daylight left for photos. So then she heads off through the Marshalls. What on earth could she be looking for in the dark across those islands? Was there nothing to see? Maybe not. What was going on at Maloelap? There is Taroa. The books say the airfield was not built until 1939. But there’s this article. https://www.nothingunknown.com/content/2016/10/7/taroa-island. Maybe as the article hints, there was activity even as early as when she flew over it. Maybe that’s what she was specifically looking for.

Maybe there were already fighter planes there and this is where they came from that “forced her down.” Possibly there were some planes from the Akagi already there at the time. After all, no one knew that the airfield was active in a rudimentary way until she spied on it. Perhaps the Navy did not realize the progress that had been made there because no American had ever actually seen it, but the Navy suspected activity there. So I say she could have seen Truk in the daylight, then slowed down until daybreak over Taroa.

She almost made her escape but unfortunately the Japs caught her over Mili. To me, this is plausible. Of course there was no reason for her to view Mili, nothing there. Also no reason for her to land there unless she were forced down. But not only had the Japs started construction of the airfield in July 1937, they aready had some planes there. She was caught red handed. The Americans couldn’t object to the Taroa construction because they learned about it through breaking the code. Maybe Amelia’s observation was going to provide the basis for an, but that’s far-fetched. American objection to the obvious military construction by the Japs. So the voice of Amelia right on top of the Itasca was a recording, meant to fool the Japs. They were able to get a fix on the recordings because they were so loud and strong. She was never anywhere near there. Yes, this was the predecessor to the U2 spy plane. That is all.

Over and out.

David

LikeLike

David,

Yes, the graphic appeared in True magazine’s September 1966 issue, which featured a condensation of Fred Goerner’s recently published book, “The Search for Amelia Earhart.” However, essentially the same graphic also appears Randall Brink’s book, “Lost Star” (1994) 1st Ed. up front between the Contents page and Acknowledgments.

To put it gently, I would not rely on Brink for facts. For example, on pages 148 and 149 of his book Brink writes, “It is no exaggeration to say that Amelia flew into the midst of a major Japanese naval exercise then underway in the southeastern Marshalls, made up of at least three destroyers, one battleship, one seaplane tender, and the super carrier Akagi.” Really? As we have discussed at length, and firmly established as fact, Akagi was at Sasebo Naval Arsenal undergoing a major refit at the time. Brink additionally fails to give a proper account of IJN vessels engaged in this alleged “naval exercise,” does not state exactly how many destroyers participated, and does not provide the name of the battleship, or even the seaplane tender (Kamoi?). At least he doesn’t name the seaplane tender on page 149. Why? These are important details. Brink’s vagueness, to say nothing of his egregious error about Akagi, does not inspire confidence in his research or scholarship.

On page 149, Brink attributes the turn to AE and FN “having flown within 200 miles of Howland” and, “when they did not immediately see the island,” following “logical, standard practice and turning to an alternate landfall.”

For all the many reasons we have already discussed ad nauseum, I don’t believe that AE and FN were engaged in a photographic intelligence overflight (a la Sidney Cotton) over Truk Atoll, or anywhere else. For more about Cotton, please see Jeffrey Watson’s, “Last Plane Out of Berlin” (2002).

All best,

William

LikeLike

While it’s fresh in my mind, I just read Art Kennedy’s interview with Bill Prymak. At the end Art states that at her last radio communication with the Itasca she had at least 5 hours of fuel left. That’s about the time it would take to fly from near Howland back to Mili Atoll, I believe. At that point she WOULD be out of gas and she would then have to ditch the plane there as is described by the native witnesses. All supposedly without a word of distress on the radio, even though after she landed she somehow made several or many detailed distress calls which were picked up by various receivers. Art thinks she was ordered to do something like this. I just know I could cogitate about this for the rest of my life and never maken any sense of it. But it could have happened that way.

All Best,

David

LikeLike

I’ve just completed some research in which a warship of the New Zealand Squadron of the Royal Navy, HMS Achilles, reported overhearing Amelia state that she was: “Quite down, but radio still working”.

Where they were down it does not say, however, this would seem to be evidence that she did make it to land and did not crash into the sea.

I’m not sure I buy the Truk overflight theory, but I can believe an operation to fake an emergency landing so that the US Navy could gather intelligence.

As with all her messages no position is given, and so one does wonder if this was deliberate in that whoever was in on the mission would know exactly where she was, or at least where she was supposed to be without her having to say it.

LikeLike

This is first time I’ve heard that Achilles received such an alleged message from the Earhart Electra. Please direct us to your source, or if unavailable online, perhaps copy and past it here.

Thanks,

Mike

LikeLiked by 1 person

The reference comes from the 23 July 1937 edition of Pacific Islands Monthly https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-312693846/view?sectionId=nla.obj-328747281&partId=nla.obj-312710382#page/n3/mode/1up

I’ve managed to obtain a copy of Achilles log for 1937, which confirms her movements, however, the radio logs were destroyed some time ago. It is unclear what the source is for the article, but since it’s a direct quote it may have come from the original logs at the time.

I’ve seen copies of the messages relayed to the US Navy and the Itasca from HMS Achilles but it is possible that the full details were not relayed. I have found no evidence that the message “Quite down, but radio still working” was relayed to the Americans.

I’m also trying to obtain copies of the radio log for the New Zealand Star, an ocean liner of the Blue Star Line that also reported hearing some of Earhart’s transmissions.

LikeLike

Thanks so much! This is very interesting, first time I’ve seen this report. For those who want to see it, it’s on p. 7 of the linked issue of Pacific Islands Monthly. It’s too bad the radio logs of Achilles are gone, but it’s quite likely that the logs are the source for the report.

Very nice find!

Mike

LikeLiked by 1 person

I may be hallucinating here, but I seem to remember in that disparaged British book about the British connection, wasn’t this incident with the Achilles mentioned? I probably threw out my copy long ago. Just thought I’d mention this in case I am right.

LikeLike

ON pages 76, 91 and 92 of J.A. Donahue’s The Earhart Disappearance: The British Connection, he makes references to a message received by the Achilles that was “censored” by the U.S. Navy, but never spells out what the message was.

On page 92 he writes, “When the Commodore commanding the New Zealand Navy, who was aboard the Achilles for the trip to Honolulu, learned about this radio intercept, he undoubtedly, having been told that there were two ‘birds’ in the air (one of them British), interpreted the exchange to mean that both parties were down and safe and hastened to spread the ‘good news’ to all concerned.”

“Two birds” safely down. This is only hint about what the message contained. Otherwise this book is nearly unreadable in its incoherence.

Mike

LikeLike

It isn’t difficult to understand why the US Navy might censor what HMS Achilles’ reported overhearing since this ran contrary to the official conclusion that she crashed into the sea.

LikeLike

David,

We can’t have you cogitate on this for the rest of your life and not make sense of it. So, let me offer this suggestion. First, start this or any other inquiry or investigation at an indisputable known point. For us, that’s the Electra on Barre Island, Mili Atoll. It had to get there somehow. And this is the point where we start “walking back the cat.” As we are all well aware, there are any number theories to explain AE and FN’s disappearance and the Electra on Mili — from the sublime to the absurd. It’s just a matter of separating the plausible from the implausible and seeing what fits with other known facts.

We must also always be on our guard so as not to be mislead by peddlers of false testimony. Additionally, don’t focus exclusively on AE and FN to the exclusion of all other things. Understanding the military, diplomatic, political, and cultural aspects of the time — the “big picture” — will assist greatly in putting all into proper perspective. It can be frustrating and daunting, but with patience, persistence, and dogged determination, we will eventually uncover the full facts concerning the why and how of AE and FN’s disappearance. Have faith, we will prevail, and to paraphrase Winston Churchill — Never, never, never, never, never give up!

All best,

William

LikeLike

William,

I was doing what you say already. I was in my garage attic today, just looking around for spare pieces of in my kitchen vertical blinds which I use as a curtain for my north facing double doors in my kitchen. I came across, lying on the floor, my forgotten copy of “Amelia Earhart: What really happened at Howland” by G. Carrington. I skipped over the beginning to arrive at the details of the flight. I see, though, it definitely sets the stage for the dire events of the middle ’30s and sheds much light on the problems FDR (and the rest of the Allies faced). I’ll get to that later today.

Anyway, I thought I would write some tidbits that surprised me. He does say that in 1937 the US had not yet broken the Japanese code. Maybe he means the military code, I think I have read that the diplomatic code was broken by then. The book goes into great detail about the operation of her radio(s). But nothing startling to us regulars. It does say on p. 142 just before midnight a call was heard by the Achilles on 3105 KC saying “please give us a few flashes if you get us.”

Then there is the mystery telegram to G. Putnam from George T. Huxford saying “Earhart had been picked up by a fishing boat west of Howland.” “Noonan was not with her.” and “When picked up she had been in a small boat.” (p. 147) I never heard of this.

Carrington has the pair flying over Truk at sunset I think, then they overflew Kwajalein in the dark where Noonan was experienced enough to be able to pick out military installations with the help of flares. This, of course, is not that badly written book which was ridiculed on this blog a few months ago.

Anyway I will post new tidbits if I find any in this 1977 book written bya British military man. Maybe all this is old news but I don’t recall Mike writing such details.

Stay Tuned,

David

LikeLike

Dave wrote “Then there is the mystery telegram to G. Putnam from George T. Huxford saying “Earhart had been picked up by a fishing boat west of Howland.” “Noonan was not with her.” and “When picked up she had been in a small boat.” (p. 147) I never heard of this.”

The fishing boat pickup report is well known, but for me at least, not this telegram for George Huxford you cite from Carrington’s book. I was told this book was not worth the paper it was printed on and I don’t even have it. Based on your report, I’ve decided to get it.

Mike

LikeLike

Another tidbit from Carrington p.148. July 6 Earhart’s radio transmission indicated the Electra was “floating but sinking lower in the water, very wet” “281 miles north.”

With my high school math, I figured the empty auxiliary tanks alone would float the plane. But, if there was any way the tanks could take on water, and they might have, eventually the plane would sink, of course. We would have to take an L10 and try an experiment to see what would actually happen. To me, this message gives an accurate description of what a water landing would be like.

How the radio would keep on working as the fuselage slowly filled with water, I don’t know. Maybe they had an emergency radio they could throw in a raft, for if they had to abandon the plane for a raft they would need one to keep on transmitting days after July 2. Yes, the stories contradict each other, raft or landing on reef, or if they wound up in the sinking plane it might have drifted north but it would hit Knox before Mili.

I did notice on my map that Mili is more westerly from Howland than north,so they could have been heading to Makin Island in the Gilberts, so says Carrington. Of course he does a lot of speculating like everybody else at some point. . One thing he does which is handy, he gives a running account of what was going on in the run up to war in the Pacific and Asia. I can see now that the situation in 1937 was much more alarming than I realized.

All Best,

David

LikeLike

So, I turned to page 149 of Lost Star which describes AE’s turn back to the Marshalls where she came from…… This makes no sense, Brink’s version describes an overflight of the Marshalls, very dangerous to try, she got away with it and now she is supposedly heading back there to save herself? Back to certain capture by the Japs and a very dim outlook for her and Fred? Did Goerner think she did this U-turn?

But, reading further, Brink tells of her radio messages of her capture certainly by the Japs and these messages were picked up by Hawaii and McMenamy and others. I thought her messages were regarded as fakes or at least doubtful. Then, supposedly FDR and the US government could not reveal they knew she was captured because that would tip off the Japs that their code had been broken? Why not confront the Japs with the reports from several operators that they heard her describe herself being captured by the Japs at some island controlled by the Japs? Maybe nobody at the time knew exactly which one, but didn’t McMenamy and other listening stations publicly announce they heard her describe her own capture? This is news to me. Or is Brink wrong?

Brink doesn’t mention Taroa, but my last comment shows my take on her predicament and right now, I think my Taroa overflight idea makes sense.

In my link there is a comment by Woody Peard about the Taroans taking pieces off the wrecks and selling them for scrap metal? They are risking their lives supposedly negotiating unexploded bombs for a few bucks? Maybe they are, but didn’t Woody or anyone ever search for the one wing plane that might be hers? The aerial photo shows where it is in relation to the runways so it should have been easy to find. I have never heard the possible identity of said one wing plane which must be still right there. I emailed Woody a couple years ago but got no reply.

All Best,

David

LikeLike

Hello David. Most of the UEXOrd on Maloelap was cleared by Steve Akin in the late 70’s, the same who took a Zero from Taroa and fiber-glassed the holes and shipped it to Saipan for his front yard. Recently another team cut open more recent ammo finds to make Maloelap safer. So not hard to walk around, I have done it many many times. The AC Boneyard, also documented by a series of photos in the Bishop Museum in Hono, was a mess of leftover AC debris, later added to when Steve bulldozed more of it into piles on the NW side of the main runway. 1 1/2 Zeros were also collected and eventually brought to Majuro, sold, impounded, court case, sold, and went to the Sterling Bros in Idaho then sold again, and a BEAUTIFUL A6M rebuilt, last seen sans engine.

Sorry, no AE Electra wing found. Woody has this theory her AC or maybe a rare IJN flying boat is buried in a concrete bunker on the NE shore area, but I’ve never seen it, and digging up ALL of Maloelap would be quite a task! I did find the AE Electra by the way! Well the one Brink describes and shows in a photo in his book from an USAF aerial shot, I actually sat in it and photographed it, it is the remains of a Mitsubishi G3M Neil. Same exact spot outside the triple revetment. EASY TO FIND? Buddy, It could be in the grass in front of you and you would never see it on Maloelap, or under the sand at Mili, or in a warehouse at PIMA (or the burned one in Saipan? haha), and you may never see it.

Maloelap is a living museum, you could spend a MONTH there with a team of 10 and never catalog everything. Plus, very simply, the locals have been promised WWII history tourism for decades, it never happened, and now very simply,, and yes sadly for me too, they are cutting up all the copper and alum and selling it for scrap and cleaning their land to the beauty it was before the horrors of WWII. Horrors buddy. Bombing and starvation and death. Come on over. I can take 3-4 pounds off your body in a day of walking the jungle. It is amazing. But it is not easy. OH, please bring your checkbook…its not cheap either.

LikeLike

Matt,

THanks very much for clearing up this mystery for me. Brink has quite a tale about the one wing plane wreck on Taroa icluding the Jap commander’s two seater Zero which apparently didn’t exist. Maybe other participants here wondered as I did whether this one wing plane was ever positively identified. Now it has been. What was the purpose of bringing so many wrecks to Taroa instead of leaving them all where they fell? It must have been a whole lot of work. Was it to have a junkyard for spare parts?

My only experience with a plane wreck was finding the DC3 on Mt. Success near Berlin, NH a 1954 wreck. If I had not known what it was, I would have had a very hard time identifying the plane. I would have thought I would see the engines, but they weren’t there. I think maybe they were salvaged for parts long ago. Where I woud find any tag or plate telling me what kind of plane it was, I had no clue. Of course I thought of Billing’s wreck on New Britain and what a chore it would be to find a wreck in the jungle. Occasionally on my hikes in the forest I come upon the wreck of a car and it’s about impossible to figure out what brand they are and how they got there, the trail must have been driveable with a car decades ago. So I can kind of see what you mean finding those wrecks would be very hard work.

Carrington, in his book, is really gung ho for the spy flight scenario. I do question what purpose it would serve 4.5 years before the war. But then again, why did the US Navy finance her flight? Just to make AE and Putnam lots of money? Probably not.

Also, if they were just innocently lost somewhere north of Howland and they decided to fly west to Makin Island in the Gilberts and they slightly miscalculated and wound upon Mili Atoll, why did the Japs seem initially to buy their story and then later change their mind? What did they discover that would lead them to believe she was spying? They developed the film in her camera(s) and found she had flown over Truk? That would be enough to motivate them to lock her up. As I have said we should know the answer soon after Biden gets in so we don’t have long to wait, do we?

All Best,

David

LikeLike

Hi David.

Here are some short answers. 1. Maloelap was major hub and had major losses on the ground and flown in war wearies for repair, thus the boneyard. There is also a boneyard of debris out in the lagoon also. 2. Woody’s 2 seater A6M FLOAT PLANE zero for the commander is also pretty far fetched. I have a translation of the last Commanders diary and there is no mention of it, BUT a mention of Zamporini and some whiskey being shared, which I mentioned to Laura, but due presumably to her illness, she could never research herself. Woody claims the AC in a concrete bunker. Brings lots of big guys, big hammers, lots of shovels, and some $$ to pay the workers and the Iroij (King) for his permission, and he will probably need it for his legal defense fund…as Cocaine washed up on Maloelap and now the scourge of Majuro….

3. All modernish USA AC have casting and stamping numbers, which make AC ID pretty easy. The AC engine on the reef N of Taroa I initially reported as from a B-25, as per assorted ACLossReports, but in fact, was from a PBY AND had a Ventura junction box to make it complicated. So more sources out there when you find a debris field. 4. Spy Flight. Well the “buried” canister on Mili probably didnt hold any camera equipment or film, but her collection of endorsed stamps and envelops she carried around the world. This was a secret search made by a team in the 1990s I was associated with.

After the typhoon of 1959>? the topography of that side of Mili changed, and the “tree” used as a reference point disappeared. Bring more metal detectors/shovels/workers/$$$. 5. Makin. Please don’t call it Makin if you mean Butaritari. Makin is a little tiny atoll, most error USArmy records called Butaritari Makin. Ops. Mistake US Army. But it makes me crazy. USMC 2nd Raiders stuck BUTARITARI in Oct 1942. Black and White Movie PR followed. Killed almost all the Japanese resistance, including the ones in the H6K sunk while landing. Marines didnt know that.

Butaritari is a wonderful place to visit. LOTS of history, all sources. Even Bars during Robert Louis Stevenson book time, its in there. Henry Muller hid a US Marine in his cookhouse the first night. The Marines were traumatized trying to exit via the NASTY surf multiple times, and yes, I believe they tried to surrender that night, but they killed the messenger! When the sun came up calm was restored. The Gilbertese policemen alerted the Japanese, not an errant rifle shot, btw. There is a sad piss poor concrete chicken scrawled “monument” at the site of the KIA Raiders excavated by CILHI/JPAC.

6. I have always thought she force landed at Mili and was well taken care of (by the 6 Japanese weather/customs/tax guys), but when she got to Jaluit, well the world changed. Then she was stuck, spy or not, as her eyes saw way way too much. 7. Last. If AE had done a proper fly over Nauru and the radio station there, she would have had a much better chance to hit Howland, her mistake in not getting the station to verify their hours and frequencies. And that’s my lunch conversation, time to go back to work. I have photos to back up most of what I have seen, ask, I can provide Mike. Let the mystery continue!!

M. Holly.

LikeLike

Very interesting and thought provoking comments and discussion. I tend to look at the whole idea of an intentional overflight of the Mandates (no matter what theorized route) to be highly unlikely and impractical. While such a flight might have been possible, what would really be gained by it?

Given the known parameters of the Lockheed 10E aircraft and an already long direct flight from Lae to Howland, to add extra miles and hours for a few possible snap shots (weather and sunlight permitting) would have been extremely dangerous and fool hardy. This was in the days before autopilots and crew fatigue would have played a major part in any scheme to lengthen the flight. And the longer the flight, the more chances for something to go wrong.

The idea of ditching a land plane in the vast Pacific for the sole reason of giving the US Navy an excuse to conduct a SAR mission is something no aviator would even consider – especially one who wanted to set a new world aviation record. The Navy would not have needed any such disaster to initiate SAR operations. If they wanted to conduct such a mission, they could simply state that one of the Navy planes had gone down in the area on a training flight.

If an espionage flight over or near the Mandated Islands was needed or desired by the United States in 1937, the US Navy could have flown it far more successfully with a Consolidated PBY Catalina. The PBY was a flying boat which could take off and land on the water. It was slow, with a max speed of 175 MPH, but had an endurance time of 24 hours and a cruise range of 2,350 miles. In October 1935, the PBY prototype made a nonstop flight of 3,500 miles.

PBY’s were being used in New Guinea for civilian scientific exploration, so maintenance support would have been available there for a long flight. The PBY could land on the water and be refueled from a US Navy Seaplane tender if necessary. But simple “out and back” flights by a Patrol Squadron attached to Guam could have provided any needed flight reconnaissance of the area.

With a more suitable Navy plane available, why would anyone even consider trying to do a military mission with Amelia’s Lockheed 10E?

That said, consider the Japanese side of things. Of course they had begun military build up of the Mandates, although still claiming that any work done there was for civil improvements and for benefit of the islanders. If an aircraft was to land on or near one of “their” islands they would have probably considered it an act of “spying” – regardless of what anyone would say to the contrary.

There are many theories as to how Fred and Amelia could have ended up on/near Mili atoll. The most reasonable one would seem that they were off course and unable to make contact with the Coast Guard Cutter Itasca. Without a trailing antenna on the aircraft, the Itasca could not obtain a bearing on Amelia. Unable to pick up transmissions from Itasca, Amelia could not obtain a bearing on Howland/Itasca.

What was available that morning to navigator Fred Noonan was the rising sun from which he could obtain a “speed line”. That is a line that would indicate where he was on his projected course. It would not, however tell him if he was right or left of course. Projecting his progress based on his airspeed from that sun line to Howland on his chart, he could determine their estimated time of arrival (ETA).

When that time came, and Howland was not in sight, a proper procedure could have been to turn left or right 90 degrees to course on the chance that they were left or right of their intended course. This is probably what Amelia was referring to when she said that she was “On the line of position 157-337” and “running North and South”.

It is very possible that they were initially further north of Howland than they thought and spent some time in their “North and South” flying before giving up on finding Howland – just not flying far enough South to see Howland. At this point, she flew West, hoping to find a suitable alternate site in the Gilberts to land or ditch. Unfortunately, being further North than she thought, it was the Marshalls that she encountered, choosing to land/ditch at Mili Atoll before fuel was exhausted.

If their original flight plan included a slight deviation to overfly the Gilberts or Marshalls, then they would have had interim visual fixes of where they were by comparing sighted islands with the islands on their chart (map). Finding Howland would have been made easier if the Gilberts were overflown.

It is very likely that if Fred and Amelia were picked up by the Japanese, there would have been much radio traffic about them – at first in the clear from boat to ship or island, and then later in coded long range transmissions to other islands and to Japan. A reason for US Government secrecy may very well have been due to the need to keep our code breaking capabilities or information about human agents in the area secret.

LikeLike