Conclusion of Goerner’s interviews with Joe Gurr

We continue with the conclusion of our retrospective look at the Amelia Earhart Electra’s radio capabilities via interviews of radio expert Joseph Gurr by Fred Goerner as compiled by researcher Cam Warren and appearing in the February 1999 issue of the Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters.

Fred: “[Are} 9.3, 15.45, and 21.7 mc that you referred to back in 1937 as being the ranges or the capabilities of that Bendix direction finder that was in the aircraft [considered] pretty high frequencies?”

Gurr: “Oh boy, I tell you it was. Initially those frequencies were not used too much. Today, they are commonplace.”

Fred: “Where would 7500 [i.e. 7.5 mc] fit in there?”

Fred Noonan, circa mid-1930s, in his Pan Am uniform. In March 1935 he was the navigator on the first Pan Am Sikorsky S-42 clipper at San Francisco Bay in California. The following month he navigated the historic round-trip China Clipper flight between San Francisco, California and Honolulu, Hawaii piloted by Ed Musick (who was featured on the cover of Time magazine that year). “I don’t care what kind of equipment she had in that airplane,” Joseph Gurr told Fred Goerner, “She did not know how to use it. Noonan, hell, he didn’t know nothing as far as I’m concerned!”

Gurr: “Oh, that would be wonderful. That is one of the real good ones. That is what you call the 40 meter band. It is a real good general band. Day time, up to a thousand miles generally with relatively low power. At night, you can whip around the world. Again, it is subject to a certain amount of skip.”

Fred: “[Was] Amelia capable of sending CW [Morse Code], or was Noonan capable of CW?”

Gurr: “I don’t know about Noonan but I don’t think Amelia was.”

Fred: “That is why she never made any attempt to use it?”

Gurr: “I was really concerned. In using the radio direction finder; that is if you are homing in . . . if [you] haven’t got a range and you want to work a problem, you have to know at least an “a” from a “n.” I’m sure she didn’t know the code. As far as Noonan is concerned, I don’t know.”

Fred: “Unless Noonan was in the cockpit, he couldn’t have worked any radio anyway, could he?”

Gurr: “No. The way the thing was set up, we had a key — oh, about that key. Now, let me see if I can think about that once. We had a key installed on the navigator’s table in the back. It was installed when I got into the picture. The idea was that you would send code. Code gets out far more distance. That was great, but then, I have a very hazy recollection that that key was removed. I don’t remember just when, but some place along the line, I heard that they had removed it. It might have been in Florida. Nobody knew the code anyway.”

Fred: “Manning did. It was there to begin with and I suppose it was there for him to use. Neither Amelia or Noonan knew how to use it then?”

Gurr: “That was it then.”

Fred: “It was of no use to them anyway. They were going to depend upon their 3105 or 6210 channels, and their direction finder.”

[End of radio remarks. The balance of this interview discusses various people such as Vidal, Miller, Pearson, et al.]

[PART TWO: Interview recorded Aug. 14, 1987]

Gurr generally concurred with his earlier story. He reiterated his fondness for the [direction finder] that “the Navy sent out,” again remarking that “the receiver was an all-band job” that “they can even listen to ham radio on this one.” (Later in this interview he enlarged on the statement, saying “it went from 200 to somewhere around 15,000 kc because it also covered the 20 meter amateur band, which is 14,000.”) (If he recalled correctly, this would likely indicate the [Bendix] receiver covered five bands, as did the RA-1B.)

Gurr felt the equipment was fine, but had reservations about the operators. “I don’t care what kind of equipment she had in that airplane, she did not know how to use it. Noonan, hell, he didn’t know nothing as far as I’m concerned!” Gurr told Amelia that she didn’t have much transmitting power, but to use 6210 during the day, 3105 at night, and “just press the button. Just say, ’Itasca, this is me!’ Just press the button and Itasca would get a bearing — assuming that the Itasca had the equipment and that they knew how to use it far better than Amelia Earhart. That was the answer to the whole thing — they would give you a compass heading to take, and you’ve got it made.”

Amelia Earhart with Harry Manning (center) and Fred Noonan, in Hawaii just before the Luke Field crash that sent Manning back to England and left Noonan as the sole navigator for the world flight.

Harry Manning had Gurr’s full admiration: “He was good. He was a nice guy personally, but on top of that he was qualified. If he wasn’t, he wouldn’t be captain of a big ship like that [the SS America]. He was really good. I thought, [Amelia] you’ve got it made. I hate to go on record to say this, but when Noonan showed up — aw, golly!”

“I don’t know but there was just something that happened to all of us [in Burbank] — to

everybody around there, all the people that were working around on the airplane. Like, if I may say this, the reputation he [Noonan] gave Amelia, and that caused her to take him, was that he was the original navigator for the original trip of Pan American to fly over the Pacific and so on. Well, I immediately said, ’O.K., so how come he is out of a job now?’ In those days, we were using navigators. United [Airlines] was using navigators on their trips to Honolulu. In fact, we don’t anymore, but in those days that is how it was done. Navigators were — heck he could get a job anytime; I’m sure he could. Something happened fight there. I never talked to Amelia. I never talked to Noonan. His reputation as a man who imbibed a little once in awhile came with him.”

Earlier, Goerner had asked Gurr that, considering the radio installation, if it would have been possible to use the transmitter if the plane was afloat in the pacific. Gurr said he knew the plane wouldn’t sink for awhile “if they could somehow dump those big motors.” But the transmitter would operate “especially for a little while. They couldn’t do it for long because now your engines are stopped and you are running on storage batteries. It takes power. Now let us say, under some conditions, if she was able

to land that airplane so that it was floating, even for 5 or 10 minutes, yes, she could transmit because the antenna was in the clear and the transmitter was not in the water because it was up pretty high. You know, above the navigator’s table. Now this is all an assumption. If the airplane was floating at all, yes, she could transmit. She could really get on that mike button and really transmit.”

Amelia Earhart at the controls of her Lockheed 10E Electra before taking off from New Guinea, on July 2, 1937. She disappeared the next day. (National Archives)

Fred: “How severe would the drain be on those batteries if she were trying to transmit on 3105 or 6210?”

Gurr: “Not severe. It was not that big a transmitter. They were 12 volt batteries, and I would say, [the transmitter would draw] probably 10 amperes when she pressed the button. Ten amperes would be about right. I never measured it.”

Fred: “So you would have what? In terms of amount of time available from those batteries.”

Gurr: “Oh, she could transmit for an hour off and on. But, if that airplane was afloat, it wouldn’t be afloat for long. It wouldn’t be afloat any three days; those engines would pull them under.” And further, “I can conjecture what could happen to Amelia’s airplane. I knew the airplane, all those big tanks, the heavy motors and the skill. Not only that, I know the Pacific Ocean. A lot of people seem to think that it is a big flat pond. It isn’t. It’s always rough out there. And you take waves 5 or 6 feet high with little white caps and you try to land an airplane in that, and believe me boy, you just hop, skip, and so on and finally you just plunk! If you did a good job with your gear up.”

End of “What Radios Did She Really Have?”

Goerner interviews radio expert Joe Gurr, Part II

We continue today with Part II “What Radios Did She Really Have?” our retrospective look at the Amelia Earhart Electra’s radio capabilities via interviews of radio expert Joseph Gurr by Fred Goerner as compiled by researcher Cam Warren.

In answer to Fred’s query as to how Amelia got this “Navy gear.” Gurr replied: “I asked no questions.” Fred showed him several photos of the plane “passed by Navy censors.” They clearly showed the topside antenna mast and the loop, “and some of the gear below.” Gurr confirmed that this showed the configuration after the rebuild.

Fred: “Right after the disappearance, newspaper accounts ’mentioned a Joseph Gurr, Burbank engineer, who installed the sending apparatus.’ Then [the story] quoted you as having said: ’9.3, 15.5 and 21.7 mc.’ What does that mean to you?”

Gurr: “She could receive [those] frequencies on the Bendix gear, but not transmit on [them].”

Fred: “To get a heading from the Bendix Direction Finder? She would receive on those frequencies?”

Gurr agreed, saying: “This was high frequency. It also had the [2-400 kc band]. [I’m afraid I didn’t stress to Earhart] the value and usefulness and that gear. Oh, it was wonderful!”

The Bendix RA-1B, used in Amelia Earhart’s Electra during her final flight without apparent success, was a brand-new product and was reputed to be pushing the state of the art in aircraft receiver design.

Fred asked if Gurr thought Fred and Amelia knew how to operate it property. The reply was only a grunt.

[There following a discussion of the gasoline load, then the subject returns to radio].

Fred: “Why was it do you suppose that Amelia never broadcast on 500 kc? All during the flight on which she disappeared, she never once broadcast on 500 kc. The Itasca had a 500 direction finder. The Navy had sent a 3105 direction finder down from Pearl Harbor and installed it at Howland Island. She kept broadcasting on 3105 and asked the Itasca to take a direction on her on 3105. The Itasca kept asking her to broadcast on 500 and she never did on 500. Why not?”

Gurr: “There might be a number of reasons for that. At 500, I never was able to work anybody on 500 when I was working on the equipment. That was only here locally. 500 kc is a very, very low frequency and you have to have power to get out at all. [She had] her little 50-watt transmitter and a reduced size antenna. On 500 kc you want to have a proper antenna. On sea-going ships, they have these great big antennas between the masts that are separated by quite a distance and they have a lot of wire out there. That is what you have to have. On an airplane where she did not have much of an antenna, her range on 500 kc was very short. If she was, let’s say in sight of a ship, she could talk. As I recall, we talked about that very thing. If she was in an overcast and she raised a ship, she could be sure the ship was not very far away. In reading your book, I think you explained it very well. She did not stay on the air long enough for the Itasca to take a beating on her. In those days we didn’t have the automatic features. We had to do all of this manually. The radio operator on the Itasca would tune the signal in, then he had to rotate his beam to get a null and I don’t think she ever talked long enough for him to do that. They kept asking her to send ’A’s. All they needed was that carrier.”

Fred: “She asked the Itasca to send ’A’s on 7500.”

Gurr: “That means she was using that Bendix machinery. On 7500 she could have heard that if the Itasca had any power at all, even 2[00] or 300 watts. They could transmit a good signal for several hundred miles.”

Fred: “At one point, she said, ’we are receiving your signals but cannot get a minimum.’ What did that mean?“

Gurr: “That means she was turning the loop and could not get a null.”

Fred: “Because of what? The signal was too weak?”

Amelia, with Bendix Corporation rep Cyril Remmlein, and the infamous direction finding loop that replaced Fred Hooven’s “radio compass” or “automatic direction finder.” Hooven was convinced that the change was responsible for Amelia’s failure to find Howland Island, and ultimately, for her tragic death on Saipan. Whether the loop itself failed the doomed fliers during their final flight remains uncertain. See p. 56 Truth at Last for more. (Photo courtesy Albert Bresnik, taken from Laurance Safford’s Earhart’s Flight Into Yesterday.)

Gurr: “There are many reasons she could not get a null. As an example, unless you have a considerable number, a quite strong signal, nulls are not easy to find. If the signal is weak, you can go through a null. You have to have a solid signal. Then too, in those days the equipment wasn’t developed like it is these days. State of the Art is quite different.

“In those days, a little static — maybe she was excited, flying the airplane and trying to tune the set to get the best signal. She might have had the loop turned more or less at the null. She should have had it straight forward, if she was headed toward Howland. Had the loop fore and aft to get the maximum signal. She had a sensing antenna which was that V-antenna and the idea was to first tune in the signal on that antenna and then switch it over to the loop and get a bearing.”

Fred: “This takes time.”

Gurr: “And it takes a certain amount of cool-headedness about that time.”

Fred: “The trailing antenna had been removed at that time?”

Gurr: “It was still on board. She did not use it on 500 kc. That was the object of the antenna on top. We put on all the wire we could, as much wire up there as possible, and to get it off the fuselage so that the fuselage would not have an absorbing or a reflecting effect. We were very successful. Actually she had as much wire as possible on that airplane. This was for transmitting. For receiving, you didn’t have to have that much. She had that V-antenna down there which was fine.”

Fred: “Apparently that was working very well because she checked back in with Lae, New Guinea 800 miles out on 6210 in the daytime.”

Fred: “There were messages that amateur radio operators said they had received after the time of the disappearance of the plane. They were received along the Pacific Coast. I have talked to a number of the operators and I believe they actually did receive messages. Would it have been possible to broadcast if they had been down in the water?”

Gurr: “Yes. The antenna was dear. If that airplane was floating, the antenna was up on top of the fuselage and she could transmit until that antenna was submerged.”

Fred: “Did she have batteries in the cockpit or something that would enable her to power her gear.”

Gurr: “Storage batteries, yeah. There was a storage battery generator. In flight, the generator was charging the batteries. In those days, airplanes carried decent flight batteries. I don’t remember how many she had, but I know she had at least one. Flying along as she was, that battery was probably well charged. Then, supposing she was down in the water, and got on the air to transmit, she had the power. The transmitter itself did not take an awful lot of juice. It was a low powered transmitter. She could probably transmit for 30 minutes if the battery was fully charged. Intermittent, maybe longer than that.”

Fred: “Could 3105 be received on the Pacific Coast and not be received in the general area of where she went down?”

West Coast amateur radio operators Walter McMenamy (left) and Carl Pierson, circa 1937, claimed they heard radio signals sent by Amelia Earhart, including two SOS calls followed by Earhart’s KHAQQ call letters.

Gurr: “Oh yes. Especially at night. 3105 at night. It was daytime between here and Howland Island. It is very unlikely, but at night, yes. These frequencies are subject to a certain amount of skip and the higher frequency you go, the more that skip.”

Fred: “And not be received by a vessel in the general area?”

Gurr: “That’s right.”

Fred: “This Navy direction finder, the 3105 that the Navy Dept. sent down on board Itasca to use in conjunction with the flight evidently was a rather hush-hush model at that time. They were experimenting with high frequencies, through a department and the Navy known as OP-G20, which was Naval Intelligence Communications. You know anything about development of high frequency direction finders at that time?”

Gurr: “Only things that were published. I had no connection with the Navy or any military organization so far as any of the classified developments. We knew in the airline business and especially being interested in radio as I was then, I knew pretty well what developments were upcoming. We knew the limitations of the low frequencies. We knew that we had to have something better. Obviously the experimentation had to go to the high frequencies. At that time there was a feeling that the high frequencies had a tendency to bend, the waves would bend and would get a false radio direction finding. Maybe that was true in certain locations, certain altitudes and so on. This was all subject to experimentation. That was brand new stuff in those days. Now, as you know and we know, the military is always researching, developing and working on projects. Now-a-days, they call it classified, or secret. You never stop.

“Obviously the Navy had classified gear then. And they have it now. The 3105 [kc] radio

direction finder was considered a pretty high frequency to get a reliable direction, at that time. Today, we know its limitations. We know what it is doing. The airlines now have fully automatic units that lock on to the beam and take it right down the line. In those days, we thought 3105 was getting into rather high frequency.”

(End of Part II.)

Goerner’s interviews with radio expert Joe Gurr

Between 1970 and 1987, on at least two occasions and possibly more, Fred Goerner interviewed Joseph Gurr, a flight dispatcher for United Airlines in 1937 and a radio expert who “volunteered” to help Amelia Earhart with her new Electra’s recently installed radio equipment at some unspecified date prior to her first world flight attempt in March 1937.

Earhart researcher and Amelia Earhart Society member Cam Warren compiled the following excerpts of the Goerner-Gurr interviews, and the following article appeared in the February 1999 issue of the Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters. This is the first of three parts.

Joseph Gurr was a flight dispatcher for United Airlines, Burbank, in 1937. Station Manager John Kimball was his boss and, according to Gurr, he was “a distant cousin” of Amelia. Kimball was also a good friend of Paul Mantz.

Earhart had just returned from New York with her new airplane, where Bell Labs had “worked on“ the radio equipment. However, Amelia had not been able to communicate with anyone, nor pick up the radio ranges on the trip. Gurr had radio experience, so volunteered “I had a day off, I think the next day, and I went out there in the morning and found all sorts of little simple things like somebody forgot to connect the antenna lead, and the receiver didn’t work. I connected it and it worked. Then I thought if that is the way it is, maybe I’d better check the whole thing over. It was probably all O.K. except for simple things.”

This was a couple of months before the first attempt — the abortive flight to Honolulu. Gurr met Harry Manning, and got to know him quite well. “He was a ham radio operator — he knew the code. Obviously, he was a navigator of the first order. He was the captain of a very fine ship [and] he was a gentleman of the first order.

In the only photo of Joseph Gurr I have in my files, we see Amelia with Gurr at Burbank, Calif., before her second world flight attempt in June 1937. Interviewed by Fred Goerner in 1984, Gurr said he had constructed a new top-side antenna on Earhart’s Electra that could be used in a forced landing as long as the storage batteries and transmitter remained above water. Other experts disagree.

“He was very thorough — as an example [Earhart’s] safety equipment. I will never forget the day he rolled all of it out on the apron. All the safety gear they were going to use; life-rails and all the various things we had in those days. A kite — we even flew the kite. The fellows in the hangar thought that was pretty silly. . . . This man was steeped in safety as the captain of his ship, and he was testing this gear out. I’ll never forget that — and I helped him. I was taking gear out of the airplane and going through it with a fine-tooth comb.

“For an antenna, [she] had this trailing wire. I’ve had some experience with trailing wires. In those days, a nice long wire was very efficient. . . . [But] there were difficulties. . . . You forgot to roll the thing in, you come in for a landing [and] you wrap it around power wires. Or the weight, the big lead weight there on the bottom, would fall off and kilt Mr. Jones’ cow. We had all sorts of problems. . . The airlines . . . wouldn’t use it. I questioned [that antenna] right away and they told me that is the best thing they have on the airplane. I let it go.”

Paul Mantz, accompanied by Gurr and Manning, made numerous test flights with the Electra, frequently traveling as much as 500 miles out to sea. Gurr was impressed with Manning’s navigation: “There was no question about it — with a man like that on board, you didn’t have to have a radio. In those days, radio wasn’t very reliable.” But Manning was capable with electronics too, experimenting with the trailing wire antenna, running it in and out until he found the length that provided the best performance. “There wasn’t much power [available from the Western Electric transmitter, but] it could still get out 50-100 miles.”

The first attempt by Earhart, the east-west course, saw her ground-loop the plane in Honolulu. The Electra was returned to Lockheed for a rebuild. Gurr stated: “I took all the radio gear out and took it home. All that was involved there was to check it out. I just simply went through everything with a fine-tooth comb. I made quite a splash about their antenna system. The [Lockheed] had an antenna that was about 2 inches off the fuselage. Obviously, you are not going to radiate much power that way. I went to work to put a stub up forward at least 18 inches high. As long as the airplane was in the factory, they didn’t want to do it. In order to do that, they would have to do a lot of engineering work and would have to be beefed up under the skin. [We] had quite a bit of discussion. [If] you get that antenna off the fuselage, and build a V-type antenna, put a lot of wire out there, run a wire to each tail fin, why then we don’t have to rely on that reel. Then, we could tune the transmitter to that antenna.”

This photo of Josephine Blanco Akiyama with Amelia Earhart’s technical advisor Paul Mantz appeared in the June 1, 1960 issue of the San Mateo Times, with the following caption: “CLUES TO Amelia Earhart’s fate were examined in San Mateo yesterday by famed pilot Paul Mantz, Miss Earhart’s technical advisor. In photo at left, Mantz examines documents with Mrs. Josephine Blanco Akiyama, whose exclusive story in The Times broke the case wide open last week.

Goerner then showed Gurr a copy of a letter from J. W. Gross, then president of Lockheed, in regard to the original radio equipment that had been installed on AE’s Electra. Gurr said, “This is rather accurate. I know that receiver and Western Electric transmitter. This Bendix — now that was nothing more than a radio direction finder. This particular receiver had one feature that was rather new; that was it operated on more than one bank of frequencies. The old ranges were on [200] to 400 kc and the airlines had receivers that just tuned that. In this case, it not only had that particular band but it also had other [higher] frequencies, which was a very good thing. Then, and I tried to put that point over, she could tune in a broadcast station at night in Honolulu, [and home in on it]. It was a sensitive receiver. It was a good one.

“The radio compass, as he said, was installed elsewhere. It was not installed at Lockheed. None of this gear was installed at Lockheed as far as I know. Unless it was installed before she went east and came back again. Now that is possible. I know that Bell Labs in New York worked on it. The transmitter? About 50 watts. You could get that.”

Fred: “You said you had some changes made. You had the trailing antenna removed and the V-antenna put in. I showed you the repair orders from Lockheed that have your name on them.”

Gurr: “Yeah. This V-antenna. The purpose of that was so we would have an auxiliary receiving antenna in case she lost the one up above. They felt that, this is so much wire, if something should break, this way we have two [antennas]. So they installed that V-antenna underneath, which was similar to what we were using in the airlines.”

Fred: “You really didn’t need the trailing antenna at that point?”

Gurr: “No. In fact, having had airline experience, I just did away with it.” [Seventeen years later — 1987, Gurr denied removing the trailing wire. When Fred said “. . . there are people who swear up and down that it was removed in Miami.” Gurr replied: “Yeah, that is probably more true.”] (Italics TAL editor’s.)

Fred: “There have been those who said that Amelia had the trailing antenna removed because it was too much trouble for her to reel it in and out. Actually she didn’t need it. You had advised her that she didn’t need it.”

Gurr: “’I didn’t think it was a good idea. For one thing, it was too hard to make work. The other thing is, they were mechanically very unreliable. If you were planning a long flight as Amelia was, I wouldn’t depend on any trailing wire.

Fred then quoted from yet another Lockheed work order: “Install necessary reinforcing for Bendix Radio loop compass. . . ”

Gurr: “Oh yeah, this is beginning to ring a bell. We had radio compasses but this was no radio compass [does he mean, “not only a radio compass”?] This particular Bendix radio receiver [RA-1 or prototype, perhaps]. I seem to feel that the thing was delivered to us, that we installed it. It was something special, delivered from the Navy Dept. It was a very sensitive device, but otherwise it was just a loop antenna. This Bendix to me, at the time, was the slickest piece of gear that she had on board. This was the thing that would take her around the world. All she needed to do was use 400 kc.”

Fred: “She kept asking, during the flight, for signals to be sent on 7500 kc.”

Gurr: “She could receive that on the Bendix. In the daytime, 7500 kc would be good — it would give her several hundred miles, sometimes even more than that. At night, under certain conditions, it is quite terrific.” (End of Part I.)

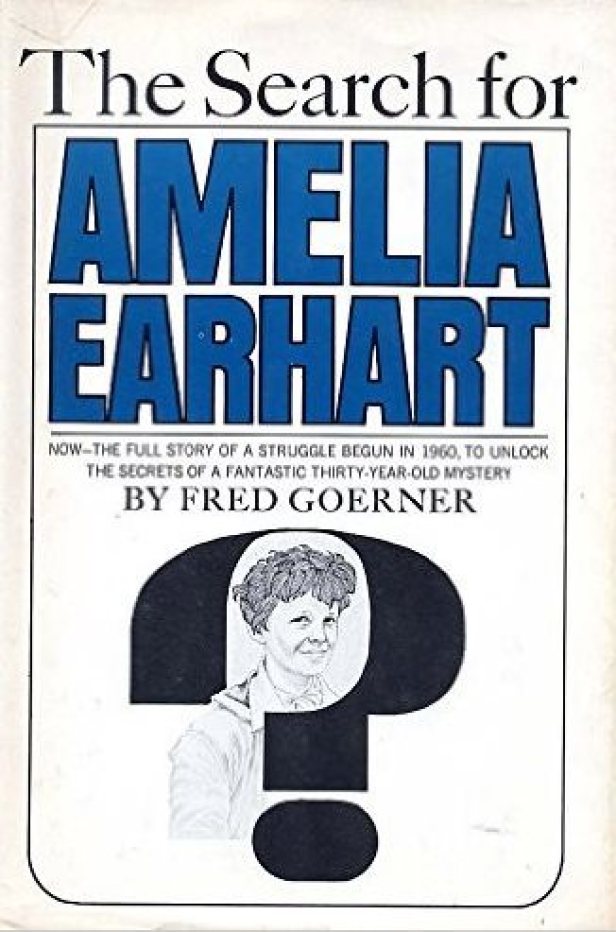

Fred Goerner holds forth in 1987 radio broadcast

The following monologue from former KCBS Radio newsman, pre-eminent Earhart researcher and best-selling author Fred Goerner appeared in the November 1997 edition of the Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters. It’s a snapshot of Goerner’s thinking in 1987, just seven years before his death from cancer in 1994. He’s clearly learned much since his 1966 bestseller The Search for Amelia Earhart was published, but he’s far from declaring, “Case closed,” and continues to speculate about major aspects of the Earhart case.

The radio station remains unidentified, but it was likely a West Coast outlet, since Goerner lived in San Francisco and spent most of his time there, and could have been KCBS, where he was a prominent newsman during his Saipan investigations of the early 1960s. Bold face emphasis is mine throughout.

“A Thorough Search for An Illusive Answer”

(Fred Goerner speaking on a radio broadcast in 1987)

. . . . I began the investigation in 1960, for the Columbia Broadcasting System. There was a woman named Josephine Nakiyama (sic, Akiyama is correct) who lived in San Mateo, CA who in 1960 stipulated that she had seen an American man and woman, supposedly fliers, in Japanese custody on the island of Saipan in 1937. My reaction to the story was one of total and complete skepticism. It seemed to me that many years after the fact, and 15 years after the end of World War II, that surely if there was such information, our government knew about it.

I was assigned by CBS to follow the story, and I was sent to Saipan for the first time in 1960. I have been to Saipan 14 times since then. I have been to the Marshall Islands 4 times. I have been to our National Archives and other depositories around the country countless times, in search of extant records that deal with the disappearance and with respect to Miss Earhart’s involvement with the US Government at the time of her flight.

This is the photo of Josephine Blanco Akiyama that appeared in Paul Briand Jr.’s 1960 book Daughter of the Sky, and launched the modern-day search for Amelia Earhart. She died in January 2022 at 95.

This [effort] has now extended over 27 years. You may wonder why I want to record my own statement. It is simply because there are so many people who have involved themselves over the years, for various reasons. When you present something, it often comes back to you in a different manner. [Therefore] I would like to have a record of everything that I have said, so that if somebody is trying to quote me, I can definitely establish what it is I HAVE said and what I have not.

Let me say at the outset here, that there is no definite proof — I am talking about tangible evidence here – that Amelia Earhart was indeed in the custody of the Japanese and died in Japanese custody. [However] there is a lot of other evidence that points to that possibility. [For example:] it was the late Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz who became sort of a second father during the last years of his life, who kept my nose to this story. He indicated to me that there were things behind it all that had never been released.

I wrote the book “The Search for Amelia Earhart” in 1966, and it did reach many people. People in Congress and in the Senate began to ask questions of Departments of Government who, up to that time, had denied that there were classified records of any kind in any of the department of the military and/or government that dealt with Amelia Earhart.

It was not until 1968 that the first evidence began to surface. At this juncture [1987], there have been over 25,000 pages of classified records dealing with Earhart’s involvement with the military. As a sidelight, I think it is a supreme salute to Amelia that, 50 years after her disappearance, we are still concerned with finding the truth where this matter is concerned. These records that have been released reveal clearly, unequivocally, that Amelia was cooperating with her government at the time of her disappearance.

The only bestseller ever penned on the Earhart disappearance, “Search” sold over 400,000 copies and stayed on the New York Times bestseller list for six months. In September 1966, Time magazine’s scathing review, titled “Sinister Conspiracy,” set the original tone for what has become several generations of media aversion to the truth about Amelia’s death on Saipan.

That does NOT mean that she was that terrible word, a SPY, although at one time we at CBS had suspected that this was a possibility. Particularly when we learned that Clarence Kelly Johnson, at Lockheed Aircraft, had been the real technical advisor for her final flight. Mr. Johnson later headed the U-2 program and our SR-71 supersonic reconnaissance program[s]. In conversations that I have had with Mr. Johnson, he has convinced me that Amelia was NOT on an overt spy mission.

The records do indicate, though, that Amelia’s plane was purchased for her by the (then) War Department, with the money channeled through three individuals to Purdue Research Foundation. There was a quid pro quo: Amelia was to test the latest high frequency direction finder equipment that had intelligence overtones. She was also to conduct what is known as “white intelligence,” but that [did] not make her a spy. Civilians very often perform this function for their governments. They are going to be in places at times where the military cannot visit. All one does is to keep one’s eyes open and listen. She was going to be flying in areas of the world then closed to the military. Weather conditions, radio conditions, length of runways, fuel supplies, all information that would be of interest to the military.

They asked her to change her original flight plan to use Howland Island as a destination, and it was to that island she was headed at the time of her disappearance. The United States was forbidden by the 1923 Washington Treaty Conference with Japan, to do anything of a military nature on these islands. Amelia was to be the civilian reason for construction of an airfield [there] that could later be used for military purposes.

At the Amelia Earhart Symposium held at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum as few years ago, I revealed that Thomas McKean, who is [was] head of Intertel [Inc.], had been the Executive Officer of the 441st Counter-Intelligence Corps unit in Tokyo after the end of the war. He had done the study for the CIC, and testified that a complete file was established at that time, [which included the information that] Amelia had been picked up by the Japanese and died in Japanese custody.

[Further] there have been over 40 witnesses on the island of Saipan who testified in the presence of church authorities. From them information was gathered that claimed a man and woman answering the description of Earhart and Noonan were held in Japanese custody on the island in 1937, and that the woman died of dysentery sometime between 8 and 14 months after her arrival. And the man who accompanied her was executed after her death. Had you been there too, you would have been won over [by their testimony].

When I heard that information, I personally talked several times to Mr. Hams, and later recounted this story in a presentation [to government officials?] in Washington, D.C., where we began an effort to determine the existence of these records. Several years went by, with naught save denials. Finally, an old friend of mine in San Francisco, Caspar Weinberger [then Sec. Of Defense] said, “Well, we are going to find out.” [Some time later] I received a call from the head of the Navy’s Freedom of Information Office in Washington. She said, “We have good news and we have bad news. The good news is that we have located the records [at Crane], but the bad news is it is part of 14,000 reels of information stored there. We are sending some people to Crane to find out if [what you want] can be released.” [Months later] there was a letter from Mr. Weinberger, dated April 20, 1967, which I quote:

Dear Fred:

In regard to the US Navy review of records in Crane, Indiana which you hope will reveal information about Amelia Earhart. I understand your eagerness to learn the outcome of the Navy’s review. Unfortunately, however, we are dealing with a very time-consuming and tedious task. There are some 14,000 reels of microfilm containing Navy and Marine Corps cryptological records, which under National Security Regulations must be examined page by page. They cannot be released in bulk. To date, over 6,000 reels have been examined in this manner and the sheer mass prevents us from predicting exactly how long it will take to examine the remaining reels. It may be helpful for you to know that the Naval Group Command’s examination of the index [has] thus far revealed no mention of Amelia Earhart. Should the information be discovered in the remaining reels however, it will be reviewed for release through established procedures and made available to you promptly and as appropriate. I wish I could be more helpful, but I hope these comments will provide assurance that our Navy people are not capriciously dragging out the review. Completion of the task will be a relief to everyone involved.

Sincerely,

‘Cap

What do I believe after 27 years of investigating? I have no belief. There is a strong possibility that she was taken by the Japanese at a very precipitous time in Pacific history. There is a possibility that, having broken the Japanese codes, Franklin Roosevelt knew she was in Japanese custody. Several times before the war the records that are now available indicate that he asked the Office of Naval Intelligence to infiltrate agents into the Marshall Islands to determine whether Earhart was alive or dead. He also asked his friend Vincent Astor in 1938, to take his private yacht to those islands to seek out possible information, but the yacht was quickly chased away by the Japanese.

Fred Goerner’s “old friend,” Caspar Willard “Cap” Weinberger, secretary of defense under President Ronald Reagan from 1981 to 1987, was another highly placed government official who helped erect and maintain the stone wall of silence around the top-secret Earhart files and led Goerner on a fruitless goose chase. Weinberger told him that The Naval Security Group Detachment at Crane, Ind., held “some 14,000 reels of microfilm containing Navy and Marine Corps cryptological records, which, under National Security Regulations must be examined page-by-page,” strongly suggesting that the Earhart secrets might someday be found there. They never were.

We do know of Roosevelt’s association with Amelia. I do not believe it is a denigration of Earhart that she was serving her government. I believe, instead of being categorized as a publicity seeker trying to fly around the world, that if she was serving her government in those capacities which are established, that she ought to be celebrated even further.

I have no hostility toward Japan. In fact, one of the writers from that country, Fokiko Iuki [sic, correct is Fukiko Aoki, see my July 16, 2017 post on Susan Butler], who has done a book on [the Earhart disappearance] from the Japanese point of view, came to America and I assisted her in its preparation. But until I have satisfied my mind where these last records [in Crane] are concerned, in particular the information from the CIC and the Navy Cryptological Security Units, I’m not going to let it stop there. (End of Goerner’s radio broadcast.)

Knowledgeable Earhart observers will note that nowhere in this 1987 broadcast did Goerner mention where he believed the fliers landed, much less the fact that he later changed his mind about such a significant piece of the Earhart puzzle.

This topic is far too complex to cover here, but in the early years of his Saipan and Marshalls investigations, as well as in his 1966 book, Goerner was adamant that Earhart and Noonan landed at Mili Atoll, based on the significant amount of evidence supporting this all but certain scenario. For much more, see Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last, Chapter VII, “The Marshall Islands Witnesses,” pages 129-134 and Chapter VIII, “Goerner’s Reversal and Devine’s Dissent,” 172-178.

Joe Klaas’s ’99 AES email traces fliers’ movements

Joe Klaas, who died in February 2016 at his home in Monterey, Calif., at 95, was probably the most gifted writer of all Earhart researchers. Unfortunately, Klaas was best known as the author of the most controversial — and damaging to legitimate research — Earhart book of all time, Amelia Earhart Lives: A trip through intrigue to find America’s first lady of mystery (McGraw-Hill, 1970).

Klaas accomplished far more in his remarkable life than pen history’s most scandalous Earhart disappearance work. Besides Amelia Earhart Lives, Klaas wrote nine books including Maybe I’m Dead, a World War II novel; The 12 Steps to Happiness; and (anonymously) Staying Clean.

In July 1999, long after the delusional Amelia Earhart Lives had done its insidious damage, Klaas wrote a fairly lengthy, pointed email to several associates at the Broomfield, Colo.-based Amelia Earhart Society including Bill Prymak and Rollin Reineck, presenting his vision of the movements of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan just after their July 2 landing in the Marshall Islands, though Klaas did not specify Mili Atoll or Barre Island as the location of the Electra’s descent.

Joe Klaas, circa 2004, author of Amelia Earhart Lives, survived a death march across Germany in 1945 and wrote nine books including Maybe I’m Dead, in 1945 and passed away in February 2016.

Klaas’s email, with the subject “Keep it Simple (I HAD TO CLEAN THIS UP, OR WE’D ALL BE LOST!),” appeared in the October 1999 edition of the Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters. Boldface emphasis mine throughout.

1937 Jaluit and Majuro residents said they heard a white woman pilot named “Meel-ya” and her companion, both prisoners, were thought to have been taken by Japanese ship to Saipan.

Others said they took her first to Kwajalein, and then to Saipan.

Medical corpsman Bilimon Amaron told Joe Gervais and Bill Prymak:

“I overheard Japanese nearby say the ship was going to leave Jaluit to go to Kwajalein . . . from there it would maybe go to Saipan.”

So the Japanese ship, Koshu, and Earhart and Noonan, were reported to have headed for Kwajalein. Naturally, all concerned assumed they were aboard the ship. But no one saw them leave on it. They assumed it.

Majuro Attorney John Heine, who saw the flyers in custody at Jaluit, said: “After the ship left Jaluit, it went to Kwajalein, then on to Truk and Saipan.” He thought the ship would later go to Japan. An event at his school fixed the date in his memory as “the middle of July, 1937.”

[Editor’s note: John Heine did not see the fliers at Jaluit or anywhere else. See page 156 and rest of “Chapter VII: The Marshall Islands Witnesses” of Truth at Last, 2nd Edition for more on Heine’s account.]

Marshall Islanders Tomaki Mayazo and Lotan Jack told Fred Goerner in 1960 that the woman flyer and her companion “were taken to Kwajalein on their way to Saipan.”

They didn’t say how they were transported.

Goerner said that in 1946 four Likiep Island residents at Kwajalein, Edard and Bonjo Capelli, and two more known as Jajock and Biki, told U.S. Navy Chief Petty Officer J.F. Kelleher that in 1937 a man and woman who crashed a plane in the Marshalls “were brought to Kwajalein.”

Bill Prymak and Joe Gervais pause with the iconic Earhart eyewitness Bilimon Amaron at Amaron’s Majuro home in 1991.

A 1946 U.S. employee on Kwajalein, Ted Burris, told Amelia Earhart Society members that his interpreter, Oniisimum Cappelle (Capelli?) introduced him to an old man who had met two Americans there “five years before the war,” which didn’t start in the Marshalls until 1942, five years after 1937.

“How did you meet Americans before the war?” Burris asked.

“Well I didn’t exactly meet them,” the old man said. “But I did bring them in.”

“Bring them in? I don’t understand.”

“A plane landed on the water,” the old man remembered. “Come. I show you.”

They walked to the south end of the perimeter road where there were two A-frame houses and a row of coconut trees.

“You see these trees? The plane was exactly in line with them.”

“How far out?”

“About a hundred yards from the land.”

“What happened then?”

“Two people got out. A man and a woman. The Captain made me take my boat out and pick them up. I didn’t talk to them.”

Lotan Jack, circa 1983, who worked as a mess steward for the Japanese in 1937, told researcher T.C. “Buddy” Brennan in 1983 that he was told by a “Japanese Naval Officer” that Amelia Earhart was “shot down between Jaluit and Mili” and that she was “spying at that time — for the American people.”

“The Captain?”

“The boss. The Japanese officer. The Captain took them away. I never saw them again. He said they were spies.” [See my Aug. 28, 2015 post, “Burris’ account among many to put Earhart on Kwaj.“]

This incident has too long been thought to be a false report that Earhart’s Lockheed 10E crashed off Kwajalein. But what the old man precisely said was:

“A plane landed on the water.”

He didn’t say it crashed there or ditched there. Planes with landing gear don’t land “on the water.”

In 1936, a concrete airstrip was built at Kwajalein. It was being used in 1937 while a still unusable seaplane ramp was under construction at Saipan.

What “landed” Earhart and Noonan “on the water” off Kwajalein was obviously a seaplane from Jaluit. Earhart’s Electra couldn’t have “landed on the water.”

Nobody ever said there was a crash at Kwajalein.

They were already in custody. How could the Japanese Captain tell the old man “they were spies” if they hadn’t arrived at Kwajalein from Jaluit lready charged with being spies?

The Kawanishi H6K was an Imperial Japanese Navy flying boat produced by the Kawanishi Aircraft Company and used during World War II for maritime patrol duties. The Allied reporting name for the type was Mavis; the Navy designation was “Type 97 Large Flying Boat”

Earhart and Noonan were then flown by land plane from Kwajalein to Saipan, where its pilot got into trouble, the very first witness in the Earhart mystery, watched “a silver two-engined plane betty-land” in shallow water along a beach. She “saw the American woman who looked like a man, and the tail man with her, led away by the Japanese soldiers.”

We must never assume every twin-engined aircraft in the Pacific had to be the Earhart Plane to be significant. We don’t need Darwin to find the missing link from Howland to Milli to Kwajalein to Saipan.

Keep it simple and follow facts in sequence to the truth. Above all, let’s start believing our witnesses.

Why would they lie?

— Joe Klaas, 7/14/99

Paul Rafford Jr. provided more witness evidence supporting the idea that Earhart and Noonan departed Kwajalein bound for Saipan in a land-based Japanese aircraft. In an unpublished 2008 commentary, Rafford recalled the account of fellow engineer James Raymond Knighton, who worked for Pan Am with Rafford at Cape Canaveral, Florida, in the 1980s and was later assigned to the U.S. Army Kwajalein Atoll facility from 1999 to 2001. Knighton worked on Roi-Namur, 50 miles north of Kwajalein, commuting to work each day by air.

“One day during lunch I was walking around Roi and I happened across an old Marshallese who was very friendly,” Knighton told Rafford in 2007.

He was back visiting Roi after a long time. He was very talky and spoke pretty good English. He was excited because he was born on Roi-Namur and lived there during the Japanese occupation and the capture by the Marines in 1944. Of course I was interested in his story of how it was living under the Japanese and the invasion. I was very inquisitive and he was happy to talk about old times. Then he said he saw Amelia Earhart on Roi when he was a young boy. It was the first white woman he had ever seen and he could not get over her blond hair. Basically, he told me that Earhart crashed on the Marshall Island of Mili. The Japanese had gotten her and brought her to Roi, the only place that transport planes could land.

For more on Rafford’s account, please see my Sept. 6, 2022 post, “Conclusion of Rafford on radio in AE Mystery.”

For much more on Joe Klaas, please click here.

![Fishing boat story 5 This story appeared at the top of page 1 in the July 13, 1937 edition of the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania)-Globe Times. “Vague and unconfirmed rumors that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan have been rescued by a Japanese fishing boat without a radio,” the report began, “and therefore unable to make any report, found no verification here today, but plunged Tokio [sic] into a fever of excitement.” The story was quickly squelched in Japan, and no follow-up was done. (Courtesy Woody Peard.)](https://earharttruth.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/fishing-boat-story-5.png?w=616&resize=616%2C352#038;h=352)

Recent Comments