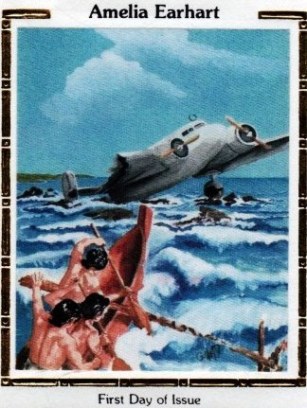

Anyone familiar with the Earhart saga knows that in 1987 the Republic of the Marshall Islands issued a set of four commemorative stamps and envelope covers in honor of the 50th anniversary of Amelia Earhart’s crash-landing off Barre Island, in the northwest section of Mili Atoll, on July 2, 1937.

The story depicted in the stamps is based largely on the narrative in Vincent V. Loomis’ 1983 book, Amelia Earhart: The Final Story, though not all of it can be considered accurate. For example, no evidence exists to support the idea presented by the authors of the one-page information sheet issued with the stamps that the fliers were taken from Jaluit to Truk, and then to Saipan. On the contrary, we have plenty of witness testimony that Earhart and Noonan were taken from Jaluit to Kwajalein, and then to Saipan.

Likewise, the statement that Earhart and Noonan, once realizing they were lost, “implemented their contingency plan and turned into a WNW course for the Gilberts,” and eventually found themselves at Mili Atoll, is speculation. Though this could have happened, we simply do not know precisely how Earhart and Noonan reached and landed off Barre Island, only that they did indeed do so.

Shortly after publication of Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last, in the summer of 2012, Frank Benjamin, an Earhart researcher and educator who was teaching at Anne Arundal Community College, in Arnold, Md., sent me the syllabus for his course, “Mysteries of History and Science.”

The Earhart disappearance was the featured event in “Mysteries of History and Science,” and Truth at Last was the only book named in the syllabus. To my knowledge, this was the first and only time this book has been the textbook for a college course, thanks to Benjamin. College historians, like virtually all historians, are notoriously and unanimously opposed to the truth in the Earhart disappearance. So much for truth in academia.

Among the materials Frank sent me was the original information sheet that described the creation of the 1987 Marshall Islands stamps and covers, issued by the Marshall Islands Philatelic Bureau. Below, for both the discerning collector and the slightly interested, is the header of the sheet’s contents, followed by its accompanying narrative.

The disappearance of American aviatrix Amelia Earhart during her around-the-world flight attempt in 1937 has been one of aviation’s great unsolved mysteries. Recent investigations by Vincent Looms and David Kabua (son of Marshalls President Amata Kabua) have led to eyewitness accounts of what happened to Earhart and her navigator Frederick Noonan. This issue is based on those accounts.

The Amelia Earhart commemorative is the Marshall Islands CAPEX ’87 issue, released concurrently at Majuro, capital of the Marshalls, and Toronto, Canada. Earhart tended wounded soldiers in a Toronto hospital during World War I, and her first brush with the excitement of aviation came at the Toronto Aero Club Fete of 1918.

Her associations with Canada continued: her 1928 flight, in which she was the first woman to fly the Atlantic, went from Boston, MA, Halifax, NS, and Trepassey, NWF to Carmarthen Bay, Wales; her flight of 1932, when she became the first woman to solo the Atlantic, was routed from Teterboro, NJ to St. John, NB, to harbor Grace, NWF and on to Culmore, Ireland.

This set of four postage stamps issued by the Republic of the Marshall Islands in 1987 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Amelia Earhart’s last flight. The stamps (clockwise from top left) are titled: “Takeoff, Lae, New Guinea, July 2, 1937; USCG Itasca at Howland Island Awaiting Earhart; Crash Landing at Mili Atoll, July 2, 1937; and Recovery of Electra by the Koshu.” Frank Benjamin enlarged and mounted these stamps, and they are an impressive part of his unique Earhart display.

At 10 a.m. on July 2, 1937, Earhart’s Electra took off from the Cliffside runway at Lae, New Guinea bound for Howland Island, via the Nikumanus and Nauru; if she reached it all right, the remaining legs to Hawaii and California would be easy. A Guinea Airways pilot [probably Jim Collopy], who saw her takeoff, commented that the craft was so overloaded that it dropped off the end of the runway and wet its props in the Gulf of Huon before Earhart could get to flying speed.

Awaiting her on Howland Island, 2500 [actually 2,556] miles away, was the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Itasca, equipped with the latest navigation and communication devices. Commander Warner K. Thompson had search lights aimed skyward all night as a beacon; with the dawn, the Itasca began burning bunker oil, which put out a black plume visible for thirty miles around. An experimental Navy direction-finding unit (DF) was set on Howland itself, and officers also scanned the skies with binoculars.

One of four covers issued in June 1987 to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Amelia Earhart’s landing off Barre Island, Mili Atoll, in the Marshall Islands.

All through the night and the next morning, radio operators struggled to establish two-way communications with the Electra. Earhart’s transmissions would drift in and out, but she seemed unable to understand messages the Coast Guardsmen were sending, and she never stayed on the air long enough for them to fix her position. Each succeeding broadcast seemed more desperate and confused, until, two hours after sunrise locally, her last message: “We are on the line of position 157-337. We are running north and south.” Then, fifty years of silence.

Thinking they were south of Howland Island, but unable to find it, Earhart and Noonan implemented their contingency plan and turned into a WNW course for the Gilberts. However, since they were north of Howland, their new course carried them directly over Mili Atoll, most southeasterly of the Japanese-held Marshall Islands.

Two Mili fishermen on Barre Island, Lijon and Jororo Alibar, saw a silver plane approach and crash-land on the nearby reef, breaking off part of its right wing. The two Marshallese hid in the underbrush and watched as two white people exited the wreck and came ashore in a yellow raft. A little while later Japanese soldiers arrived to take hold of the fliers. When the shorter flier screamed, the Marshallese realized one was a woman. They remained hidden until long after the captives were taken away.

Another of the four covers issued in June 1987. this one depicting a native Marshallese, probably Lijon, a Japanese officer and the Japanese survey ship Koshu, which some believe loaded the damaged Electra on its stern and eventually took it to Saipan.

The Japanese Navy Survey Ship Koshu was sent from Ponape to Barre Island to pick up Earhart’s Lockheed Electra. The canvas sling the Koshu normally used for plucking Japanese seaplanes from the water was still around the big silver bird when the ship returned to Jaluit on July 19, where Japanese Medical Corpsman Bilimon Amaran [sic], who treated Noonan’s crash injuries, boarded the ship and saw Earhart.

The Koshu then sailed immediately for Truk, where Earhart and Noonan were taken aboard a flying boat to Saipan, the Japanese military headquarters in the Pacific. Saipanese Josephine Blanco witnesses the Japanese plane land in Tanapag Harbor, and she was taken by her brother-in-law, a Japanese working at the base, to see the Americans.

Earhart and Noonan were considered spies by the Japanese and so were held on Saipan for questioning. Their fate remains unknown.

This stamp [sic] is based in Amelia Earhart: The Final Story, by Vincent Loomis.

It was designed by William R. Hansen, Lunar Artist-Apollo 16, who also designed the CPAEX cancel and cachet and wrote this panel. The House of Questa printed the issue to the standard commemorative specifications.

I should not have to mention that Loomis was not alone in his findings that revealed the presence of the lost fliers at Mili Atoll in early July 1937. The investigations of other authors and researchers, including Fred Goerner, Oliver Knaggs, Bill Prymak and most recently Dick Spink and Les Kinney have strongly corroborated the truth depicted in the 1987 commemorative stamps issued by the Republic of the Marshall Islands. But what has always been accepted as fact by the Marshallese people continues to be denied by the U.S. government and falsely labeled a “mystery,” while virtually nobody ever questions or challenges one of the greatest lies in American history.

![Fishing boat story 5 This story appeared at the top of page 1 in the July 13, 1937 edition of the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania)-Globe Times. “Vague and unconfirmed rumors that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan have been rescued by a Japanese fishing boat without a radio,” the report began, “and therefore unable to make any report, found no verification here today, but plunged Tokio [sic] into a fever of excitement.” The story was quickly squelched in Japan, and no follow-up was done. (Courtesy Woody Peard.)](https://earharttruth.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/fishing-boat-story-5.png?w=616&resize=616%2C352#038;h=352)

What a great bit of support that your book is used as a textbook in a history course! My favorite part of this story about the Marshall Islands stamps is the specific image of the “yellow raft that got larger” in one of the stamps. Thanks for the extra info, Mike!

LikeLike

These exquisite and most colorful stamps created by *William R. Hansen, paint us a picture and give us visual portrait of Amelia Earhart’s landing in the Marshall islands.

What better way to understand this historical event and learn of Amelia’s fate at the hands of the Japanese.

Now why doesn’t the U.S. Postal Service issues these commemorative stamps?

Something VERY FISHY is going on here, wouldn’t you say?

I’m sure the POSTMASTER will issue a Ric Gillespie [the search continues stamp] and everyone will want those????

LikeLike

When I worked on Kwajalien in the early 70’s, a Marshallese friend of mine told me that he remembered the Japanese brought Earhart and Noonan to Kwajalien. After all these years of reading all the other assumed accounts, I have always remembered what my friend told me.

LikeLike

Was your Marshallese friend named John Tobeke or Mera Phillip? We have accounts from both of these eyewitnesses that were reported initially in the Kwajalein Hourglass by local writers Jane Toma and Eugene Sims. Do you recall the person’s name, or any other details? Please try to remember, as these kinds of accounts are valuable additions to the Earhart saga.

Thanks.

MC

LikeLike

No, I am sorry, I can’t remember. But I do remember that he worked for the King.

LikeLike

rfboyd –

This friend of yours worked for the KING? What type of work did he do for the KING?

LikeLike

On a different note, why hasn’t someone looked further into or asked more questions about Matilda’s sister – *Consolacion? She was the young girl who gave Amelia the fresh fruit and in return Amelia gave her a ring. Later, when her sister was sick, “she took the ring off her finger and gave me that ring and I took care of that ring until after the war.” Matilda said, at that point, her niece, Trinidad, “borrowed the ring when they went to Truk and it was lost there,”

What did the ring look like?

We know that Amelia was being referred to or called (Ameba) by the villagers who were helping her at this time.

One mentions that her hair had grown longer.

LikeLike

When I lived on Roi-Namur (Kwajalein Atoll) from 1998 to 2003, I knew a fellow worker named Ted Burris, He wrote a book titled “Kwajalein: From Stonehenge to Star Wars.” Since I also wrote for the Hourglass, Ted asked me to look at his manuscript for any grammatical errors. In it was a short story about a Marshallese who lived on Ebeye, the island next to Kwajalein where the Marshallese lived. The old man told him about a plane that landed in the water. The Japanese made him take them in his boat to pick up the plane’s passengers, which were a Caucasian man and woman. The Japanese told the Marshallese not to talk to the passengers. They were later transferred to Roi, where the main airport was located, and flown to Saipan. I used to work at that airport on Roi and often walked past the old Japanese headquarters next to the runway. My time on Roi was one of the most fascinating experiences in my life. Ted’s book can be found on Amazon.

LikeLike

[…] they saw the Japanese tow away a plane. In 1987, the Republic of the Marshall Islands even issued a series of postage stamps depicting their stories of Earhart’s landing and […]

LikeLike