“Amelia Didn’t Know Radio” — Almon Gray

Once again I’m privileged to offer yet another erudite presentation on radio and Amelia Earhart by the late Almon A. Gray, this one titled “Amelia Didn’t Know Radio.” This article initially appeared in the November 1993 edition of U.S. Naval Institute History magazine before Bill Prymak presented it in the December 1993 issue of his Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters.

After graduating from the George Stevens Academy in 1928 and the Massachusetts Radio Telegraph School in 1930, Gray enlisted in the Navy, where he was a radioman and gunner aboard cruiser-based aircraft, and he also learned to fly.

Following his Navy enlistment he joined Pan American Airways, and in 1935 helped build the bases to support the first trans-Pacific air service, and was first officer-in-charge of the PAA radio station on Wake Island. After the San Francisco-Hong Kong air route was opened in late 1935, he was a radio officer in the China Clipper and her sister flying boats. Later he was assistant superintendent of communications for PAA’s Pacific Division. Gray, who flew with Fred Noonan, was a Navy Reserve captain and a major figure in the development of the Marshall Islands landing scenario. He died at 84 on Sept. 26, 1994 at Blue Hill, Maine

This is the first of a three-part presentation. Boldface emphasis mine throughout.

“Amelia Didn’t Know Radio”

by Captain Almon A. Gray, U.S. Naval Reserve (Ret.)

Almost certainly, Amelia Earhart could not get a bearing on the radio beacon on the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Itasca (WPG-321), lying off the beach at Howland Island, rose the frequency that she had designated –7.50 Mcs* — was so high that her direction finder (DF) was inherently incapable of taking bearings on it.

(* Since 1937 the unit of measurement for radio frequencies has been changed from “cycles” to Hertz (Hz), consequently Megacycles (MCs) and MegaHertz (MHz) will be used interchangeably , as will Kilocycles and Kilohertz (kHz).)

That Earhart and Fred Noonan failed to reach Howland Island on their 1937 around-the-world flight because of radio problems has been studied before — but little has been written about the specifics.

Capt. Almon Gray, USNR (Ret.) wrote extensively on Amelia Earhart’s radio problems during her last flight. Gray, a Navy Reserve captain and Pan American Airways China Clipper flight officer, flew with Fred Noonan in the 1930s and was an important figure in the development of the Marshall Islands landing scenario.

A failure in the plane’s antenna system, which made it impossible to receive signals on the fixed antenna, also was a factor. Had she or Noonan known enough about the system to work around the failure, they could have established voice communications with the Itasca, where someone surely would have suggested they try taking bearings on the vessel’s 500-kilocycle beacon. It could have made all the difference.

BACKGROUND: In early 1937, several weeks before departing Oakland, California, for Honolulu — the first leg of an intended west-about flight around the world — Earhart met at Alameda, California with George Angus, the Superintendent of Communications for the Pacific Division of Pan American Airways (PAA). Angus directed the radio communication and DF [direction finding] networks that supported the PAA clippers on their Pacific crossings, and she was looking for help to augment Noonan’s celestial navigation.

The airline then had specially designed versions of the Adcock radio DF system in service at Alameda, Mokapu Point on Oahu in the Territory of Hawaii, Midway Island, Wake Island, Guam, and Manila in the Philippines. They could take bearings on frequencies much higher than could conventional loop-type direction finders — like Earhart’s — and were effective over much greater distances. These high frequency DFs were the only ones of their type in the United States and its territories. Angus agreed to help and went to work on the details.

This was complicated inasmuch as PAA could receive but not transmit on either of Earhart’s communications frequencies — 3105 or 6210 kHz — and could not transmit voice on any frequency. Earhart and Angus decided that the aircraft would request a bearing by voice on the frequency in use — usually 3105 kHz at night and 6210 kHz during the day — and follow the request with a series of long dashes lasting in the aggregate a couple of minutes.

The PAA DF station would rake a bearing on the transmission and transmit it to the plane on another previously agreed upon PAA frequency, using continuous wave (CW) telegraphy sent at such a slow speed that the individual dots and dashes could be copied on paper and later translated into numbers.

This arrangement was tested on the flight from Oakland to Honolulu; PAA took the bearings on 3105 KHz and transmitted the bearings in Morse code on 2986 KHz. The flight was handled much the same as a routine Clipper flight. Captain Harry Manning, former captain of the SS Roosevelt,the ship that brought her home from Europe after her 1928 trans-Atlantic flight — and a long-time friend, was an experienced radio operator and handled the Electra’s radio and DF gear while regular PAA professional radio operators manned the ground stations. Radio bearings furnished the plane at frequent intervals, first from Alameda and later from Mokapu Point, checked well with the positions Noonan determined by celestial navigation. Nearing Oahu, Manning set up the plane’s DF to home on the 290 kHz marine radio beacon at Makapu Point, near Diamond Head, and Earhart homed in on it to a successful landfall.

While attempting takeoff for Howland-Island from Luke Field, near Honolulu, on March 20, 1937, Earhart ground-looped the Electra, damaging it to the extent that it was shipped back to the Lockheed plant in California for repairs. The radio gear sustained no major damage, but the Western Electric Model 20B radio receiver and its remote-control apparatus were replaced by a Bendix aircraft radio receiver and accessories. The stub mast supporting the V-shaped fixed antenna also was moved a bit forward, and the antenna feed line was rerouted. The late Joseph Gurr, then a moonlighting United Airlines technician, did the work.

Amelia Earhart’s seriously damaged Electra 10E after her Luke Field, Hawaii “ground loop” on March 20, 1937. Amelia and Fred Noonan can be seen standing next to the pilot’s side of plane. The Electra was sent back to the Lockheed plant in Burbank for months of costly repairs. The radio gear sustained no major damage, but the Western Electric Model 20B radio receiver and its remote-control apparatus were replaced by a Bendix aircraft radio receiver and accessories.

THE NEW RECEIVER: The receiver installed at Lockheed was an experimental model incorporating the latest improvements. Only three experimental units were built, although Bendix later marketed an almost identical design as the Type RA-1 Aircraft Radio Receiver.

The experimental model was a continuous turning superheterodyne that covered the spectrum from 150 to 10,000 kcs in five bands. It could receive voice, CW, or modulated CW (MCW) signals and could be controlled remotely from the cockpit. A switch permitted the operator to connect the receiver to either the conventional wire antenna or the loop antenna. When the loop was used, the combination became an effective radio DF system capable of accurate bearings on frequencies between 150 and approximately 1800 kcs. Signals on frequencies higher than 1800 kcs could be heard, but very seldom could accurate bearings be obtained. Earhart was apparently unaware of this. The receiver was powered by a dynamotor operated by storage batteries charged by the main engines.

THE RADIO SYSTEM: When the plane left the Lockheed plant, the radio system consisted of the following elements:

– The experimental Bendix aircraft radio receiver.

– Western Electric Model 13-C 50-watt aircraft transmitter with three crystal-controlled channels: 500, 3105, and 6210 kHz — capable of voice or CW transmissions. It was mounted in the cabin, but there were remote controls in the cockpit.

– A prototype of a Bendix Type MN-20 rotatable shielded loop antenna. It was mounted on the fuselage above the cockpit; the knob that rotated it was on the cockpit overhead between the pilots. It was used primarily for taking radio bearings but was useful as a receiving antenna in static caused by heavy precipitation.

– Fittings at each side of the cockpit for connecting a microphone, headphones, and telegraph key.

– A telegraph key and a jack for connecting headphones at the navigator’s table.

– A 250-foot flexible-wire trailing antenna on an electrically operated, remote-controlled reel at the rear of the plane. The wire exited the lower fuselage through an insulated bushing and had a lead weight, or “fish,” at the end to keep it from whipping when deployed. A variable loading coil used in conjunction with this antenna permitted its use on 500 kHz., and the antenna was long enough to give excellent radiation efficiency on all three transmitting frequencies.

– A fixed, Vee-configured wire antenna with its apex at a stub mast mounted on the top of the fuselage, over the center section of the wing, and its two legs extending back to the two vertical tail fins. The antenna was so short that its radiation efficiency was extremely low; it was adequate for local communications around an airport when it was not feasible to have the trailing antenna deployed, but not for the long-distance communication Earhart required for her transoceanic flight.

The Bendix RA-1B, used in Amelia Earhart’s Electra during her final flight without apparent success, was a brand new product and was reputed to be pushing the state of the art in aircraft receiver design.

Either wire antenna could be selected from the cockpit. The one selected both transmitted and received by means of a send-receive relay that switched the antenna from the receiver to the transmitter when the microphone button was depressed, and switched it back to the receiver when the button was released.

MISTAKES AT MIAMI: After deciding to change her route to east-about, in late May 1937 Earhart flew the plane to Miami, where she had the trailing antenna and associated gear removed completely. John Ray, an Eastern Airlines technician who had his own radio shop as a sideline, did the work. Once again, Amelia obviously did not comprehend the devastating impact this would have on her ability to communicate and to use radio navigation. With only the very short fixed antenna remaining, virtually no energy could be radiated on 500 KHz. This not only foreclosed any possibility of contacting ships and marine shore stations but precluded ships — most important, the Itasca — and marine shore-based DF stations from taking radio bearings on the plane, inasmuch as 500 kHz was the only one of her frequencies that fell within the range of the marine direction finders. Any radio aid in locating Howland Island would have to be in the form of radio bearings taken by the plane on radio signals from the Itasca. Earhart had cut her options severely.

The shortness of the remaining antenna also drastically reduced the power radiated on the two high frequencies. Paul Rafford Jr., a NASA expert in this field involved in forecasting long-range communication requirements to support astronaut recoveries, estimated that the radiated power on 3105 KHz. was about one-half watt. This obviously was a tremendous handicap in the high static level of the tropics.

The fixed antenna also may have been at least partly responsible for the distortion in Earhart’s transmitted signals reported by the operators at Lae, New Guinea, and Howland as affecting the intelligibility of her voice transmissions. A mismatch between the antenna and the final amplifier of a WE-13C transmitter could cause the transmitter to over-modulate and thus introduce distortion.

After a few days in the Pan American Airways shops during which all systems, including the antennas, were tuned and peaked, the plane departed Miami on June 1, 1937 to resume the flight around the world.

Despite these shortcomings, Earhart got as far as the Dutch East Indies without major incident. There, however, because of her unfamiliarity with radio matters, she unwittingly made the mistake that ultimately led to her failure to reach Howland Island.

THE FAULTY PLAN: The legs from New Guinea to Howland Island and from Howland to Hawaii were the most difficult navigational portions of the flight, and three small vessels were stationed along the way to assist. Each planned to use the ship’s transmitter as a radio beacon for Earhart and Noonan to supplement Noonan’s celestial navigation.

– The USS Ontario (AT-13) was on station midway between Lae and Howland.

– The USS Swan (AVP-34) was positioned midway between Howland and Hawaii.

– The USCGC Itasca was at Howland. Her beacon was particularly important; should Noonan’s celestial navigation not put them within visual range of the small, low-lying island, homing in on the Itasca’s signal would be their only chance.

By June 23 these vessels were on or approaching their respective stations but had not been issued their radio beacon frequency or procedures. That day, in a message addressed to Earhart at Darwin or Bandoeng. Richard Black — Earhart’s representative on board the Itasca — advised her of the radio frequencies available on the three ships and asked her to designate the frequency she wished each ship to use when transmitting beacon signals. This message caught up with Earhart at Bandoeng, Java.

(End of Part I.)

Rafford’s questions about Earhart comms conclusion

We continue with the conclusion of Paul Rafford Jr.’s “Amelia Earhart – Some Unanswered Questions About Her Radio Communication and Direction Finding” This analysis appeared in the September 1993 issue of the AES Newsletters. Boldface emphasis mine throughout; underline emphasis in original AES Newsletters version.

“Amelia Earhart – Some Unanswered Questions About Her Radio Communication and Direction Finding” (Part II of two.)

by Paul Rafford Jr.

June 22, 1993

Why was the Howland direction finder never able to get bearings on Earhart?

The reasons here are several fold. Primarily, it was because Earhart never stayed on the air long enough for an operator to take a bearing. But, even if she had stayed on longer, the combination of her low transmitting power with the inadequacy of the jerry-rigged aircraft DF on Howland, would have limited its range to less than 50 miles. In other words, on a clear day she could have seen the island before the island could have taken a bearing on her.

The questions that arise out of this fiasco are:

1) Why did whoever organized the project of setting up the direction finder on Howland not know of its extreme limitation?

2) Why did Earhart, supposedly a consultant to the government on airborne direction finders, never stay on the air more than seven or eight seconds?

Why did Earhart ask for 7500 kHz [kilohertz] in order to take bearings on the Itasca, considering it could not be used with her direction finder?

The Coast Guard Cutter Itasca was anchored off Howland Island on July 2, 1937 to help Amelia Earhart find the island and land safely at the airstrip that had been prepared there for her Lockheed Electra 10E.

Supposedly, “7500” came about through Earhart’s ignorance of the two different designations for radio channels. It has been theorized that she confused 750.0 meters with 7500 kHz. Of course, 750.0 meters is 400 kHz, a bona fide beacon frequency, while 7500 kHz is 40 meters.

It would appear that not only did she get meters and kilocycles mixed up but she overlooked the decimal point.

Bob Lieson, a former co-worker of mine had done a stint on Howland Island as radio operator shortly after Earhart’s disappearance. I asked him if the Itasca might have used 7500 kHz for any other purpose than to send dashes for Earhart. “Oh yes,” he replied, “We used 40 meters for contact with the Coast Guard cutters when they were standing off shore.”

This brings up two questions:

1) Could it have been that Earhart was not confusing meters and kilocycles but knew ahead of time that 7500 kHz was the Itasca’s link with Howland so would be available on call?

2) Why would Noonan, both a navigator and radio operator, let Earhart make the potentially fatal mistake of trying to take bearings on 7500?

Coast Guard Chief Radioman Leo Bellarts led the radio team aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Itasca during the final flight of Amelia Earhart.

Why did Earhart not seize on the one occasion where she heard the Itasca and knew it was hearing her, to try and establish communication with the crew?

This is the most incredible part of the Earhart saga. At 1928 GMT she announced, “Go ahead on 7500 kilocycles.” Then, at 1933 GMT she announced, “We received your signal but unable to get a minimum.” Supposedly, she is hopelessly lost and about to run out of gas. Now, after searching for Howland for over an hour, for the first time she is hearing the Itasca and knows the ship is hearing her. Does she breathe a giant sigh of relief because she has finally made contact with the crew? Of course they are using code but Noonan is a radio operator and can copy code while replying to the ship by voice on 3105 kHz.

No! Instead of desperately trying to keep in contact, Earhart is not heard from for over forty minutes. When she returns to the air it is only to make one brief, last transmission. She declares she is flying north and south on a line of position 157-337 and will switch to 6210. The Itasca never hears her again.

The Mysterious Post-Flight Radio Transmissions

What was the source or sources of the mysterious signals heard on Earhart’s frequencies that began just hours after her disappearance and lasted for several days?

During the hours and days immediately following Earhart’s disappearance, various listeners around the Pacific heard mysterious signals on her frequencies.

Ten hours after the Itasca last heard her, the crew of the HMS Achilles intercepted an exchange of signals between a radiotelephone station and a radiotelegraph station on 3105 khz. The telephone station requested, “Give us a few dashes if you get us.” The telegraph station replied with several long dashes. The telephone station then announced, “KHAQQ, KHAQQ.” (Earhart’s call letters).

Believing they were hearing the plane safely down somewhere, the Achilles sent the U.S. Navy a message to that effect. However, in its reply, the Navy denied this possibility.

Two hours later, Nauru Island heard the highly distorted voice of a woman calling on 6210 khz. They reported that, although they could not understand the words, the voice sounded similar to Earhart’s when she had passed by the island the night before. However, this time there was “– no hum of engines in the background.”

West Coast amateur radio operators Walter McMenamy (left) and Carl Pierson, circa 1937, claimed they heard radio signals sent by Amelia Earhart, including two SOS calls followed by Earhart’s KHAQQ call letters.

Meanwhile in Los Angeles, Karl Pierson and a group of his radio engineering colleagues set up a listening watch on Earhart’s frequencies. During the early morning hours of July 3rd, they heard SOS calls on 6210 kHz both voice and telegraph. Of particular interest was the fact that the voice was a woman’s. However, neither call included enough information to identify the plane’s position or status.

The Pan Am stations at Wake, Midway and Honolulu managed to pick up a number of weak, unstable radio signals on Earhart’s frequencies and take a few bearings. But, the stations never identified themselves or transmitted any useful information.

Despite his failure to get bearings earlier, the Howland operator got a bearing on a fairly strong station shortly after midnight on July 5th. It indicated the transmitter was either north northwest or south southeast of Howland. But, again there was no identification or useful information from the station.

The question that arises here is, were the distress calls heard by Karl Pierson and his group authentic? If they were, why did the calls not include more information? If they were not, who would have sent them and why?

, “Earhart’s “post-loss messages”: Real or fantasy?” and “Experts weigh in on Earhart’s “post-loss” messages.”

Calvin Pitts rips Dimity’s Earhart flight analysis

With the recent publication of E.H. “Elmer” Dimity’s 1939 analysis of Amelia Earhart’s last flight, I’ve been gently reminded that, as an editor, I could have done a far better job of reviewing Dimity’s article. I’ve never been particularly drawn to the Itasca flight logs and have never claimed any expertise about them, as for me, they provide more confusion than clarity. But I can still proofread and compare times and statements attributed to them.

This I failed to do, in large part because I assumed that Bill Prymak, the editor of the Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters, had done this already, before presenting Dimity’s work, or that Prymak would have made some kind of a disclaimer to accompany it. He did neither, and my own disclaimer following Part II, in light of Calvin Pitts’ stunning findings, should have been far more emphatic. I broke a journalism rule — never assume anything — that I’ve always done my best to obey, until now.

Regular readers of this blog are familiar with Calvin, best known for his 1981 world flight, when he and two co-pilots commemorated the 50th Anniversary of the Wiley Post-Harold Gatty World Flight in 1931. The 1981 flight was sponsored in part by the Oklahoma Air & Space Museum to honor the Oklahoma aviator Post. Calvin has already graced us with his impressive five-part analysis of Amelia Earhart’s last flight. To review this extremely erudite work, please click here for Part I, from Aug. 18, 2018.

Calvin Pitts in 1981, with The Spirit of Winnie Mae and the thermos Amelia Earhart carried with her on her solo Atlantic Crossing in 1932. The thermos was on loan from Jimmie Mattern, Wiley Post’s competitor who flew The Century of Progress Vega in an attempt to beat Wiley in the 1933 solo round-the-world race, but Mattern crashed in Siberia. Calvin brought Amelia’s thermos along with him on his own successful world flight in 1981.

Our focus today is a striking example of a difficult exercise in attention to detail, and an object lesson in the old axiom, “Never assume anything.” We appreciate Calvin taking the time to set the record straight. With his learned disputation below, in addition to his previous contributions, Calvin has established himself as the reigning expert on the Itasca-Earhart flight logs, if not her entire final flight, at least in my opinion. Without further ado, I’ll turn it over to Calvin, who has many important things to tell us:

First, I want to thank Mike Campbell for his passion and dedication to The Amelia Story. SHE — and history — have had no better friend.

I also appreciate Mike’s ability to dig up “forgotten” history. As a lover of history’s great moments, I am always fascinated by the experiences of others. Also, as one who has made a 1981 RTW flight in a single-engine plane, passing over some of AE’s ’37 flight paths from — India – Singapore – Indonesia – Australia – New Guinea – Solomon Islands, Tarawa and within a few miles of Howland — I was drawn to this story, and to this blog’s record of it.

Recently, I was fascinated by the publishing of Dimity’s 1937-1939 insights into the details of AE’s flight. However, upon reading it, I spotted some errors. Ironically, I was at that very time re-studying the Itasca Logs as I re-lived some of the details and emotions of the most famous leg of any flight. I had the Itasca details in front of me as I read.

Because it is easy to unconsciously rewrite and revise the historical record, I felt an unwelcomed desire to share some errors which were in Dimity’s interesting account. I shared my thoughts privately with Mike, and he, in turn, asked me to make them public. I’ve had a long aviation career, and have no desire to add to it. At 85, I’m retired in a log house on a small river with more nature-sights than anyone could deserve. I’ve no yearning for controversy. But Mike asked, so here are some observations. If you spot errors in my response, please make them known. Only one set of words are sacred, but these at hand do not qualify.

Calvin Pitts’ analysis of:

“Grounds for a Possible Search for Amelia Earhart” (First of two parts)

by E.H. “Elmer” Dimity, August 1939

(Editor’s note: To make it easier to understand and track the narrative, Dimity’s words will be in red, Calvin Pitts’ in black, with boldface emphasis mine throughout.)

At 3:15 [a.m.] in the morning after her takeoff Miss Earhart broadcast “cloudy weather,” and again, an hour later, she told the Itasca that it was “overcast,” and asked the cutter to signal her on the hour and half hour.

I am sitting here reading Dimity’s Part II of the “Grounds for Earhart’s Search” with a copy of the Itasca LOGS on the screen in front of me. My challenges to Dimity’s reproduction of the Itasca Earhart flight logs are based, not upon prejudice, but upon the actual records compiled and copied from those 1937 Logs.

At 3:15 a.m. Howland time, times recorded by the crew of the Itasca, there is no such record of “cloudy weather.”

Copy of an original page from Chief Radioman Leo Bellarts of the Itasca showing the entry of the now-famous 2013z / 8:43 am call, “We are on the line 157-337, will repeat message . . .”

From position 2/Page 2: At 3:15 am, Chief Radioman Leo Bellarts records: “3:15-3:18, Nothing heard from Earhart.”

Position 1/Page 1: At 3:14 am, Thomas J. O’Hare, Radioman 3rd class records: “Tuned to 3105 for Earhart,” with no additional comment. Seven minutes later at 3:21 am, he records: “Earhart not heard.”

Position 2/Page 2: However, at 3:45 a.m., not 4:15 a.m., Bellarts records: “Earhart heard on the phone: WILL LISTEN ON THE HOUR AND HALF ON 3105.”

Position 1/Page 1: At the same time, 3:45 a.m., O’Hare records: “Heard Earhart plane on 3105.” That was it. No reference to “overcast,” and no request for a signal.

However, in his book, Earhart’s Flight Into Yesterday (2003), Laurance Safford copies Bellarts’ statement, except that he adds the word “Overcast.” The word “overcast” is not in the Itasca log at that time.

Position 2/page 2: According to the log’s record, it was not until 4:53 a.m., more than 1.5 hours later, that the phrase “PARTLY CLOUDY” appears.

Earlier, at 2:45 a.m., Safford quotes a statement by author Don Dwiggins about 30 years later: “Heard Earhart plane on 3105, but unreadable through static . . . however, Bellarts caught “Cloudy and Overcast.”

Yet, Bellarts, who was guarding Position 2/Page 2 made no such statement on his report. The statement, “unreadable through static” was recorded by Bellarts at 2:45, but that was it.

Bellarts was also the one who recorded, an hour later at 3:45: “Will listen on the hour and the half on 3105.” These issues are very minor to most readers. But to those at the time, where minutes count for survival, the devil was in the details.

Also, there is the historical and professional matter of credibility. If one is not accurate, within reasonable expectations, of quoting their sources correctly, then the loss of credibility results in the loss of confidence by their readers.

More than an hour later, at 4:42 a.m., the Earhart plane indicated for the first time that it might be off course, and made its first futile plea for aid in learning its position. The plane asked, “Want beatings (sic) on 3105 KC on the hour. Will whistle into the microphone.”

At 4:42 a.m., which is a very precise time, there is nothing recorded at any station. But we can bracket an answer. Bellarts records the following at 4:30 a.m.: “Broadcast weather by Morse code.” His next entry, at 4:42 a.m., is an empty line.

At 4:53 a.m., Bellarts states, “Heard Earhart [say] ‘Partly Cloudy.‘ ”

Also, Position 1/Page 2 of this record states: “4:40 a.m. – Do you hear Earhart on 3105? . . . Yes, but can’t make her out.” Five minutes later at 4:45 a.m. (with no 4:42 notation at this position): “Tuned to Earhart, Hearing nothing.” There is no recorded statement here from her about being off-course or whistling.

Half an hour passed (5:12 a.m.), and Miss Earhart again said, “Please take a beating on us and report in half hour will make noise into the microphone. About 100 miles out.” Miss Earhart apparently thought she was 100 miles from Howland Island.

5:12 a.m.? At neither position is there a posting at 5:12. At 5:15, one says, “Earhart not heard.” And the other, at 5:13 says, “Tuned to 3105 for Earhart signals. Nothing yet.”

Radio room of USCG Cutter Tahoe, sister ship to Itasca, circa 1937. Three radio logs were maintained during the flight, at positions 1 and 2 in the Itasca radio room, and one on Howland Island, where the Navy’s high-frequency direction finder had been set up. Aboard Itasca, Chief Radioman Leo G. Bellarts supervised Gilbert E. Thompson, Thomas J. O’Hare and William L. Galten, all third-class radiomen, (meaning they were qualified and “rated” to perform their jobs). Many years later, Galten told Paul Rafford Jr., a former Pan Am Radio flight officer, “That woman never intended to land on Howland Island!”

The above “about 100 miles out” message was sent at 6:45 am, about 1.5 hours later.

The Itasca could not give her any bearing, because its direction finder could not work on her wavelength. An hour later, at 7:42 a.m., Miss Earhart said, “We must be on you but cannot see you. Gas is running low. Have been unable to reach you by radio. We are flying at 1,000 feet.”

Strangely, even amazingly, sandwiched between numerous bogus times, 7:42 am IS correct.

This was a little more than 15 hours after the takeoff.

Would you believe that, more than 19 hours after takeoff, this call was made? Here, there are four unaccounted-for hours in Dimity’s record-keeping.

The ship carried 1,150 gallons (sic) of gas, enough for about 17 hours in the air under normal conditions.*

Would you believe “more than 24 hours” of flight time, a seven-plus hour discrepancy?

* AES calculates 24-25 hours. — (Whoever AES is, this is more realistic and accurate.) Editor’s note: AES is The Amelia Earhart Society, almost certainly Bill Prymak’s estimate.

Perhaps the plane had encountered heavier weather earlier, or in just bucking the headbands had used more gas than anticipated. At any rate, Miss Earhart must have flown about 1,300 miles from the point of her first known position, when she first said her gas was running low.

An interesting question: When was her first known position? And measured by what evidence? 1,300 statute miles from the transmission at 7:42 a.m./1912 Greenwich Mean Time (GMT and z, for Zulu, are the same) would put her about halfway between Nukumanu Atoll and Nauru. If Nukumanu was her first or last known position at 5:18 p.m. Lae/0718 GMT/ 7:48 p.m. (Howland, the previous day), then that is roughly 1,600 statute miles, not 1,300.

This distance, with perfect navigation, should have taken her to Howland Island, and that without doubt is the reason she said, “We must be on you.” If the plane had hit its mark, why could she not see the island or the Itasca (Having such a flight under my belt, I could offer several reasons) with a clear sky and unlimited visibility? Even a smoke screen laid down by the cutter to help guide her evidently escaped her view. It is impossible that she was where she thought she was — near Howland.

Although Miss Earhart reported at 11:13 a.m. that she had fuel left for another half hour in the air, the contact was poor and no landfall position was heard.

At 11:13 a.m., the Navy ships and Itasca had been searching the ocean for some two hours or more. The “last known” message from Earhart was at 8:43 a.m./2013z when she said, “We are on the line 157/337.” The message “fuel for another half hour” was made at 7:40 a.m./1910z, some 3.5 hours before Dimity’s “11:13 a.m.” time.

This particular time discrepancy possibly could be corrected by adjusting it to a new time zone in Hawaii, but that would destroy the other record-keeping. At no place in this Itasca log saga were they talking in terms of U.S.A. times. The Itasca crews were recording Howland local time. If someone has proof otherwise, it should be provided, and it will alter the story.

Fifteen minutes later (11:28 a.m.) she said, “We are circling, but cannot see island. Cannot hear you,” and asked for aid in getting her bearings. This plea she repeated five minutes later (11:33 a.m.).

This “circling” reference was made at 7:58 a.m., some 3.5 hours earlier. However, something which is often missed is the fact that the word “CIRCLING” is in doubt even within the footnotes of this log itself. It is listed as “an unknown item.” It was a word they did not hear clearly. It could have been, “We are listening.” No one knows.

It will be recalled that at 11:12 a.m., Miss Earhart said she had only a half-hour’s fuel left, but an hour later, at 12:13 p.m., she called the Itasca to report, “We are in line of position 157 dash 337. Will repeat this message on 6210 KC. We are running north and south.”

This “line 157/337” radio call, NOT a “line of position” call, was made, as already stated, at “8:43 a.m./2013z” and NOT at “12:13.” Somehow Dimity has a discrepancy here of some 3.5 hours from the Itasca logs.

The “157/337 line of position” is not only NOT what she said, but it is inaccurate for any researcher who understands basic navigation. The LOP of 157/337 existed only as long as the sun’s azimuth remained 67 degrees.

As the sun rose above the horizon, its azimuth changed 1+02 hours after sunrise (6:15 a.m. Howland time on July 2, 1937.) That meant that at 7:17 am, there was no longer a 67 degree azimuth by which to determine a “157/337” line of position (LOP). It simply no longer existed. It lasted only an hour-plus. After that, she could only fly a heading of 157 or 337 degrees.

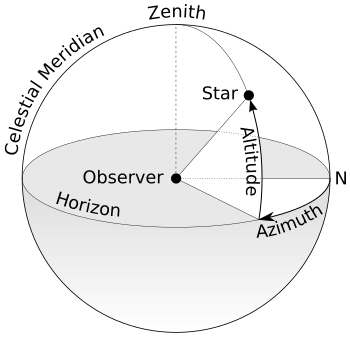

(Editor’s Note: As a non-aviation type, I’m lost when Calvin starts using terms such as azimuth. For others like myself and for what it’s worth, Wikipedia (image above) defines azimuth as an angular measurement in a spherical coordinate system. The vector from an observer (origin) to a point of interest is projected perpendicularly onto a reference plane; the angle between the projected vector and a reference vector on the reference plane is called the azimuth. Calvin will provide clarity in Part II.

(End Part I)

Grounds for a Possible Search for Amelia Earhart: E.H. Dimity’s 1939 argument for new search, Part I

The author of today’s disputation, E.H. “Elmer” Dimity, was a parachute manufacturer during the late 1930s who knew Amelia and established an Amelia Earhart Foundation following her disappearance in hopes of organizing a new search. Though not a well-known figure in Earhart lore, Dimity owned the only autographed souvenir envelope, or stamped flight cover, known to have survived Earhart’s 1937 round-the-world flight, because it actually didn’t accompany her in her Electra.

The Sept. 13, 1991 New York Times, Auctions Section, page 00015, in a brief titled “Airmail,” explains:

On March 17, 1937, when Earhart left Oakland, Calif., on her first attempt to circle the globe, the envelope was in one of the mail packages aboard her plane. The plane’s landing gear gave way in Honolulu, and when the plane was sent back to Oakland for repairs, the mail was returned with it. Before Earhart left again on May 21, the damaged mail packages were re-wrapped under the direction of the Post Office. It was then, Elmer Dimity reported later, that he removed the envelope as part of a joke he planned to play when Earhart returned. He said he had hoped to meet her with the envelope in hand, saying the mail had arrived before she did.

“Mr. Dimity sold the envelope in the 1960s on behalf of the Amelia Earhart Foundation to a dealer,” said Scott R. Trepel, a Christie’s consultant, who organized the auction house’s sale. The collector who bought the envelope from that dealer is the unidentified seller of the Earhart memento, which is to be sold with an affidavit from Mr. Dimity. Christie’s estimates that the envelope will bring $20,000 to $30,000.

Close-up view of Amelia Earhart receiving the last package of flight covers from Nellie G. Donohoe, Oakland Postmaster. At left is Paul Mantz, Earhart’s co-pilot as far as Honolulu. Behind Mrs. Donohoe is E. H. Dimity, ca. March 17, 1937.

In perhaps the best Earhart biography, The Sound of Wings (1989), author Mary Lovell discusses Dimity and his ineffective foundation briefly, but for now we turn our attention to his 1939 paper, “Grounds for a Possible Search for Amelia Earhart,” which appeared in the August 1994 issue of Bill Prymak’s Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters.

“Grounds for a Possible Search for Amelia Earhart” (Part I of Two)

by E.H. Dimity, August 1939

Walter McMenamy was thoroughly familiar with Miss Earhart’s voice. He knew it perfectly, could detect it when others heard but a jumble of sound. This was proven during earlier flights. His familiarity with the Earhart voice began in January 1935, when Miss Earhart made her solo flight to the mainland. During this flight, McMenamy was the only radio receiver in constant touch with her ship, working with station KFI in Los Angeles which was broadcasting to her plane. His work on this flight brought warm and written recognition from both the station and Miss Earhart. His set, built for experimentation in a laboratory, was the only one which reported her position through this flight, bringing in the signals when the equipment of the station itself could not do so.

The hope that Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Capt. [sic] Fred Noonan may be found alive on some tiny island in the South Pacific is a thrilling hope, one that awakens sentiment in the American public who knew her as the heroine of the skies, and particularly strikes a sentimental chord in those who knew her before her disappearance.

There would be sadness in the thought, too, for she has been given up, long since. The hope would appear to be vain, born of wistful thinking. But there are cold, indisputable facts which have never been made public, and which must demonstrate to anyone of open mind that no sufficient search was ever made for Miss Earhart and Capt. Noonan, and that either they are now alive on land in the lonely, untraveled nowhere of their disappearance, or have died since, praying that they would be found.

It is the purpose of this brief memorandum to state these facts, in their order and without elaboration, and to let them argue the case for a new search.

The “Round-the-World Flight” cover made famous by Amelia Earhart. All the originals save one disappeared with the Earhart plane on July 2, 1937. (Purdue University Libraries, Archives and Special Collections.)

Before offering the evidence, however, it might be well to list those who believe that either Miss Earhart may be found alive, or that evidence to solve the mystery may be found, and that a new search should be made as soon as possible.

This group includes the following:

Amelia Earhart’s mother, who has made an intimate study of the data and believes steadfastly that her daughter will be found.

Clarence A. Williams, pilot and navigator who charted Miss Earhart’s course around the world.

Paul Mantz, Miss Earhart’s flying instructor and friend, who accompanied her on her flight to Honolulu.

Margot DeCarie, Amelia Earhart’s secretary.

E.H. Dimity, longtime friend of Miss Earhart, who took care of many details for her in planning her flights, and who once refused to let her pilot his plane because she was just learning to fly then. Mr. Dimity established, and is the President of the Amelia Earhart Foundation [now defunct], in Oakland, Calif.

Walter McMenamy, radio expert who was in constant touch with her by air on her solo flight from Honolulu to the mainland, and who probably saved her life by quick thinking on that occasion, when she was flying off her course. McMenamy also helped guide by radio the first Clipper ship flight to Honolulu. He charted Miss Earhart’s radio course around the world, and heard her last signals. [Editor’s note: Pure speculation. See my April 30, 2014 post, “Earhart’s ‘post-loss messages’: Real or fantasy?”]

West Coast amateur radio operators Walter McMenamy (left) and Carl Pierson, circa 1937, claimed they heard radio signals sent by Amelia Earhart, including two SOS calls followed by Earhart’s KHAQQ call letters.

The reader, perhaps surprised at the suggestion that there may be good reasons for believing Miss Earhart still alive, no doubt will have many questions in his mind, which this memorandum will seek to answer. Some of these questions are:

1. Didn’t Navy and Coast Guard search the area where she might have gone down, completely and fruitlessly?

2. If she landed on an island, how could Miss Earhart and Capt. Noonan be alive now, without food or water?

3. If they are still alive, why have they not been heard from?

The first important fact to be recorded was known to only a few at the time of Miss Earhart’s flight and disappearance, has never been made generally known to the public, and is of tremendous importance. This fact is that Miss Earhart’s plane and radio equipment were such that the plane could broadcast only from the air or while on land. The plane could not have broadcast from water. This is proven not only by the testimony of those who helped in the flight preparations, but by the Lockheed factory which made the plane, and by the radio experts who installed the equipment. The radio transmitter had to be powered by the motor generator, which would be submerged and inactive in the water.

The importance of this fact is, briefly, that it can be proven beyond doubt that the Earhart plane DID broadcast radio signals many hours after it had to be down somewhere, and the plane must have been on land.

The third fact is that radio signals were received from the Earhart plane days after it had landed. These signals were heard in various parts of the world, by several radio operators, including ships at sea, government stations, and her radio contact man, Walter McMenamy. Proof of this is in official records and affidavits. These signals, and the time they were heard, will be described later.

These facts can and will be proven, and they lead directly to the conclusion that the Earhart plane landed in a place not searched, and must be still there with its occupants alive or dead. Their last radio signal had a decided ripple or sputter, which any radio expert recognizes immediately as evidence that the power was failing.

Immediately two questions arise. First, what chance could they have for survival on a tiny, deserted island, with little food and no water? History provides an answer. There are many cases on record where persons shipwrecked, stranded, and believed lost were found years later, alive, in this same area where the Earhart plane landed. One party, without food, lived on fish, shellfish, and bird’s eggs, and captured rainwater for drinking. A monotonous diet, but they survived and were rescued from an island which appeared to be incapable of sustaining life.

The second question is: If they were safe, why have they not been picked up, or heard from? There is a single answer to this. Their course took them over a sea area strewn with hundreds of islands, which had never been seen from the air, and parts of which have never been visited by civilized man. Hundreds of miles from the steamer lanes, thousands from communication. Many of the islands, on their course have never been charted, and appear on no map.

Amelia with Bendix Corporation representative Cyril Remmlein, and the now-infamous direction finding loop that may or may not have failed her during the final flight. (Photo courtesy Albert Bresnik, taken from Earhart’s Flight Into Yesterday, by Laurance Safford, Robert Payne and Cameron Warren.)

What could anyone do but wait, and pray for rescue?

To complete the story, let’s review the events of the disappearance and search point by point.

Miss Earhart and Capt. Noonan had an excellent aircraft, a Lockheed Electra, powered with two 550-horsepower motors and equipped with the latest instruments devised. They cruised at an average speed of 150 mph. At no time during the flight, even when their gas supply was running low and they were lost, did they report any trouble of any kind, with the motor or otherwise. No wreckage of the plane has ever been sighted or found, no evidence of an explosion or a sudden crash into the sea caused by faulty motors.

The two left Miami, Florida, on their flight around the world June 1, 1937. The first leg of the trip to South America was completed without difficulty. On their flight 1,900 miles across the South Atlantic to Africa, it was reported that the plane’s radio did not function properly, but the span was successfully accomplished. The trip then took them across Africa and to India. In the Bay of Bengal, the plane encountered a monsoon which forced it close to the water, but their objective was won, and the fliers safely reached Lae, British New Guinea.

At Lae they drew breath for the most difficult leg of the trip, one never before attempted. This was a 2,570- [exactly 2,556] mile flight from Lae to Howland Island, a distance greater than from Los Angeles to New York, over a lonely, poorly charted sea. The navigation must be perfect, for they were aiming at a pinpoint in the ocean, tiny Howland Island less than two miles square and 20 feet above sea level at its highest point. Their aim, at such a distance, must be flawless.

Few navigators would stake their lives, as Capt. Noonan did, on such a gamble.

Navigators say that even with the gentle prevailing winds that were blowing at the time, a drift of ten degrees off course in such a distance might easily occur, even with the most expert navigation.

If the plane did drift, from its last know bearing, it might have come down somewhere in a triangle stretching nearly 1,500 miles long and about 500 miles wide at its base. This fateful triangle includes nearly a million square miles and hundreds of unexplored islands, and only a small part of it has ever been searched for the missing pair.

Miss Earhart and Capt. Noonan took off from Lae on the morning of July 1, Pacific Standard Time [10 a.m., July 2, Lae Time]. The first 500 miles of their flight took them over sea and islands fairly well known, where they could take bearings without difficulty. Shortly after 5 p.m., they reported they were 725 miles out, and directly on course. Although regular broadcasts were heard from the plane hours later, this was the last position definitely reported, and our triangle starts from the 800-mile mark, for these reasons.

Radio room of USCG Cutter Tahoe, sister ship to Itasca, circa 1937. Three radio logs were maintained during the flight, at positions 1 and 2 in the Itasca radio room, and one on Howland Island, where the Navy’s high-frequency direction finder had been set up. Aboard Itasca, Chief Radioman Leo G. Bellarts supervised Gilbert E. Thompson, Thomas J. O’Hare and William L. Galten, all third-class radiomen, (meaning they were qualified and “rated” to perform their jobs). Many years later, Galten told Paul Rafford Jr., a former Pan Am Radio flight officer, “That woman never intended to land on Howland Island!”

The last 1,000 miles of the flight were the most difficult. There were no landmarks to aid in navigation, and the slightest drift off course could take them miles from their destination.

Stationed at Howland Island to aid the flight was the Coast Guard cutter Itasca, to keep in radio contact with the ship and to advise on weather. Miss Earhart’s radio could transmit on two wave lengths, 3105 kilocycles and 6210 kilocycles. There was only one thing wrong with the arrangements, and this mistake may be the cause, perhaps, for the disaster.

Although the Itasca had a radio direction finder which would show the course of signals it received, and thus make it possible to give bearings to a lost plane, the direction finder could not work on the Earhart wavelengths.

Miss Earhart, in the last desperate hours of her flight, asked the Itasca again and again to give her a report on her position. Evidently she did not know the Itasca was not equipped with a direction finder which could aid her.

An ironic comment can be made here of the flight preparations at Lae. During the earlier part of her trip, Miss Earhart’s plane was equipped with a “trailing antenna.” This wire trailing under the plane made it possible for the plane to broadcast on the regular ship wavelength of 500 meters (kc). With the trailing antennae, she could have transmitted signals on that wavelength, and the Itasca direction finder, tuned to this frequency, could have reported her position in the air. But, for mysterious reasons, Miss Earhart left the trailing antennae at Lae [most say Miami]. Then she canceled, irrevocably, her chance to learn from the Itasca or other ships where she was, lost in the skies seeking tiny Howland Island. The Itasca direction finder could not help her.

(End of Part I)

Earhart’s “Disappearing Footprints,” Part III

Today we move along to Part III of Capt. Calvin Pitts’ “Amelia Earhart: DISAPPEARING FOOTPRINTS IN THE SKY,” his studied analysis of Amelia Earhart’s final flight. We left Part II with Calvin’s description of the communication failures between the Navy tug USS Ontario and the ill-fated fliers.

“What neither of them knew at that time was the agonizing fact that the Electra was not equipped for low-frequency broadcast,” Calvin wrote, “and the Ontario was not equipped for high-frequency. . . . After changing frequencies to one that the Ontario could not receive, it is safe to assume that Amelia made several voice calls. Morse code, of course, was already out of the picture.”

We’re honored that Calvin has so embraced the truth in the Earhart disappearance that he’s spent countless hours working to explain the apparently inexplicable — how and why Amelia Earhart reached and landed at Mili Atoll on July 2, 1937. Here’s Part III, with even more to follow.

“Amelia Earhart: DISAPPEARING FOOTPRINTS IN THE SKY, Part III”

By Capt. Calvin Pitts

Although Amelia was obviously trying to make contact with the Ontario by radio, Lt. Blakeslee did not know that. By the same token, Amelia had to wonder why he would not answer.

USS Ontario (AT-13), was a Navy tug servicing the Samoa area, but assigned to the Earhart flight twice as a mid-point weather and radio station for assistance.

This failure to communicate, however, worked into Amelia’s new plan. Since she had no way of letting the Ontario know they were en route, being without Morse code and having frequencies which were not compatible, now that he had been plying those waters for 10 days along her flight path, she knew it was useless to try to find and to overfly the unknown position of the Ontario in the thick darkness of a Pacific night.

Therefore, it now made even more sense to continue on to Nauru whose people had been alerted by Balfour that the Electra was probably coming. Although that had begun as a suggestion, no one yet knew that it had now become a decision. She needed to let the Ontario know — but how?

She had lost contact with Balfour, couldn’t make contact with the Ontario, and the Itasca had not yet entered the picture. Nauru, it was later learned, had a similar problem as the Ontario, and Tarawa had not broadcast anything. Amelia was good at making last-minute decisions. “Let’s press on to Nauru,” she might have said. “It’s a small diversion, and a great gain in getting a solid land-fix. I’ll explain later.”

The local chief of Nauru Island, or someone in authority, already had a long string of powerful spot lights set up for local mining purposes. He would turn them on with such brightness, 5,000 candlepower, that they could be seen for more than 34 miles at sea level, even more at altitude.

Finding a well-lit island was a sure thing. Finding a small ship in the dark ocean, which had no ETA for them, was doubtful. Further, as was later learned from the Ontario logs, the winds from the E-NE were blowing cumulus clouds into their area, which, by 1:00 a.m. were overcast with rain squalls. It is possible that earlier, a darkening sky to the east would have been further assurance that deviating slightly over Nauru was the right decision.

As the Electra approached the dark island now lit with bright lights, Nauru radio received a message at 10:36 p.m. from Amelia that said, “We see a ship (lights) ahead.”

Others have interpreted this as evidence that Amelia was still on course for the Ontario, and was saying that she had seen its lights. The conflict here is that Amelia flew close enough to Nauru for ground observers to state they had heard and seen the plane. How could Amelia see Nauru at the same time she saw the Ontario more than 100 miles away?

Amelia may have wondered if Noonan and Balfour were wrong about Nauru. But they weren’t. According to the log from a different ship coming from New Zealand south of them, they were en route to Nauru for mining business. Those shipmates of the MV Myrtlebank, a 5,150 ton freighter owned by a large shipping conglomerate, under the British flag, recorded their position as southwest of Nauru at about 10:30 pm on that date. The story of the Mrytlebank fits in well to resolve this confusion. It was undoubtedly this New Zealand ship, not the Ontario, that Amelia had seen.

Those shipmates of the MV Myrtlebank, a 5,150 ton freighter owned by a large shipping conglomerate, under the British flag, recorded their position as southwest of Nauru at about 10:30 pm on that date. The story of the Mrytlebank fits in well to resolve this confusion. It was undoubtedly this New Zealand ship, not the Ontario, that Amelia had seen.

MV Myrtlebank, a freighter owned by Bank Line Ltd., was chartered to a British Phosphate Commission at Nauru. As recorded later, around 10:30 p.m., third mate Syd Dowdeswell was “surprised to hear the sound of an aircraft approaching and lasting about a minute. He reported the incident to the captain who received it ‘with some skepticism’ because aircraft were virtually unknown in that part of the Pacific at that time. Neither Dowdeswell nor the captain knew about Earhart’s flight.”

Source: State Department telegram from Sydney, Australia dated July 3, 1937: “Amalgamated Wireless state information received that report from ‘Nauru’ was sent to Bolinas Radio ‘at . . . 6.54 PM Sydney time today on (6210 kHz), fairly strong signals, speech not intelligible, no hum of plane in background but voice similar that emitted from plane in flight last night between 4.30 and 9.30 P.M.’ Message from plane when at least 60 miles south of Nauru received 8.30 p.m., Sydney time, July 2 saying ‘A ship in sight ahead.’ Since identified as steamer Myrtle Bank (sic) which arrived Nauru daybreak today.”

“Unless Mr. T.H. Cude produced the actual radio log for that night, the contemporary written record (the State Dept. telegram) trumps his 20-plus-year-old recollection.”

The MV MYRTLEBANK of the BANK LINE Limited was about 60 nautical miles southwest of Nauru Island when it entered the pages of history. Amelia Earhart said, “See ship (lights) ahead.” This was most likely that ship since the Ontario would have been 80 to 100 miles away. Nauru, the destination of this ship, was lit with powerful mining lights. At Nauru Island, the Electra would be eight-plus hours from “Area 13,” or 2013z (8:43 am) 150-plus miles from Howland Island.

This was most likely the ship about which Amelia Earhart said: “See ship (lights) ahead.” Most researchers state that she had spotted the USS Ontario, which had been ordered by the Navy to be stationed halfway between Lae and Howland for weather information via radio. No radio contact was ever made between Amelia’s Lockheed Electra 10E and the Ontario.

While it is possible that Amelia flew only close enough to Nauru to see the bright mining lights, it is more likely that a navigator like Noonan would want a firm land fix on time and exact location.

For this reason, in a re-creation of the flight path on Google Earth, which we have done, we posit the belief, in view of the silence from the Ontario, that having a known fix prior to heading out into the dark waters, overcast skies and rain squalls of the last half of the 2,556-mile (now 2,650-mile) trip to small Howland, it was the better part of wisdom to overfly Nauru.

Weather and radio issues were the motive behind Harry Balfour’s suggestion to use Nauru as an intermediate point rather than a small ship in a dark ocean. Thus, the Myrtlebank unwittingly became part of the history of a great world event.

Now, with the land mass of Nauru under them, Fred could begin the next eight hours from a known position. Balfour’s suggestion and Fred and Amelia’s decision was not a bad call, with apologies to the crew of the Ontario. Unfortunately, it was not until after the fact that the Ontario was notified of this. They headed back to Samoa with barely enough coal to make it home. Lt. Blakeslee said they were “scraping the bottom” for coal by the time they returned.

The details of the eight-hour flight from Nauru are contained in the Itasca log. In my own case, the Amelia story was interesting, but not compelling. However, it was not until I began to study in minute detail the Itasca logs of those last hours of the Electra’s flight, hour by hour, and visualizing it by means of Google Earth, that the interest turned to a passion.

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED? DO WE HAVE ENOUGH EVIDENCE TO KNOW? IS THERE REALLY NO ANSWER TO WHAT HAS BEEN CONCEALED AS A “MYSTERY”?

In the reliving of what was once a mystery, things began to make sense, piece by piece. It was like being a detective who knew there were hidden pieces, but what were they, and where did they fit? For me, as the puzzle began to come together, the interest grew. There is really more to this story, much more, than appeared during the first reading.

Itasca Chief Radioman Leo Bellarts and three other Coast Guard radiomen worked in vain to bring Amelia Earhart, Fred Noonan and the Electra to a safe landing at Howland Island. Photo courtesy Dave Bellarts.

The radio room positions and pages being logged contained valuable information. Reading the details created a picture in the imagination at one level, but with more and more evidence piling up, a different level began to emerge.

Can this story really be true? Credulity was giving way to the reality of evidence.

If you will follow the highlights of the Itasca logs, you may find yourself captivated, as I was. One thing that is not spoken at first, but becomes a message loud and clear, is the not-so-hidden narrative in those repeated, unanswered Morse code transmissions.

The radiomen thought they were helping Amelia and Fred, but with each unanswered Code message, they were really just talking to themselves. As they get more desperate, you keep wondering: Surely the Electra crew can at least “hear” the clicks and clacks, the dits and dahs, even if they don’t fully understand them.

Why don’t they at least acknowledge they hear even though understanding appears to be absent? Why the silence, the long silence into the dark night, the silence which leaves the Itasca crew bewildered, even “screaming,” as they later said, “into the mike?”

The Coast Guard Cutter Itasca was anchored off Howland Island on July 2, 1937 to help Amelia Earhart find the island and land safely at the airstrip that had been prepared there for her Lockheed Electra 10E.

The position of the Electra, an “area,” not a fix, is our primary destination now because Howland was never seen. This makes Howland secondary for this exercise, mostly because that was not the position from which Amelia made her final and fatal decision.

There were at least two extremely dangerous elements involving Howland, and one strategic matter. Dangerous: 10,000 nesting and flying birds waiting to greet Mama big bird, and the extremely limited landing area of a 30 city-block by 10-block sand mass.

We delay our discussion about “strategic” since it deals with the government hijacking of a civilian plane, something controversial but which is worth waiting for. Stand by.

For now, we join Amelia and Fred for some details of their flight to “Area 13.” The purpose here is to locate, as best we can, that area from which Amelia made her final navigation decision.

That area encompasses a portion of ocean 200 miles by 200 miles. South to north, it begins about 100 miles north of Howland to at least 300 miles north. East to west, it begins with a NW line of 337 degrees and continues west parallel to that line for at least 200 miles.

There is a mountain of calculation behind that conclusion, but those details are for another venue. For now, for those interested in re-creating that historic flight, especially if you have Google Earth, follow the Itasca log in order to see Google Truth.

We designate this 200 by 200 miles as “Area 13” for the simple reason that their last known transmission not within sight of land which can be confirmed was at 2013z (GMT) (the famous 8:43 am call). Following this was nothing but silence for those on the ground.

After their long night of calling, waiting and consuming coffee, for the crew of Itasca and Howland Island, 8:43 a.m. was a special time. But 2013 GMT (8:43 a.m.) was also the 20-hour mark for the fliers, after their own, even more stressful all-nighter. Sadly, the two in the Electra, at 13 past 20 hours, were entirely on their own at 2013 — and here that sinister number “13” appears again.

Radio room of USCG Cutter Tahoe, sister ship to Itasca, circa 1937. Three radio logs were maintained during the flight, at positions 1 and 2 in the Itasca radio room, and one on Howland Island, where the Navy’s high-frequency direction finder had been set up. Aboard Itasca, Chief Radioman Leo G. Bellarts supervised Gilbert E. Thompson, Thomas J. O’Hare and William L. Galten, all third-class radiomen, (meaning they were professionally qualified and “rated” to perform their jobs). Many years later, Galten told Paul Rafford Jr., a former Pan Am Radio flight officer, “That woman never intended to land on Howland Island.”

The following routing and times are a compilation from several sources:

(1) Itasca Logs from the log-positions on the ship, a copy of which can be provided;

(2) Notes from Harry Balfour, local weather and radioman on site at Lae;

(3) Notes from L.G. Bellarts, Chief Radio operator, USS Itasca;

(4) The Search for Amelia Earhart, by Fred Goerner;

(5) Amelia Earhart: The Truth At Last, by Mike Campbell;

(6) David Billings, Australian flight engineer (numbers questionable), Earhart Lockheed Electra Search Project;

(7) Thomas E. Devine, Vincent V. Loomis, and various other writings.

The intended course for the Electra was a direct line from Lae to Howland covering 2,556 statute miles. The actual track, however, was changed due to weather, in the first instance, and due to a change of decision in the second instance. Such contact never took place. Neither the Electra nor the Ontario saw nor heard from the other, for reasons which could have been avoided if each had known the frequencies and limitations of the other. This basic lack of communication plagued almost every radio and key which tried to communicate with the Electra.

If one has access to Google Earth, it is interesting to pin and to follow this flight by the hour. The average speeds and winds were derived from multiple sources, including weather forecasts and reports.

To generalize, the average ground speed going east was probably not above 150 mph, with a reported headwind of some 20 mph, which began at about 135-140 mph when the plane was heavy and struggling to climb.

In the beginning, with input from Lockheed engineers, Amelia made a slow (about 30 feet per minute) climb to 7,000 feet (contrary to the plan laid out by Lockheed’s Kelly Johnson), then to 10,000 feet (which should have been step-climbing to 4,000 to 7,000 to 10,000 feet toward the Solomons mountain), then descending to 8,000 feet depending upon winds, then to 10,000 feet reported, with various changes en route.

The remaining contingency fuel at 8:43 a.m. Howland time, to get the Electra back to the Gilbert Islands, as planned out carefully with the help of Gene Vidal (experienced aviator) and Kelly Johnson (experienced Lockheed engineer), has often been, in our opinion, mischaracterized and miscalculated. By all reasonable calculations, the Electra had about 20 hours of fuel PLUS at least four-plus hours of contingency fuel.

July 2, 1937: Amelia Earhart, leaving Lae, New Guinea, frustrated and fatigued from a month of pressure, problems, and critical decisions on a long world flight, and unprepared for the Radio issues ahead, unprepared, that is, unless there was a bigger plan in play.

Then why did Amelia say she was almost out of fuel when making one of her last calls at 1912z (7:42 am)? Obviously, she was not because she made another call an hour later about the “157-337 (sun) line” at 2013z. Put yourself in that cockpit, totally fatigued after 20 hours of battling wind and weather and loss of sleep, compounded by 30 previous difficult days. It is easy to see four hours of fuel, after such exhaustion, being described as “running low.”

With the desperation of wanting to be on the ground, it would be quite normal to say “gas is running low” just to get someone’s attention. If one is a pilot, and has ever been “at wit’s end” in a tense situation, they have no problem not being a “literalist” with this statement. The subsequent facts, of course, substantiate this.

An undated view of Howland Island that Amelia Earhart never enjoyed. Note the runway outline many years later, a destination which became a ghost. In the far distance to the left, under thick clouds at 8:13 a.m. local time, was “Area 13.”

Wherever the Electra ended up, and we have a volume of evidence for that in a future posting, IT WAS NOT IN THE OCEAN NEAR HOWLAND. That was a government finding as accurate and as competent as the government’s success was against the Wright Brothers’ attempt to make the first fight.

For this leg of the Electra’s flight to its destination, our starting data point was Lae, New Guinea, and our terminal data point is not the elusive bird-infested Howland Island, but rather the area where they were often said to be “lost,” a place we have designated as Area 13. (A more detailed flight, by the hour with data from the Itasca logs, is available. Enjoy the trip.

Summary of track from Lae to Area 13 then to Mili Atoll (times are approximate):

(1) LAE to CHOISEUL, Solomon Islands – Total Miles: 670 / Total Time: 05:15 hours

(2) CHOISEUL to NUKUMANU Islands – Total Miles: 933 / Total Time: 07:18 hours

(3) NUKUMANU to NAURU Island – Total Miles: 1,515 / Total Time: 11:30 hours

(4) NAURU to 1745z (6:15 a.m. Howland) – Total Miles: 2,440 / Total Time: 17:45 hours

(5) 1745z to 1912z (7:12 a.m. Howland) – Total Miles: 2,635 / Total Time: 19:12 hours

(6) 1912z to 2013z (8:43 a.m. Howland) – Total Miles: 2.750 / Total Time: 20:13 hours

LAE to AREA 13: Total Miles : 2,750 (Including approaches) Time: About 20:13 hours

Fuel Remaining: About 4.5 to 5 hours

Distance from 2013z to Mili Atoll Marshall Islands = About 750 miles

Ground speed = 160 (true air speed) plus 15 mph (tailwind) = 175 mph

Time en route = About 4.3 hours

ETA at Mili Atoll, Marshall Islands = Noon to 12:30; Fuel remaining: 13 drops

NOTE that from a spot about 200 mi NW of Howland (Area 13) to the Gilberts is not the same heading as to the Marshall’s Mili Atoll. The Gilberts are the three small islands below Mili Atoll. The “Contingency Plan” was to return to the Gilberts and land on a beach among friendly people. Instead, they made an “intentional” decision to pick up a different heading toward the Marshalls whose strong Japanese radio at Jaluit they could hear. Compare the two different headings from Area 13 to the Gilberts and to the Marshalls. The difference is about 30 degrees. THEY ARE NOT THE SAME. Did they make an honest mistake, or an intentional decision?

The heading to the Gilberts would not have taken them to the Marshall Islands, with a heading difference of about 30 degrees. The decision to give up on Howland, and utilize the remaining contingency fuel was “intentional,” not merely intentional to turn back, but to turn toward the Marshalls where there was a strong radio beam, a runway, fuel — and Japanese soldiers who may or may not be impressed with the most famous female aviator in the world. Amelia and her exploits were known to be popular in Japan at that time. Although their mind was on war with China, maybe this charming pilot could tame them.

Unfortunately, we know THE END of the Amelia story, and it was not pretty. When she crossed into enemy territory, she apparently lost her charm with the war lords, and eventually her life. (End of Part III.)

Next up: Part IV of “Amelia Earhart: Disappearing Footprints in the Sky.” As always, your comments are welcome.

![Fishing boat story 5 This story appeared at the top of page 1 in the July 13, 1937 edition of the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania)-Globe Times. “Vague and unconfirmed rumors that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan have been rescued by a Japanese fishing boat without a radio,” the report began, “and therefore unable to make any report, found no verification here today, but plunged Tokio [sic] into a fever of excitement.” The story was quickly squelched in Japan, and no follow-up was done. (Courtesy Woody Peard.)](https://i0.wp.com/earharttruth.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/fishing-boat-story-5.png?w=616&h=352&ssl=1)

Recent Comments