Noted Earhart book review removed from Internet

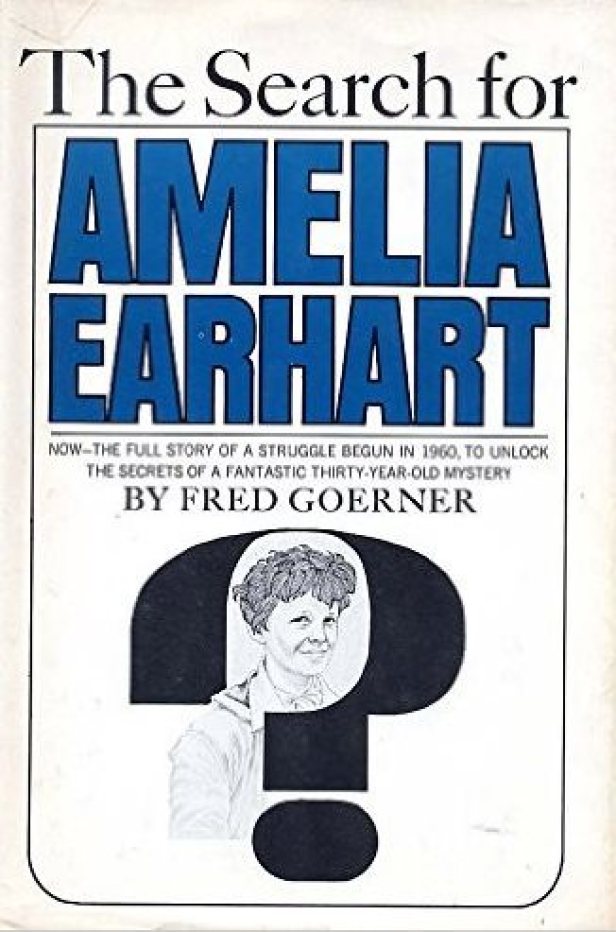

In the entire history of reviews of the handful of books that present aspects of the truth in the Earhart disappearance, only two are memorable. The first was the Sept. 16, 1966 Time magazine unbylined attack against Fred Goerner’s The Search for Amelia Earhart, titled “Sinister Conspiracy?” and still available online, though you have to subscribe to the source to see it now. My commentary about Time’s hit piece, “The Search for Amelia Earhart”: Setting the stage for 50 years of media deceit,” was posted June 21, 2016; you can read it by clicking here. Goerner, a KCBS radio personality in San Francisco, was the only real newsman to ever seriously investigate the Earhart case.

The only other significant review of an Earhart disappearance work was Jeffrey Hart’s examination of Vincent V. Loomis’ Amelia Earhart: The Final Story, which appeared in William F. Buckley’s National Review in the Oct. 18, 1985 issue, but is no longer available online.

Hart wasn’t an Earhart researcher, and his belief about the reason Earhart reached Mili is the same pure speculation that Loomis advanced. But Hart was a well-known establishment pundit, critic and columnist, and wrote for National Review for more than three decades, where he was senior editor. He wrote speeches for Ronald Reagan while he was governor of California, and for Richard Nixon. Now 88, Jeffrey Hart is professor emeritus of English at Dartmouth College, in Hanover, New Hampshire. No one of similar stature has ever written a review of an Earhart disappearance book.

I’ll have a bit more to say, but here is Jeffrey Hart’s review of Amelia Earhart: The Final Story, originally titled “The Rest of the Story.” Boldface emphasis is mine throughout.

AS A BOY I was thrilled with horror when Amelia Earhart disappeared somewhere out over the Pacific during the summer of 1937. She had been the first woman to fly the Atlantic, and now she and her navigator were trying to circle the globe at the equator. She rather disliked being called “Lady Lindy” by the press, because she wanted her own independent identity, but the odd thing was that she looked a little like Lindbergh: thin, with short hair and a wide grin, somehow quintessentially American.

Vincent V. Loomis’ 1985 book is among the most important ever written about the disappearance of Amelia Earhart, and solidly established her presence, along with Fred Noonan, in the Marshall Islands soon after their July 2, 1937 disappearance.

On her last flight she and her navigator Fred Noonan, flew an advanced-model twin-engine aluminum Electra specially designed for the trip. It was known to the press as the “Flying Laboratory.” On July 2, 1937, all contact with the plane was lost, and searches by U.S. ships and planes failed to turn up any trace of Miss Earhart, Noonan, or the plane. As far as anyone at the time knew, they had simply disappeared into that vast blueness, like Hart Crane off the Orizzaba.

It turns out that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan were the first casualties of the coming Pacific war with the Japanese. Vincent Loomis, a former USAF pilot with extensive Pacific experience, became fascinated with the Earhart mystery and made it his business to solve it, which he had done. It is a remarkable, enormously romantic, and heartbreaking story. Loomis went to the Pacific, traveled around the relevant islands, and found natives who had seen the plane crash and had seen Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan. He interviewed the surviving Japanese who were involved, and he photographed the hitherto unknown Japanese military and diplomatic documents. The mystery is a mystery no longer.

For all her frame and accomplishments, Amelia Earhart was an innocent flying out over the Pacific. She and Noonan were also incompetent navigators and did not know how to work their state-of-the-art equipment. They were thus more than a hundred miles off course flying right into the middle of the secret war plans of the Japanese empire* when they ran out of fuel and had to ditch the Electra. (Editor’s note: Amelia never claimed to be a navigator at all, but Noonan was recognized as among the best in the world at the time of the final flight.)

By 1937 the Japanese had long since concluded that war with the United States for control of the western Pacific was inevitable. They were hatching plans with Hitler to divide up the British, French, and Dutch possessions that would be vulnerable as a result of the coming European war. The projected Japanese empire, the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, would have its large mainland anchor in a China the Japanese were attempting to conquer, and The Pacific islands would be the first line of defense against the U.S. Navy. The Japanese knew that the United States was unlikely to tolerate their geopolitical plans and would be decidedly hostile to any monopolistic co-prosperity sphere run from Tokyo.

The Japanese had acquired control of the key Pacific islands at the end of World War I under a League of Nations mandate. In violation of international law, they were pouring military resources into them. All Japanese military personnel worked in civilian clothes. Newly paved airstrips were marked as “farms” on the maps. Foreign visitors were absolutely excluded. If the local natives obeyed the Japanese rules they were treated fairly, and the Japanese even married some of them. An infraction, however, could mean instant death.

Jeffrey Hart, undated, from Hart’s Wikipedia page.

On July 2, 1937, bewildered and lost, Amelia Earhart crash-landed in the middle of all this, putting the Electra down and running into an atoll near Mili Mili a principal military position in the Japanese Marshall Island chain. The Japanese took her and Noonan prisoner and tried to figure out what to do with them. They could hardly release them, not knowing what they had seen. Perhaps the American fliers could blow the whistle on the whole secret operation. They might even be spies. Actually, they had seen nothing.

The two Americans were shipped to Japanese military headquarters on Saipan and jailed. The conditions were miserable, but not unusual for that time and place. The jail was not set up to serve food to the prisoners, mostly natives, whose meals were brought to them by relatives. But the jailers did provide the two Americans with soup, fish, and so forth, though of very poor quality, and with medical treatment. When an exasperated Fred Noonan threw a foul bowl of soup at a Japanese jailer, he was forced to dig his own grave and was immediately beheaded. Japanese culture was not especially permissive in 1937.

After a while, Miss Earhart was allowed a limited amount of freedom and made friends with native families, some of whom Loomis interviewed. She was permitted visits to these friends, and her diet and spirits improved. In mid-1938, however, life in the tropics proved too much for her and she came down with a severe case of dysentery, weakened rapidly, and died there on Saipan. She does not seem to have grasped the significance of what she had stumbled upon and witnessed; ironically enough, she was a philosophical pacifist. The Japanese military asked the natives to provide a wreath for her, and she was buried with Noonan.

Vincent V. Loomis at Mili, 1979. In four trips to the Marshall Islands, Loomis collected considerable witness testimony indicating the fliers’ presence there. His 1985 book, Amelia Earhart: The Final Story, is among the most important of the Earhart disappearance books, in that it established the presence of Amelia and Fred Noonan at Mili Atoll in the Marshall Islands following their disappearance on July 2, 1937. (Courtesy Clayton Loomis.)

One curious footnote to the story is that the present Japanese government, democratic and pro-Western as it supposedly is, has been covering the whole thing up. Today’s Tokyo will not admit, in the face of absurdly obvious proof, that the imperial government was violating the terms of its mandate by militarizing the islands, claiming that everything the islands, claiming that everything going on had to do with “culture” and fishing — no one here but us Japanese Margaret Meads and a few fishing boats. Nor will today’s Tokyo admit that the imperial government lied fifty years ago when it covered up the Amelia Earhart matter. Of course no U.S. Navy search vessels were allowed anywhere near the Marshall Islands. The Japanese claimed that they themselves were doing all the necessary searching. Loomis shows that the “search ships” were in Tokyo Bay at the time. It is odd that the present government cannot admit to the demonstrable facts; it must represent some sort of face-saving. But Tokyo has run out of luck on this one. Vincent Loomis has the documents, the testimony of the Pacific islanders, local Catholic nuns, Japanese medics and seamen.

It is all very poignant. One sees that the Japanese military among whom Amelia Earhart lived for about a year could not begin to comprehend her, this woman pilot, this . . . American. But the evidence is that the Japanese who knew her, if from a very great cultural distance, nevertheless bemusedly admired her. (End of Hart review.)

Hart wrote an accurate, unbiased review of The Final Story, but neither the U.S. government or anyone else in the media got his memo that “the mystery is a mystery no longer.” Not only did they disagree, and still do, but Hart’s review has been expunged from the Internet, where the hard copy I have was taken from Encyclopedia.com in 2007. I don’t know when the review was removed, but there’s no doubt about why it’s gone, and I’m not going to repeat here how sacred cows get even more revered and protected with age.

Within the past year, plugging the name Amelia Earhart into the Amazon.com search engine has resulted in over 1,500 results for books; recently, for some unknown reason, that number has fallen to “over 1,000” in the same category. Nevertheless, many books have been penned about our ageless American heroine, but of these thousand or so, only about 10 actually present aspects of the truth about the Earhart case. The rest, 99.9 percent, are biographies, novels, children’s books (the biggest sellers) and assorted fantasies — all except the good biographies that avoid the disappearance only muddle the picture and further obscure the truth.

The indisputable fact that this phenomenon exists tells us something is very wrong with the media’s relationship to the Earhart story. For the most recent example of media propaganda and malfeasance, we need only turn to our trusted Fox News and its June 27 non-news piece, “Amelia Earhart signed document discovered in attic box.” Moreover, Fox News has never allowed my name or the title of Truth at Last to stand in the comments section of any of its Earhart stories, to my knowledge.

As I wrote at the top of this post, Fred Goerner was the only newsman to ever publicly advocate for the Saipan-Marshall Islands truth in the Earhart disappearance. When you consider the few important books written about the so-called “Earhart mystery,” consider also the authors of these works. Obscure non-journalists such as Thomas E. Devine, Vincent V. Loomis, Oliver Knaggs, Joe Davidson and T.C. “Buddy” Brennan produced the important tomes about the Earhart matter. Paul Briand Jr., who authored the seminal work in the genre, Daughter of the Sky, in 1960, was an English professor at the Air Force Academy. Bill Prymak, an engineer by trade, was not an author, but his assemblage of Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters is as important as any but a few of the books, though the newsletters are unavailable to the public.

Why hasn’t any newsperson, author or journalist except Fred Goerner ever investigated the Earhart story? The question is rhetorical, of course, as the few who read this blog know, but its answer reveals the real problem.

Fred Goerner’s “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart” Part III

Today we move along to Part III of Fred Goerner’s January 1964 Argosy magazine opus, “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart.” When we left Part II, Goerner and missionary priest Father Sylvan Conover were trying to locate the gravesite of “two white people, a man and a woman, who had come [from the sky] before the war” that an otherwise unidentified Okinawan woman had shown to Thomas E. Devine in August 1945, and which Devine later wrote about extensively in his 1987 classic, Eyewitness: The Amelia Earhart Incident.

We continue with Part III of “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart”:

Father Sylvan and I matched the photograph to the terrain as best we could, and one of the natives showed us where a small dirt train had run past the southern boundary of the cemetery. Pacing off “thirty to forty feet to the left,” we arrived in a grove of trees, and with a crew of eight Carolinian natives, excavation began. We went to a depth of six feet among the trees, and then moved slowly to the west. About one o’clock, the afternoon of September twenty-first, Commander Bridwell, who had been watching the proceedings, let out a shout and brushed the natives back from a newly opened area.

Dozens of pieces of skull and many teeth were visible at both ends of a shallow grave not more than two feet in depth. Large teeth were found at one end, smaller ones at the other – indication that at least two individuals, perhaps a man and a woman, had been buried head to foot. As quickly as Bridwell had moved, several shovelfuls had been thrown aside, so, for the next four days, we sifted every bit of earth for a dozen feet around. Seven pounds of bones and thirty-seven teeth were recovered. The island’s doctors inspected the remains, and generally agreed that the grave had been occupied by a man and a woman. The dentists felt there was a strong possibility that the people had been Caucasians, as some of the teeth appeared to contain zinc-oxide fillings; the Japanese had never used that material.

Cutline from The Search for Amelia Earhart: “Father Sylvan Conover at grave site outside Liyang cemetery where remains were found in September 1961. The cross and stones were placed here by natives after the site had been excavated. Author’s Photo. (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

The afternoon the excavation was completed, we carefully wrapped the remains in cotton, and Father Sylvan placed the package in the church vault.

That night came the strangest experience of my life. I was staying in what was laughingly referred to as the “Presidential Suite.” It was nothing more than a Quonset hut, about twenty-five yards above the commander’s quarters. I don’t know what awakened me. It was about two o’clock in the morning and it was raining quite hard outside. As I sat bolt-upright on the cot, there was a flash of lightning, and I saw a man in the room by the door. I jumped from the cot and yelled at him, “What do you want?”

As he turned, I saw he had a machete in his hand. He stared at me for a second, then ran out through the front of the hut, banging the screen door behind him. I pursued him to the door, and in the glare of the running light on the front of the hut, I got a good look at him as he raced across the asphalt road and plunged into the jungle. He was a native – a man I was to hear a lot more from later.

As I tried to figure out what had happened, I was shaking so badly I could hardly light a cigarette.

“Were you really awake? Did you really see the man, or did you dream it?” I questioned myself. Wet sandal marks around the room leading from the door answered my question.

“What did he want?” was the next logical challenge. Certainly not my life. If he had wanted, he could have killed me as I lay on the cot. Expensive motion picture and still cameras and tape-recording equipment rested on the cot next to me. Several hundred dollars in cash was exposed on top of the bureau next to my passport. Nothing had been taken. Nothing had been disturbed. Nearly a year was to pass before the realization came as to what my visitor sought: The package of human remains I had given to Father Sylvan for safe-keeping.

The next day, I asked Bridwell for permission to take the package to an anthropologist in the States for study. He didn’t want the responsibility, and cabled Washington for clearance.

That night, as we waited for Washington’s answer, I received a mysterious summons by phone from a man named Schmitz. I was to be admitted to the NTTU area for the purpose of addressing their personnel on the subject of Amelia Earhart. A civilian in a handsome new car picked me up at my Quonset, drove me by circuitous route through the jungle, up a hill and deposited me in front of a night club! I mean a night club – complete with canopy leading from the road, dance floor, bar and stainless steel kitchen.

From Search: “Interior of NTTU Club where author addressed CIA training staff in Saipan, 1962.” Author’s Photo. (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

Mr. Schmitz (I never learned his full name) met me at the door and escorted me to the bandstand and waiting microphone. For the better part of an hour, I told an audience of several hundred, including many wives, of the investigation. Afterward, the applause was warm and prolonged, and many came forward to ask questions or contribute bits of information that had been heard from the natives. Mr. Schmitz and I had a drink at the bar and chatted for a while and then I was driven by the same circuitous route back to my “Presidential Suite.”

Just before I left the island, Bridwell began to cooperate. The invitation to NTTU had worked wonders. He readily admitted, “An ONI [Office of Naval Intelligence] man [Special Agent Joseph M. Patton] has been here checking on what you turned up last year. Most of the testimony couldn’t be shaken. A white man and woman were undoubtedly brought to Saipan before the war.”

The commander went on to expound his own theory: “I don’t believe Earhart and Noonan flew their plane in here. I think you’ll find that they went down near Ailinglapalap, Majuro and Jaluit Atolls in the Marshalls. The Japanese brought them to Saipan. A supply ship was used to take them to Yap in the western Carolines, and a Japanese naval seaplane flew them to Saipan. That’s why some of your witnesses said they came from the sky.”

“What have you got that’s tangible to prove that?” I naturally wanted to know.

“I think you’ll find all the proof you need,” replied Bridwell, “contained in the radio logs of four U.S. logistic vessels which were supplying the Far East Fleet in 1937. Remember these names: The [USS] Gold Star, [USS] Blackhawk, [USS] Chaumont and [USS] Henderson. I believe they intercepted certain coded Japanese messages that you’ll find fascinating reading.” (Editor’s note: Goerner reported nothing more about these four U.S. Navy ships in Search, or anywhere else, to my knowledge.)

Returning to San Francisco October 1, 1961, I was still without the last key to the Earhart puzzle, and without quite a few keys to NTTU. A few days later, a strange call came to me at KCBS from a Mr. Frederick Winter of the Central Intelligence Agency.

“I’d like to visit with you regarding a matter of national security,” he said.

“Of course,” I replied. “Come on up to our studios in the Sheraton-Palace.”

“Thanks, but I’d rather not,” rejoined Mr. Winter. “I’ll meet you in the lobby.”

From the back cover of The Search for Amelia Earhart: “Fred Goerner is a CBS radio broadcaster in San Francisco. A former college professor and World War II Navy Seabee veteran, he has been with station KCBS for seven years and has a popular afternoon program heard by tens of thousands of Californians. In 1962, he was honored with the Sigma Delta Chi National Journalistic Fraternity Distinguished Service Award for the best radio reporting in America. Born in Pittsburgh, Mr. Goerner now lives in San Francisco.” (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

“How will I know you?” I asked.

“Don’t worry about that,” assured Mr. Winter. “I’ll recognize you.”

Mr. Winter located me without any trouble, and suggested that we drop into the coffee shop for a bite of something. As long as I live, I’ll never forget that conversation. Mr. Winter had a dish of strawberry ice cream, and I had a cup of coffee. We talked, there in the coffee shop, about one of the best-kept, most important U.S. Intelligence secrets since the end of World War II.

“Mr. Schmitz has alerted us,” began Winter, “that you have turned up a good deal of information regarding NTTU and Saipan. Washington has asked me to talk to you about the matter and to ask you to withhold this information from publication or broadcast until you are given a release. We know you to be a good American, and we hope you will comply.”

I agreed. Mr. Winter didn’t know that I had already made that decision.

The conversation lasted a little more than a half-hour, and then, with a hearty handshake we parted. I have not seen Mr. Winter since, although we’ve had one brief telephone conversation.

Was Mr. Winter really from the CIA? I wondered for a while myself. I hadn’t asked for identification, but I wouldn’t have known the proper card anyway. For protection, I wrote a note to John McCone, head of the CIA in Washington.

“We’re happy to inform you that Mr. Frederick Winter is the man he represents himself to be,” was the answer.

Lengthy conversations began with the Navy Department about whether an expert was to study the remains. The Navy stipulated a number of things that must be done before the package could be released; among them was written permission from the next of kin. There was no definite indication the remains were those of Earhart and Noonan, but the Navy wanted as much time as possible and was taking no chances.

Dr. Frank Stanton of CBS flew out from New York, and the entire situation was discussed. We all strongly felt that nothing should be broadcast or printed before a positive identification of the remains could be made. If identification was not possible, the package could be returned to Saipan without publicity. The primary consideration should be for next of kin.

I visited Amelia Earhart’s sister, Mrs. Albert Morrissey, in West Medford, Massachusetts, and presented the facts of the total investigation.

She thanked me for my efforts and granted permission on behalf of Amelia’s mother, who has since passed away [Oct. 29, 1962] at ninety-five years of age.

A week later, I met Mrs. Bea Noonan Ireland, the remarried widow of Fred Noonan, now living in Santa Barbara, California. She also gave her consent to do whatever was necessary to write an end to the mystery.

Original caption from Search: “At nationally broadcast KCBS news conference in San Francisco, November 1961, the author (at table, right) is questioned by newsmen about package of remains being flown in from Saipan. Don Mozley, KCBS Director of News, sits at table with Goerner. Author’s Photo. (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

Dr. Theodore McCown, University of California anthropologist, was then asked to do the study should the Navy release the remains. He agreed.

It was another month before Navy permission was granted, and unfortunately, we had to learn of it from a wire service. A previous arrangement had been made for Father Sylvan to take the package from Saipan to Guam, address it to Dr. McCown, and ship it by commercial airliner to its destination.

Navy permission went direct to Saipan, and Father Sylvan carried through with his part. Someone on Guam, however, perhaps a customs official, leaked the story to a representative of Associated Press, and it was on every broadcast and every paper in the country before we could do anything to stop it.

There was nothing to do but admit we had been pursuing the investigation.

Dr. McCown’s study took a week, and his findings were disappointing in the extreme. Instead of two people, we had found three, perhaps four. At least one man and one woman were represented by the remains, but the strongest indications were that these people had been indigenous to the Saipan area. The “zinc-oxide” fillings that had excited the dentists on Saipan turned out to be calcified dentine. X-rays showed there were no metallic fillings present. “The hypothesis that the remains represented those of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan,” wrote Dr. McCown, “therefore is not supported.”

Privately, however, McCown told us, “Don’t be discouraged. You may have missed the actual grave site by six or sixty feet. That’s the way it is with archeology. In all my experience, I have never known a story with as much testimony supporting it as this one, not to have some basis in truth.”

Thomas Devine was also disappointed. His disappointment turned to frustration when he saw a complete set of photographs I had taken of our excavation and the surrounding area.

You were on the wrong end of the cemetery,” he wrote. “I’m sure now that the site was outside the northern perimeter, not the southern. There was a small dirt road that ran by the north side, too. Did you try to match that one photo against the mountain from the north side?”

From Search: “Dr. Theodore McCown, University of California (Berkeley) anthropologist, announces at December 1961 news conference his finding that the remains were not those of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan. Center background is Jules Dundes, CBS Vice-President and General Manager of KCBS Radio, San Francisco. Author’s Photo.” (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

I admitted I hadn’t because the jungle had grown too high in that area.

Nineteen sixty-one’s news reached the front page of nearly every newspaper in the nation, and a number of persons were motivated to come forward with bits of information. (Editor’s note: Here Goerner exaggerates the media coverage his investigation received, as I’ve found no evidence that any major newspapers published a single story about Goerner’s four Earhart investigations on Saipan in the early 1960s. Many smaller newspapers around the country did run stories produced by the San Mateo Times, Associated Press and United Press International, as shown in this clip from the Desert Sun, a local daily newspaper serving Palm Springs and the surrounding Coachella Valley in Southern California. But I’ve searched in vain for any traces of Goerner’s early 1960s Saipan investigations in papers such as the New York Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune or Los Angeles Times, to name just a few of the prominent newspapers that blacked out news of the search for Amelia Earhart on Saipan.)

Eugene Bogan, now a Washington, D.C. attorney, had been the senior Navy military government officer at Majuro Atoll in the Marshalls after the January 1944 invasion. Bogan claimed that several natives told him that two white flyers, one of them a woman, had landed their airplane near Ailinglapalap, close to Majuro, in 1937, and were taken away on a Japanese ship bound for Saipan. “The name of one of the natives is Elieu [Jibambam],” Bogan said. “Elieu was my most trusted native assistant.”

Charles Toole, of Bethesda, Maryland, now an expert in the Manpower Division of the Under Secretary of the Navy, had been an LCT (landing craft tank) Commander, plying between the same islands in 1944. “Bogan is absolutely right,” said Toole. “I came across the same information myself.”

Why didn’t Bogan and Toole file an official report on their findings?

“We were discouraged by the senior officer responsible for that over-all area in the Marshalls,” they replied. “The reason he gave was that there wasn’t any sense in raising false hopes at home that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan might still be alive.” (End of Part III.)

Fred Goerner’s “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart,” Part II

Today rejoin Fred Goerner for Part II of his January 1964 Argosy magazine opus, “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart.” When we left Part I, Goerner was learning a few details about the mysterious Naval Technical Training Unit (NTTU), the CIA spy school located in the northern end of Saipan that he was told to judiciously avoid by Commander Paul Bridwell, the top Navy administrator on the island, who knew far more about the Earhart disappearance than he ever let on to Goerner or anyone else in the media.

Without further delay, here is Part II of “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart”:

I started to draw the conclusion that the Navy was giving Nationalist Chinese some special training. The guess was inadequate, although I felt my suspicions were confirmed by an inadvertent slip at the officer’s club. Bridwell had a dinner party in my honor, and one officer’s wife, after a half-dozen cocktails, gushed, “Yes, you have to know of a lot of languages on Saipan: Chamorro, Spanish, German, Japanese. And now we’re even speaking Chinese.”

There was a hush at the table as if someone had used an especially pungent four-letter word, and then the conversation picked up at double time.

One day, Father Sylvan took me up Mount Tapochau, a little over 1,500 feet, the highest point on Saipan. From there, one can see the whole island, but not down into the jungle. I shot about a hundred feet of motion-picture film and a few stills, and then we headed back to the village.

Original photo and cutline from The Search for Amelia Earhart: “View from Mount Tapochau of northern end of Saipan Island in 1961. The jungle hides eleven installations of Naval Technical Training Units, where agents were trained. Author’s Photo.” (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

Commander Bridwell was waiting. “Understand you’ve been up Tapochau with your cameras?” he said.

“Right. Nice climb and view. Couldn’t see into your restricted areas, though.”

“I wasn’t really worried about that.” He smiled. “But we’d like it very much if you dropped your film off with the PIO officers at Guam for a look-see.”

Before I left Saipan in 1960, I let one question get the better of me: Did Earhart and Noonan fly their plane to Saipan? It seemed incredible. Saipan lies about 1,500 miles due north of their final take-off point, Lae, New Guinea. Saipan, with Howland Island as an intended destination, would have represented a navigational error of ninety to a hundred degrees. Yet there was that possibility. The question enlarged to: If they did fly here, could any part of that plane still remain on the bottom of Tanapag?

Monsignor Calvo brought me Gregorio Magofna and Antonio Taitano, who had been shelling and fishing in the harbor for many years. After viewing a photograph of Amelia’s Lockheed Electra, Greg and Toni agreed that they knew of the wreckage of a “two-motor” plane. About three-quarters of a mile from what was once the ramps of the Japanese seaplane base, we went down in twenty-five to thirty feet of water.

The bottom of Tanapag Harbor is like another world. Every conceivable type of wreckage is littered as far as a face mask will let you see. Landing craft, jeeps, large-caliber shells, what’s left of a Japanese destroyer, the Japanese supply ship, Kieyo Maru, in deeper water beyond the reef, a huge submarine – all covered with slime and of coral.

The “two-motor” plane proved to be a huge, twisted mass of junk. From this incoherent form, we hauled several hundred pounds of vile-smelling wreckage to the surface. Later, I knocked a chunk of coral as big as a man’s head from one piece of equipment, and found the first sign of aircraft-parts wired together. In the early days, before the advent of shakeproof nuts, this was standard procedure.

It was not until [Rear] Admiral [Waldemar F.A.] Wendt’s technicians at Guam announced that the equipment possibly could have come from the type of aircraft Amelia had flown, that I began to have some hope for its identification. My motion-picture and still films were checked, and I headed back home. (Editor’s note: After promotion to rear admiral, Wendt assumed command on Jan. 17, 1960 of U.S. Naval Forces Marianas, with additional duty as CINCPAC representative, Marianas-Bonins, as Deputy High Commissioner of the Marianas District of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, and as Deputy Military Governor of the Bonin-Volcano Islands; with headquarters in Guam.)

From The Search for Amelia Earhart: “Examining the generator at a news conference in San Francisco in July 1960 are, left to right: Moe Raiser, Associated Press Reporter, Paul Mantz, and the author. World Wide Photo. (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

In San Francisco, July 1, 1960, the tape-recorded testimony of Saipan’s natives made an impression on the press, but the wreckage created much more interest. Several numbers found on the interior of what was once a heavy-duty generator were sent to Bendix Aircraft in New Jersey. Several days later, Bendix, which had manufactured much of the electrical equipment carried on the Lockheed Electra, announced that the bearings had been produced by the Toyo Bearing Company of Osaka, Japan. The equipment was a Japanese copy of Bendix gear!

The Saipanese witnesses somehow became lost in the reverberations from the Bendix press release, and Earhart and Noonan were again assigned to limbo.

If detailed, the next part of the investigation would fill a book. It concerns the search by the Navy and Coast Guard, in 1937. I’ll sketch the high points in a very few words.

We obtained photostatic copies of the message log of the Itasca, Amelia’s Coast Guard homing vessel at Howland Island, and the search report of the U.S.S. Lexington, the carrier dispatched by the Navy to hunt for the missing flyers. What we found produced a mystery within a mystery. Immediately after the plane was thought lost, the Itasca had radioed to the San Francisco Division of the Coast Guard a group of messages purportedly to have come from the Earhart plane. Three days later, another group of messages, also supposed to have come from Amelia, was sent to San Francisco. From the first to the second group, the time and content of every message had been much altered.

How could such discrepancies occur?

The answers of two of the radio operators who were aboard the Itasca that morning in 1937 were a continuing contradiction. William Galten, of Brisbane, California, was radioman, third-class. He maintained that the first group was correct. Leo Bellarts, of Everett, Washington, was the chief radioman, charged with handling all the communications with the plane. He stipulated that the second group was accurate.

Coast Guard Chief Radioman Leo Bellarts led the Itasca radio team during the last flight of Amelia Earhart. According to Leo’s son, David Bellarts, this photo was taken on July 2, 1937. Whether it was shot before or after the Earhart plane’s expected arrival is unknown. (Photo courtesy David Bellarts.)

I went to see Galten, and when faced with the photostats and Bellarts’ statement, he admitted, “I may have been mistaken. We were under great pressure.” (Editor’s note: Goerner’s description of “two groups” of alleged messages from the Earhart plane, with one being accurate, the other inaccurate, is itself inaccurate, as well as confusing. For an accurate discussion on this topic, see “Chapter III: The Search and the Radio Signals” in Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last.)

You may have already guessed this: The Lexington’s planes flew over 151,000 square miles of open ocean, an area determined only by the first group of messages, not one of which was correct as to time or content.

Why didn’t the Navy double check with the Itasca, or why weren’t the corrected group of messages relayed from San Francisco to the Lexington? There are only two possible answers: A completely unexplainable lack of communications between the Navy and the Coast Guard – or design. When you know that the Navy spent nearly $4,000,000 on the search, it becomes utterly incredible. Heads have certainly rolled for less.

The statement I have just made was contained in a monograph I sent to the Navy Department in 1962. Some five weeks later, I received a call from a chief at the Coast Guard office in San Francisco, advising me to check the next day’s edition of the Navy Times for further information on the Earhart matter. The next day, the Coast Guard released a report that had been kept in a classified file for twenty-five years. It was the report of Commander Warner K. Thompson, who had been the commanding officer of the Itasca in 1937. It revealed that the Coast Guard had known next to nothing about the plans for the final flight; that the Navy appeared to be handling the whole show; that the Navy had brought special direction-finding equipment aboard the Itasca; that on the morning of the disappearance, a number of secret messages signed with the code name “Vacuum” were received aboard Itasca addressed to one Richard Black, who ostensibly was a Department of Interior employee. The Coast Guard felt it had been used as a front and could not be blamed for anything when it have been given so little information.

The overtones of “intelligence” become quite audible, but I’m ahead of the story.

This story, which announced Thomas E. Devine’s Saipan gravesite claim, appeared in the San Mateo Times on July 16, 1960. Devine returned to Saipan in 1963 and located the gravesite shown to him by the Okinawan woman in August 1945, but did not share his find with Fred Goerner. Instead Devine planned to return to Saipan by himself, but he never again got the opportunity.

Early in 1961, I felt we had more than enough to warrant another trip to Saipan. In addition to further questioning of the natives and raising more of the wreckage from Tanapag Harbor to establish its identity, I wanted to follow through on information given to us by Thomas E. Devine of West Haven, Connecticut. Devine had been a member of an Army postal unit on Saipan in 1945, and claimed that a native woman had shown him the grave of “two white people, a man and a woman, who had come before the war.” Devine said he had not connected the incident with Earhart and Noonan until he read of our investigation. For evidence, he produced pictures of the native woman and an area near a tiny graveyard where the woman had lived. He also provided a fairly detailed description of the unmarked grave’s location outside a small cemetery.

Navy permission to go to Saipan was really tough to come by this time. The first application was filed in April 1961, and for several months, there was no answer.

In June, Jules Dundes, CBS Vice President in San Francisco, called Admiral [Daniel F. Jr.] Smith’s office in Washington, and finally got Captain [R.W.] Alexander, then the Navy’s Deputy Chief of Information, on the phone. Alexander flatly stated that permission to return to Saipan was denied.

Not liking the tenor of that conversation, Dundes called CBS Vice President Ted Koop, in Washington, who promptly went to work with Arthur Sylvester, Assistant Secretary of Defense. Early in September, I departed for the now familiar Marianas – with the necessary clearance.

I went back with a bit more information about our friend, NTTU, too. Control of Saipan had been transferred from Department of Interior to the Navy by Presidential order in 1952. Shortly thereafter a contract amounting to nearly $30,000,000 was let to an amalgamation of three companies, Brown-Pacific-Maxon, for the construction of certain facilities on the north and east side of the island, the concrete foundations of which went down ten to twenty-five feet.

At Guam, I told Admiral Wendt what I thought might be going on. Then, at Saipan, I met once again with my old friend Commander Bridwell, who quickly reiterated that I was to stay away from the north end and the east side of the island.

Cmdr. Paul W. Bridwell, chief of the U.S. Naval Administration Unit on Saipan, and Jose Pangelinan, who told Fred Goerner he saw the fliers but not together, that the man had been held at the military police stockade and the woman kept at the hotel in Garapan. Pangelinan said the pair had been buried together in an unmarked grave outside the cemetery south of Garapan. The Japanese had said the two were fliers and spies. (Photo by Fred Goerner, courtesy Lance Goerner.)

“Look, Paul,” I replied. “I’m not after NTTU. Quit muddying the water for me on the Earhart story. Let us get the final answer and you’ll have me off your back. It’s not my business if you’re training Nationalist Chinese or operating ballistic missile sites; that’s a security matter.”

“We’re glad you feel that way,” returned Paul, but if you do come up with the final answer to Earhart, a dozen newsmen will be knocking on our door.”

“Don’t you believe it, I retorted. “No one is going to send a photographer six thousand miles to duplicate something we already have. Just cooperate with me.”

Bridwell finally did cooperate – the day before I left Saipan for the second time, and only after I had received an invitation to enter the super-secret NTTU area. Bridwell believes strongly that Amelia and Fred were brought to Saipan in 1937 and their lives ended six months to a year later, but at that time, he was obliged to block the investigation in any way he could. He and the rest of the Naval Administration Unit were fronting for the Central Intelligence Agency.

I know now that word was passed to natives working for the Navy or NTTU that it would be best to reply in the negative to questions asked about any Americans being on the island before the war. Bridwell even attempted to get witnesses to change their testimony. In one case, he was successful. Brother Gregorio, now with the Church at Yap, had been on Saipan in 1937. Father Sylvan had seen him during the year I had been gone. Brother Gregorio said that he had heard from several people that a white man and woman, reportedly flyers, had been brought to Saipan. He had not seen them himself because the Japanese had restricted him to the church, but he gave the names of the two men who had told him. Commander Bridwell got to them first. The pair had jobs with the Navy and refused to talk. I hold no grudge. The Navy did what it felt necessary to protect the CIA.

During the ’61 stay, Magofna and Taitano took me back down to the wreckage off the old seaplane ramps, and an afternoon of diving produced conclusive evidence that the “two-motor” plane was Japanese. A corroded plate from a radio-direction finder unmistakably bore Japanese markings.

Father Sylvan and I then went to work on Thomas Devine’s information. The small graveyard was easy to locate. One of Devine’s photos showed a cross in the graveyard; another pictured an angel with upraised arms surrounded by crosses and tombstones. The only change was the jungle. It had grown up forty or more feet over the cemetery. Devine had also sent a picture of the woman who had shown him the grave site. Father Sylvan showed the print to a native who works for the mission, and the old man brightened.

Okinawan woman who showed Thomas E. Devine the location that Devine believed was the Earhart-Noonan gravesite on Saipan in 1945. (Photo by Heywood Hunter. Courtesy of Thomas E. Devine.)

“Okinawa woman,” he said. “Sent back Okinawa after war.”

Father Sylvan acknowledged that many Okinawans and Koreans had been brought to Saipan by the Japanese before the war to build airfields and harbor installations. All who hadn’t married Chamorros or Carolinians were repatriated.

Devine had indicated that the grave site was outside the cemetery. Another of his photographs, taken from a narrow dirt road with the island’s mountain range in the background, was supposed to have the most significance. “The grave,” Devine had written, “is located thirty to forty feet to the left of this road.” (End of Part II.)

First of four-part 1964 Argosy magazine special: Fred Goerner pledges “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart”

Today we remain in Fred Goerner’s mid-1960s heydays, a few years before the The Search for Amelia Earhart became a bestseller in 1966 and just as Goerner had departed for his fourth visit to Saipan. From the January 1964 issue of the now-defunct Argosy (“For Men”) magazine, we present “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart,” which, to my knowledge, is the first of just two nationally published accounts of Fred Goerner’s early 1960s investigations on Saipan, this one covering his first three trips, from 1960 to 1962. A few years later, the September 1966 issue of True magazine published a long preview of the soon-to-be-published Search. (Boldface emphasis mine throughout.)

This photo, taken sometime after Amelia Earhart’s June 1928 arrival in Burry Port, Wales, after becoming the first woman to fly the Atlantic, with Wilmer “Bill” Stutz and Louis E. “Slim Gordon” in the tri-motored Fokker monoplane Friendship, set the tone for Fred Goerner’s first-person narrative, “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart.” Goerner’s lengthy piece highlighted Argosy magazine’s January 1964 issue, but it was not the cover story. (Photo by UPI.)

I found this story only recently; I think, but am not entirely certain, that it’s Goerner’s earliest published national account of his Earhart investigations. The story reflects his passion for the truth and determination to succeed against the increasingly trenchant stonewalling policies of the U.S. government he was beginning to experience, as the feds circled their wagons around another sacred cow. At this stage of his research, Goerner had yet to fully understand the true nature of the forces arrayed against him. Once again, just as in my last post, you are invited to compare the below story with the mendacious, ridiculous fare about the Earhart “mystery” we’re force-fed today, as the U.S. government-media Earhart disinformation machine continues to click on all cylinders, and more people than ever are ignorant about the facts.

As I always try to do with original material, I’m reproducing this article as it appeared in Argosy as closely as possible, using the same photos and cutlines and editing only for mistakes that would distract. Because of the its length, I’ll present “I’ll Find Amelia Earhart” in four segments. Forthwith is Part I, as we return to January 1964.

“I’LL FIND AMELIA EARHART!” Continued from page 25

before the war and were taken to Saipan by the Japanese.”

• A United States Naval Manpower Division Expert, who says, “The fliers, according to the Marshallese natives, were taken away on a Japanese ship – presumably to Saipan.”

• One of the most respected natives in the Marshall Islands, who backs up the stories of both: “The Japanese were amazed that one of the flyers was a woman.”

• A former U.S. Naval Commandant of Saipan, who states: “The testimony of the Saipanese people cannot be refuted. An ONI man was there, and regardless of what they tell you in Washington, the story couldn’t be shaken. A white man and woman were undoubtedly brought to Saipan before the war. Quite probably they were Earhart and Noonan. I don’t believe they flew their plane in here. They were brought by the Japanese from the Marshalls. I think you’ll find the radio logs of four U.S. logistics vessels will prove that.”

• A series of strange discrepancies appearing in the official logs of the Coast Guard Cutter Itasca, Earhart’s homing vessel at Howland Island in 1937, and the U.S.S. Lexington, the Navy carrier dispatched to search for her and Fred.

• Literally hundreds of bits of information, none of which have been satisfactorily answered by official sources, that point directly to the Saipan conclusion.

• A strong feeling that Earhart and Noonan may be the key that will make public the truth behind one of the most incredible and least-known periods in United States Military Intelligence history – the twenty years that led to Pearl Harbor.

The evidence is so great that, as you read this, I will once more be on Saipan. This is the fourth expedition in as many years, and this trip may well provide the final answer we have so diligently sought.

For me, it began in April 1960, with Josephine Blanco Akiyama of San Mateo, California. The San Mateo Times had printed a series of articles in which Mrs. Akiyama was quoted as having seen “two white people, a man and a woman, flyers, on Saipan in Japanese custody in 1937.”

From Fred Goerner’s January 1964 Argosy story, here’s the original caption: “Workers sift earth at Saipan grave believed to have been burial site of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan. Teeth and pieces of skulls were found, but identification was inconclusive.” (Photo by Fred Goerner.)

More than a little skeptical, I called her to ask why she had been late in making the story public.

“I told about it a long time ago,” was her reply. “I told a Navy dentist I worked for on Saipan in nineteen forty-five.”

The Navy dentist turned out to be Casimir Sheft, now in civilian practice in Passaic, New Jersey. Sheft didn’t know that Mrs. Akiyama had come to the United States, but he did back up her story.

“I tried to do something about it,” said Sheft, “but the naval officers I discussed it with didn’t seem interested in starting an investigation. I felt sure Washington knew about it anyway, so, when I returned to the States after the war, I forgot about it.”

The possibility of corroborative testimony seemed to me to be sufficient to warrant an expedition to Saipan. There was a ring of truth to the stories of both Mrs. Akiyama and Dr. Sheft, and it seemed logical to assume that if Josephine Akiyama, as a young girl, had learned about “two white flyers,” there must be others still alive on that island who knew something.

Permission to visit Saipan wasn’t easy to obtain. At first, it was denied, then, after various appeals, the Navy Department relented. Early in June 1960, I left for the Marianas. I paused at Guam for clearance and Navy transportation to Saipan, and the aura of secrecy was deepened when naval officials told me that, on Saipan, I was to behave myself and if I were a member of the military.

From the air, Saipan, a twelve-by-five-mile dot, appears to be a tropical paradise. On the ground, the impression is entirely different. Scene of some of the most brutal fighting of World War II, Saipan still shows the scars. The rusting hulks of tanks and landing craft are scattered on her reefs, and the shattered superstructures of sunken Japanese ships protrude above the surface of her harbors. The jungles have covered the craters and foxholes, but in a day’s time, enough live ammunition to start a small revolution can still be collected.

In the 1944 invasion, the United States forces suffered more than 15,000 casualties. The cost to Japan and the natives was even more dear. Twenty-nine [thousand] of 30,000 Japanese troops and an estimated half the native population were killed.

The cloak-and-dagger atmosphere was not dispelled at Saipan. Immediately after landing, Commander Paul Bridwell, head of the Naval Administration Unit, whisked me to his quarters overlooking Tanapag Harbor, and spelled out some basic rules for my behavior while on the island. I was not to go further north on Saipan than the administration area, and under no circumstances, was I to go over to the east side of the island.

“What’s this all about, Commander?” I asked. “What does this have to do with the Earhart investigation?”

“Not a thing,” was the answer. “Are you sure you’re here about Amelia Earhart?”

“Of course I am,” I answered. “What else? Why all the secrecy? Why can’t I visit other parts of the island?”

“A lot of questions,” replied Bridwell, “but I’m afraid I can’t give you any answers. Just confine yourself to the area I’ve indicated and we’ll get along fine.”

Also from Fred Goerner’s 1964 Argosy story, the original cutline read: “This is jail where witnesses say ‘American woman flyer’ was held by Japanese on Saipan before the war. Reports generally agree that she died or was executed by her captors.” (Photo by Fred Goerner.)

You know about the bull and the red flag? Well, that’s how such a conversation affects a newsman. But I decided I had come on the Earhart story, and on the Earhart story I would work.

It’s an understatement to say that it’s difficult to conduct an investigation when half the territory is denied you, but Bridwell was very anxious to be of help. He gave me the names of some ten natives “who should know if Earhart and Noonan were on the island.” He personally led me to the natives and, to a man, they knew nothing. They were not only vague about everything before the war, I began to get the feeling I was listening to a phonograph record.

It was then I enlisted the aid of Monsignor Oscar Calvo, Father Arnold Bendowske and Father Sylvan Conover of the Catholic Church Mission at Chalan Kanoa. Nearly all of the 8,000 Chamorros and Carolinian natives who inhabit Saipan today embrace Catholicism. Monsignor Calvo, a native of Guam, Father Sylvan of Brooklyn, New York, and Father Arnold of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, had not been on the island before the war. A Spanish Jesuit priest and a lay brother had operated the mission under the Japanese. Father Tardio returned to Saipan after the war, where he died. Brother Gregorio is stationed at the church mission at Yap.

Monsignor Calvo told me that the natives I had been led to by Commander Bridwell all worked for the Navy or a mysterious entity known only as NTTU, that inhabited the parts of Saipan I was not to visit, under penalty of no one knew what. Monsignor and the two priests had heard vague rumors about some white people held on the island before the war, but had not done any probing. They were glad, however, to help if they could.

I first laid some ground rules for the questioning: We would not ask people if they remembered the two white flyers captured by the Japanese before the war. We would first talk about recent years, then the period of the war, and finally pre-war Saipan. At a likely moment, Monsignor Calvo would ask, “Did you ever see or know of any white people on the island before the war?” If the reply was no, the questioning would be dropped. If the answer was affirmative, we would try to determine if a firm identification and a definite year could be established.

Here, I am going to lump together all the testimony gathered during the three trips, 1960, 1961 and 1962. In questioning nearly a thousand Saipanese, Monsignor Calvo, the fathers and I turned up twenty-three witnesses, and this is their story:

Two white flyers, a man and a woman, arrived at Tanapag Harbor in 1937. The woman had very closely cut hair, and at first, appeared to be a man. They were brought ashore in a Japanese launch and taken by command car into the city of Garapan to military headquarters. (Garapan was completely destroyed during the 1944 invasion.) After a period of time in the building, the pair was separated. The man, who had some kind of a bandage around his head, was taken to the military police barracks stockade at Punta Muchot, while the woman was placed in a cell at Garapan Prison. Shortly thereafter, probably after a few hours, the woman was taken from the prison back into Garapan to a hotel which served as a detention center for certain political prisoners.

The woman was kept at the hotel for a period of from six to eight months. Allowed a brief period of exercise each day in the yard, she was constantly kept under guard. After the aforementioned six to eight months, the woman died of dysentery. She was buried a day or so later, just outside a native cemetery near Garapan, in an unmarked grave. The man who had come to the island with her was taken with the woman’s body to the graveside, beheaded and buried with her. The Japanese said several times that the two had been American flyers spying on Japan.

This photo is taken not from the Argosy story, but from The Search for Amelia Earhart, but it fits well here. The original cutline reads: “On Saipan during the author’s 1960 expedition, left to right: native witnesses William Guerrero Reyes and Joseppa Reyes Sablan, Fred Goerner, Monsignor Oscar Calvo, and Rev. Father Arnold Bendowske of Saipan Catholic mission. Author’s Photo.” (Courtesy Lance Goerner.)

Who are these witnesses? Men who worked for the Japanese at the Tanapag naval base; men and women who lived in Garapan near the Japanese military police headquarters; a native laundress who served the Japanese officers, and many times washed “the white lady’s clothes. In the beginning, she wore man’s clothes,” says this witness; a woman whose father supplied the black cloth in which the white woman was buried; a dentist who worked on the Japanese officers and heard what they said about the two American flyers; a woman who worked at the Japanese crematorium near the small cemetery and saw the man being taken to his execution, along with the woman who was already dead; a man who was imprisoned at Garapan prison by the Japanese from 1936 to 1944, and who saw the woman the Japanese called “flyer-spy.”

“Are you sure they are telling the truth?” I asked Monsignor Calvo.

“I’m certain,” he replied. “In the first place, these simple people couldn’t concoct a story like this. They come from different parts of the island. There would be immediate discrepancies. I’m a native myself, and I know when a lie is being told. Finally, they have no reason for telling a lie. Nothing has been paid to them. What can they gain?”

Another question was logical: “Why haven’t these people come forward before?”

“Why should they?” Monsignor questioned back. “If you knew these people’s history, you wouldn’t wonder. They have never had self-determination. The Spanish conquered them first, then the Germans. The Japanese forced the Germans out in nineteen-fourteen, and used the island for their own purposes until the American invasion. The Japanese had so convinced the Saipanese that your forces would torture them if they were captured, that whole families committed suicide by throwing themselves off Marpi Cliff. Now you have a United Nations trust over Saipan, and they aren’t convinced you are going to stay. Two white people on Saipan before the war are of no interest to them. Why should they have told something that might have reflected badly on them?”

As we gathered testimony about the two flyers resembling Earhart and Noonan, a few tidbits about NTTU also came to light. NTTU, I learned stood for Naval Technical Training Unit. High wire fences surrounded the restricted area. Aircraft were landing at Kagman Field on the east side of the island in the dead of night. Large buses with shades drawn were regularly seen shuttling between the airfield and the jungle. There were a large number of American and civilian and military personnel within the restricted area, and they were seldom seen on the south end of the island. One native said he’d seen Chinese, presumably soldiers, moving through the jungle inside the restricted area. (End of Part I.)

KCBS 1966 release a rare treasure in Earhart saga

In late October of this year, Ms. Carla Henson, daughter of the late Everett Henson Jr., contacted me for the first time, completely out of the blue. You will recall Pvt. Henson, who, along with Pvt. Billy Burks, was ordered by Marine Capt. Tracy Griswold to excavate a gravesite several feet outside of the Liyang Cemetery on Saipan in late July or early August 1944. This incident is chronicled in detail on pages 233-253 in Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last.

When the pair had removed the skeletal remains of two individuals and deposited them in a large container that Henson later described as a “canister,” Henson asked Griswold what the impromptu grave-digging detail was all about. Griswold’s reply, “Have you heard of Amelia Earhart?” has echoed down though the decades and continues to reverberate among students of the Earhart disappearance.

On Nov. 22, Carla, 66, long ensconced as the “Agent of First Impressions” at ABC10 in Sacramento, Calif., sent me the below KCBS press release in its original July 25, 1966 format, created about a month before The Search for Amelia Earhart was published. Thanks to Carla, on this day after Christmas 2017, I’m privileged to present this rare treat you will see nowhere else.

Because the remaining four pages of the 1966 release do not reproduce well in this format, I’m typing them afresh while making every effort to duplicate the original in every way possible, including paragraph indents and page numbers. I’ve added the photos for obvious reasons. Compare the content of the below piece, as true today as it was then, with the ambiguous and confusing information typified by the Nov. 25 Pacific Daily News story, “Chamorro man shares Earhart theory that she was a prisoner on Saipan,” discussed in my last post, “Recent Earhart stories aim to confuse and deceive,” and you can see how much real progress has been made in the Earhart case by our esteemed media — mainstream or any other kind — during the past 61 years. Less than none is the pathetic truth.

-2-

San Francisco, July 25 . . . A KCBS Reporter who spent six years investigating one of aviation’s greatest mysteries charged today that famed aviatrix Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Frederick Noonan — who mysteriously disappeared during a Pacific Ocean flight 29 years ago this month — were in fact captured by the Japanese in the Marshall Islands and accused of spying for the United States. Transferred to Japan’s Pacific military headquarters, Saipan Island in the Marianas, Miss Earhart later died of dysentery, and Mr. Noonan was executed. They were buried in an unmarked grave near a native cemetery on Saipan. In 1944, representatives of the U.S. Government, after Saipan had been wrested from the Japanese during World War II, recovered the Earhart-Noonan remains in secret. The public was never informed. (Boldface emphasis mine throughout.)

These incredible conclusions to one of the 20th century’s greatest mysteries were revealed today by former U.S. Marines, and are supported by a six-year investigation into the 1937 disappearance of Amelia Earhart by KCBS Radio of San Francisco, The Napa California Register, The Scripps League of Newspapers and the Associated Press. The investigation, begun in 1960 by Fred Goerner of KCBS Radio and joined three years ago by the other media, entailed four expeditions to the Marianas and Marshall Islands, the questioning of literally hundreds of persons, and probes in the Far East and Washington, D.C. Goerner has just completed a book, “The Search For Amelia Earhart,” detailing the investigation, which will be published next month by Doubleday and Company and The Bodley Head Press Ltd. of London, England.

First word of the recovery of the remains of Earhart and Noonan came from Everett Henson, Jr., now an appraiser for the Federal Housing Administration in Sacramento, California. In 1944, Henson served as a Private with the U.S. 2nd Marine Division during the invasion of Saipan, a 12 x 5 mile island 115 miles north of Guam.

“One day,“ said Henson, “a Captain in Marine Intelligence took me and another Private to a small native graveyard. We searched around outside the graveyard until he found a grave that was marked only by some small white rocks. Then he had us open it up and take out the two people inside. I asked him what we were doing, and he said, ‘Did you ever hear of Amelia

In this undated photo from the mid-1960s, Fred Goerner holds forth from his perch at KCBS Radio, San Francisco, at the height of his fame as the author of The Search for Amelia Earhart. (Photo courtesy of Merla Zellerbach.)

-3-

Earhart?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ And he said, ‘Then that’s all I should have to say.’ He warned us not to say anything about it, but that was more than twenty years ago. I can’t see any harm in telling the truth now.”

Henson recalled that the other Marine Private’s name was Billy Burks. After a search of several months, Burks was located in Dallas, Texas. When questioned, he told a story almost identical to Henson’s, although the former Marines had not seen each other since the end of World War II.

Contacted in Washington, D.C., General Wallace M. Greene, Jr., currently commandant of the Marine Corps, states, “I do not quarrel with the theory that Amelia Earhart and Frederick Noonan went down in the Marshall Islands, but the Marine Corps does not take a position on the recovery of any remains on Saipan Island.”

Two other former U.S. Marines, Captain Victor Maghokian, USMC, Ret., of Las Vegas, Nevada, and W.B. Jackson of Pampa, Texas, have testified they learned in 1944 that Earhart and Noonan were held for a period of time by the Japanese in the Marshall Islands and that some of the personal effects of Miss Earhart were recovered and turned over to U.S. Intelligence. General Greene also declines to take a position for the Marine Corps in regard to the findings in the Marshalls. Additionally, three former U.S. Navy men, Eugene Bogan of Washington, D.C., Charles James Toole of Bethesda, Maryland and John Mahan of Berkeley, California, testify they learned that Earhart and Noonan were held for a period by the Japanese in the Marshalls.

With the help of Senator Thomas Kuchel of California and Ross P. Game, Editor of the Napa California REGISTER newspaper, access has been gained to classified files held by the U.S. Navy and State Departments. Both Departments have denied over the years that such files existed. Perusal of this data indicates a deep involvement on the part of the U.S. Government and President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the Earhart flight and the unavoidable conclusion that Amelia Earhart and Frederick Noonan were on a several-fold mission for the

-4-

This photo of Maria Hortense Clark and Pvt. Everett Henson Jr., at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, was taken on May 20, 1945, the day of their marriage. “He was done with the Pacific campaigns and stationed at the Presidio teaching ROTC,” Carla Henson, their daughter, wrote recently. “He and my mother met at the home of my godmother and her family, Frazier, half Scottish and half Chilean. They hosted Christmas dinner in Oakland (1944) for soldiers who couldn’t get home. They were married by May and needless to say, they really didn’t know each other very well, but that’s what they did during that war, right? Maria was a ballroom dancer and entertainer previous to the war, then went to work for the railroad as an operator during. Her first husband, and dancing partner, was killed in ’41 while in basic training in Texas. My mother was always dripping with something exotic and had an artful knack for turning a pig’s ear into a silk purse.” (Photo courtesy Carla Henson.)

United States at the time of the disappearance. It is believed that President Roosevelt was aware that Earhart and Noonan were quite probably in Japanese custody, but that he chose to avoid the issue because of strained relations between Japan and the United States and the isolationist policy that existed with the U.S. Congress at the time. It is further believed that the 1944 information and findings concerning Miss Earhart and Mr. Noonan were suppressed because of their possible bearing on the Presidential election of that year.

Literally hundreds of Pacific Island natives were interviewed during the four expeditions to Saipan and the Marshall Islands. Thirty-nine eyewitnesses, who were able to choose Miss Earhart’s photo from a series presented to them, were found. When the testimony of these witnesses is combined the story emerges:

Amelia Earhart and Frederick Noonan made a forced landing in the Marshall Islands in the vicinity of Jaluit and Mili Atolls. They were picked up by the Japanese and taken to Kwajalein, Marshall Islands, the Japanese headquarters for that area, and then transported to Saipan in the Marianas, Japan’s overall headquarters for the Pacific. Miss Earhart died of dysentery sometime between eight and fourteen months after her capture, and Mr. Noonan was executed after her death. They were buried in a common grave outside the perimeter of a small native cemetery south of the city of Garapan, Saipan.

Not aware that the remains of the “American man and woman flyers” had been removed in 1944, members of the 1961, ’62 and ’63 Saipan expeditions excavated around the same cemetery. In 1961, human remains were found, but a study by University of California anthropologist Dr. Theodore McCown indicated the bones represented four or possibly five people and were not those of Earhart and Noonan.

Wallace M. Greene, Jr., was a four-star U.S. Marine Corps general and the 23rd Commandant of the Marine Corps from Jan. 1, 1964 to Dec. 31, 1967. The Greene Papers is an edited volume of his personal papers during the time he served on the Joints Chief of Staff during the height of the Vietnam War. On Saipan in the summer of 1944, Greene was a lieutenant colonel and operations officer of the 2nd Marine Division, was unofficially credited with discovering Amelia Earhart’s Electra 10E in a Japanese hangar at Aslito Field, and was ordered by Washington to destroy it soon thereafter. He denied his nefarious role in the Earhart saga to his dying day.

What happened to Earhart’s Lockheed Electra 10-E ten-passenger airliner remains a mystery. Parts of a pre-World War II aircraft were recovered from Tanapag Harbor

-5-

Saipan, in 1960, but proved to be of Japanese manufacture. Some testimony exists that the plane was also taken to Saipan by the Japanese and was possibly destroyed in the 1944 U.S. invasion which leveled large areas of the island. Twenty-nine thousand of 30,000 Japanese troops were killed during the invasion along with hundreds of natives. The United States forces suffered more than 15,000 casualties.

Commenting on the Earhart “mission” a former member of U.S. military intelligence, who declines to be identified at this point, says, “If the Soviet Union had downed Francis Gary Powers’ U2 plane but not announced it for their own reasons, do you think the United States would have said that Powers was lost on a spy mission over Russian territory? The same principle applies to Earhart. If the Japanese didn’t announce her capture, the United States certainly was not going to make an issue out of it. Japan was ready for war. She launched the full-scale invasion of the China mainland just five days after Earhart and Noonan disappeared. Japan was militarily committed to that invasion and couldn’t afford an altercation with the League of Nations or the United States over what she had been doing to prepare the mandated islands of the Pacific for war. The truth is Japan was not ready to take on the United States until four years later.”

Goerner’s book in its closing chapter calls for an investigation by the U.S. Congress into the circumstances of Earhart’s disappearance. (End of KCBS press release.)

####

On the front page of the foregoing, it states, “Fred Goerner and Everett Henson Jr., mentioned in this release, will be available for recording interviews Monday morning, July 25 [1966], Studio E, KCBS Radio, Sheraton-Palace Hotel, San Francisco,” and recipients are advised that “Long-distance telephone-tape interviews will be available also.” I’ve never found any evidence that even a single media organization accepted KCBS’s invitation to interview either Goerner or Henson. Clearly, by 1966, our media’s aversion to the truth in the Earhart disappearance was already beginning its growth to the full metastasis we see today.

Congress has never done a real investigation of the Earhart disappearance. In an event that appears to have been completely suppressed from the public, in July 1968 Goerner appeared before a Republican platform subcommittee in Miami, chaired by Kentucky Governor Louie Broady Nunn.

In his four-page presentation, “Crisis in Credibility — Truth in Government,” Goerner laid out the highlights of the mountain of facts that put the fliers on Saipan and appealed to the members’ integrity and patriotism, doing his utmost to win them to the cause of securing justice for Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan. Nothing eventuated, of course, and I have the record of Goerner’s brief congressional encounter only because I briefly had access to his files, now housed at the Admiral Nimitz Museum in Fredericksburg, Texas, which continues to ban Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last from its bookstore.

Carla Henson

Agent of First Impressions

In a recent email, Carla Henson described her job as “Agent of First Impressions,” an inventive title I hadn’t heard before, as “running the front desk and lobby at Sacramento’s ABC television station, focusing on giving clients and customers what they are looking for, selling the station and sending them away with a ‘human touch.‘ The last impression can be as important as the first; we want them to come back.” Based on our correspondence, it’s quite evident that Carla is a valuable member of the ABC10 team.

Carla enjoyed a 30-year career working in sales and administration for Tower Records, spending the first 14 years in Sacramento, followed by 16 years at Tower’s Nashville, Tenn., headquarters before returning to Sacramento in 2001. “It is my good fortune to say that I got up every day for 30 years and loved my job!” Carla wrote of her Tower Records experience. “I traveled the world.”

Carla corresponded with Fred Goerner after her father’s death in 1982, and remains extremely interested in the Earhart case. She’s kindly forwarded many photos, documents and other war memorabilia her father left, and we doubtless will be hearing more from her in future posts.

![Fishing boat story 5 This story appeared at the top of page 1 in the July 13, 1937 edition of the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania)-Globe Times. “Vague and unconfirmed rumors that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan have been rescued by a Japanese fishing boat without a radio,” the report began, “and therefore unable to make any report, found no verification here today, but plunged Tokio [sic] into a fever of excitement.” The story was quickly squelched in Japan, and no follow-up was done. (Courtesy Woody Peard.)](https://earharttruth.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/fishing-boat-story-5.png?w=616&resize=616%2C352#038;h=352)

Recent Comments