Goerner and Devine reach out to Muriel Morrissey: Did Amelia’s sister know more than she let on?

Grace Muriel Earhart Morrissey, Amelia’s favorite childhood companion and her only sibling, is an often-overlooked character in the Earhart saga. Unlike Amelia, Muriel was blessed to live out a long, productive life, dying at 98 at her West Medford, Mass., home. She was a unique individual in her own right, and deserves to be remembered.

“Muriel Morrissey was a charter member of the Medford Zonta Club, a worldwide service organization of executive women in business and the professions, founded in 1919,” wrote Carol L. Osborne, who, with Muriel, co-wrote Amelia: My Courageous Sister, self-published by Osborne in 1987.

“During Muriel’s long teaching career,” Osborne continued in her tribute to Muriel that appears on the website of the Ninety-Nines, the elite women’s pilot group that Amelia co-founded with Louise Thaden in 1929, “she published numerous articles in professional education magazines, was a member of the Massachusetts Poetry Society and the author of several poems, including ‘First Day,‘ ‘To AE,‘ and ‘Labor-in Vain No More.‘

“In 1976, her ‘Bicentennial Reverie’ received a Freedom Foundation Award. She wrote a poem which was read at the dedication of a new school named for her sister Amelia, and a narrative poem, ‘By the Gentle Flowing Mystic’ as a feature of the celebration of Medford’s 350th anniversary.”

Grace Muriel Morrissey Earhart, Amelia’s beloved “Pidge,” passed away at 98 on March 2, 1998. “She was really a very sweet, gentle woman and she was really devoted to Medford,” her son-in-law Adam Kleppner told the Atchison Daily Globe. “She embodied a lot of old-fashioned virtues, responsibility, loyalty — things we seem to be in short supply of today.”

Muriel wrote an earlier biography of Amelia,Courage is the Price, in 1963, and in 1983 she wrote and self-published The Quest of A Prince of Mystic Henry Albert Morrissey “The Chief,” the biography of her beloved husband.

Muriel could never have dreamed the way her life would change after Amelia’s tragic loss, and we can only imagine how she agonized over her sister’s disappearance. The massive publicity, unwanted attention, false leads and dead ends that the never-ending search for her famous sister created must have brought her to the brink on many occasions. At least, this is the “conventional wisdom” about Muriel, as well as her mother, Amy Otis Earhart; George Putnam, Amelia’s husband; and Mary Bea Noonan, Fred’s widow.

It could well have been that way, but some researchers, including this one, have wondered whether Muriel, Amy, Putnam and Mary Bea could have been let in on the truth about Amelia’s Saipan fate by the feds and sworn to secrecy and silence in exchange for the kind of closure that families of missing loved ones long and pray for.

Telling the Earhart and Noonan families the sad truth would have made sense for the feds from a practical standpoint: With the Earhart and Noonan families fully informed, the government wouldn’t have to deal with the messy and noisy distractions they could have created in the media had they been kept on the outside of the establishment stonewalls that Fred Goerner nearly broke though during his early 1960s investigations.

We have Amy Otis Earhart’s statement to the Los Angeles Times in July 1949, in which she revealed that she knew almost precisely what had happened to Amelia: “I am sure there was a Government mission involved in the flight, because Amelia explained there were some things she could not tell me. I am equally sure she did not make a forced landing in the sea,” Amy said. “She landed on a tiny atoll – one of many in that general area of the Pacific – and was picked up by a Japanese fishing boat that took her to the Marshall Islands, under Japanese control.”

And five years earlier, writing to Neta Snook, Amelia’s first flight instructor, Amy left no doubt that she was quite well informed about her daughter’s fate, and we discussed this in our Dec. 9, 2014 post, Amy Earhart’s stunning 1944 letter to Neta Snook, which included this from Amy:

You know, Neta, up to the time the Japs tortured and murdered our brave flyers, I hoped for Amelia’s return; even Pearl Harbor didn’t take it all away, though it might have, had I been there as some of my dear friends were, for I thought of them as civilized.

Amy lived with Muriel in West Medford from 1946 until her death in 1962 at age 93, so it’s safe to assume that Muriel knew everything that Amy did. Thus, for the government to have officially shared the truth with the Earharts would not have been surprising.

After all, despite the media’s insistence that Amelia’s fate has been a “great aviation mystery” from the first moments of her loss, the truth about her Marshalls and Saipan presence and death has been an open secret since Goerner presented it for all to see in his 1966 bestseller, The Search for Amelia Earhart. Since Goerner’s book, 50 years of investigations have added a mountain of witness testimony that has illuminated the obvious for all but the most obtuse or agenda-driven.

Just when this may have occurred is anyone’s guess; they might have even been allowed to quietly bury Amelia and Fred in unmarked graves. No probative evidence has surfaced that supports this idea, but nothing we know precludes it, either. In fact, Muriel’s public statements to Fred Goerner, Thomas E. Devine and others in later years that she endorsed the Navy’s conclusions are far more surprising, in light of her mother Amy’s famous statements.

If a letter Goerner wrote to Muriel in 1966 is any indication, it’s clear the KCBS radio newsman didn’t believe that Muriel was privy to any inside information, at least at that time. That doesn’t mean Muriel hadn’t already been told about her sister’s sad end, only that Goerner didn’t think so. Below is his 1966 letter to Muriel, courtesy of Bill Prymak’s Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters, where it first appeared in the March 1998 edition

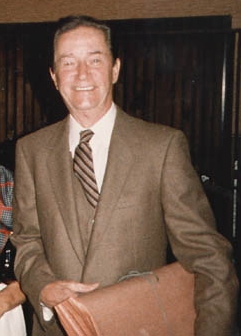

Fred Goerner, right, with the talk show host Art Linkletter, circa 1966, shortly before the establishment media, beginning with Time magazine, turned on Goerner and panned his findings, telling readers, in essence, “Move along, Sheeple, nothing to see here.”

“An Eminent Researcher’s Poignant Letter to Amelia’s Sister”

Mrs. Albert Morrissey

One Vernon Street

West Medford, Massachusetts

August 31, 1966

Dear Mrs. Morrissey:

Your letter of the 27th meant a great deal to me. I can’t begin to tell you how I have agonized over continuing the investigation into Amelia’s disappearance and writing the book which Doubleday is just now publishing. I know how all of you have been tortured by the rumors and conjectures and sensationalism of the past years.

I want you to know that I decided to go ahead with the book last December at the advice of the late Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz who had become my friend and helped me with the investigation for several years. He said, “it (the book) may help produce the justice Earhart and Noonan deserve.”

The Admiral told me without equivocation that Amelia and Fred had gone down in the Marshalls and were taken by the Japanese and that this knowledge was documented in Washington. He also said that several departments of government have strong reasons for not wanting the information to be made public.

Mrs. Morrissey, regardless of what the State and Navy Departments may have told you in the past, classified files do exist. I and several other people, including Mr. Ross Game, the Editor of Napa, California REGISTER and Secretary of The Associated Press, actually have seen portions of these files and have made notes from their contents.

This material is detailed in the book. I am sure that we have not yet been shown the complete files, and General Wallace M. Greene, Jr., Commandant of the Marine Corps in Washington, refuses to confirm or deny the testimony of many former marines that the personal effects of Amelia and Fred and their earthly remains were recovered in 1944.

Amelia, or “Meelie,” left, was two years and four months older than Muriel, known as “Pidge.” “We never played with dolls,” Muriel wrote, “but our favorite inanimate companions were our jointed wooden elephant and Amelia’s donkey. Ellie and Donk lived rigorous lives which no sawdust-filled, china-headed beauty could have survived. . . . We never slept until the two battered but faithful creatures were on guard at the foot of our beds.”

Please believe what I am saying. If justice is to be achieved, it may require your assistance. You know I have the deepest respect for Amelia and Fred. My admiration for their courage has no limits. They should receive their proper place in the history of this country. A San Francisco newspaper editor wrote the other day that Amelia and Fred should be awarded the Congressional Medals of Honor for their service to this country. I completely concur.

I shall be in Boston sometime toward the end of September or early October. I hope that I can meet with you at that time and bring you up to date on all of our efforts.

My very best wishes to you and “Chief.”

Sincerely,

Fred Goerner

CBS News, KCBS Radio

San Francisco 94105

Goerner had known Muriel since October 1961, when he traveled to West Medford, Mass., to ask her for permission to submit the remains he had recovered on Saipan during his second visit there, about a month earlier, for anthropological analysis. For a time, Goerner thought it possible that the bones and teeth he excavated during his second Saipan visit, in September 1961, might have been those of the fliers, but he was soon disabused of that idea when Dr. Theodore McCown determined that the remains were those of several Asians.

Before he engaged with Muriel and her husband, Albert, better known as “Chief,” Muriel told Goerner she believed that Amelia “was lost at sea,” and that “a crash-landing on the ocean was more likely than capture by the Japanese.” But after her meeting with the charismatic newsman, Muriel changed her mind, and sent letters to officials granting Goerner permission to have the remains evaluated.

Thomas E. Devine, the late author of Eyewitness: The Amelia Earhart Incident, one of the most important Earhart disappearance books, had his own ideas about where Amelia was buried, and he visited Muriel in West Medford in mid-July 1961 to appeal to her for information she might have had about Amelia’s dental charts.

Devine described his visit with Muriel as pleasant, and before he left, she even gave him a portrait of Amelia. On the back of the photograph, Muriel wrote: “To Thomas Devine, who is genuinely and unselfishly interested in Amelia’s fate, I am happy to give this photograph of her.”

Otherwise, she told him that many years of false and irresponsible claims had taken their toll on the family, and she had resigned herself to accepting the Navy’s version that Amelia and Fred were lost at sea near Howland Island. Muriel’s generosity to Devine was short-lived; two years later, in 1963, she refused to grant him permission to exhume what he was convinced was the true gravesite on Saipan.

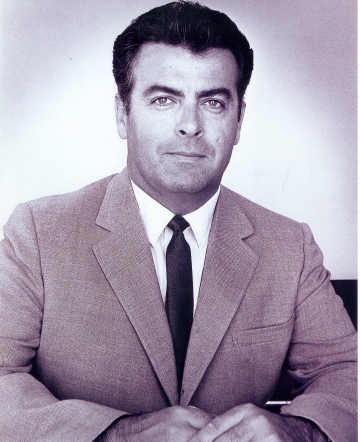

Thomas E. Devine, circa 1987, wrote about his visit to Muriel in his 1987 classic, Eyewitness: The Amelia Earhart Incident.

Devine’s visit with Amelia’s sister was memorable nonetheless, for reasons that could very well be directly related to the possible scenario suggested earlier. In a day filled with strange and unnerving occurrences, Devine only later realized he had been trailed — actually escorted — by ONI agents throughout his entire trip to West Medford.

In a scene oddly reminiscent of the day on Saipan in August 1945, when he was approached out of the blue and told to return to the states by airplane — an order he wisely refused to obey — Devine was picked out of a large crowd at the Boston train station by a cabby who told him he’d take him to West Medford for free. Without asking for Devine’s destination, the cabby deposited him within a block of Mrs. Morrissey’s house, saying, “This is as far as I go.”

When Devine asked the driver where Vernon Street was, the cabby pointed and told him, “That’s it, right up the hill. It’s that corner house.” When Devine said he was looking for “number one, Vernon Street,” the driver, as if clairvoyant, replied, “That’s it, the corner house on the hill, where Amelia Earhart’s sister lives.”

After their visit and just before Devine left, Muriel went to a window and raised and lowered a window shade to its full length. Saying she would return soon to say goodbye, she left the room to attend to her mother, who was bedridden and living in the Morrissey home. When Muriel left the room, Devine looked out the window. Standing a short distance from the house, he saw the same cabby who met him at the depot talking to another man.

Upon departing the house, Devine walked down the hill. The two men had disappeared. As he rounded the corner, looking for transportation back to Boston, the cab driver suddenly appeared, and directed him to the nearest stop on the MTA that would shuttle him back to Boston.

Stopping for lunch at the depot restaurant before taking the train for New Haven, Conn., Devine watched from the counter as two men and a woman entered and took a table at the near-empty restaurant. The woman then walked behind the counter where he was seated, and went into the kitchen with Devine’s waiter.

Devine said he paid little attention to their whispered conversation, but heard the woman ask the waiter for an apron. She then began serving the two men at the table behind Devine. Suddenly she told Devine, “You’ll have to sit at one of the tables or I can’t serve you.” Devine initially said nothing, but the woman persisted. He then agreed to move, as he wanted a cup of coffee. As he turned, Devine saw the cab driver and the man who had been talking to him outside the Morrissey home. He pretended not to recognize them, and they seemed not to notice him.

Muriel Earhart Morrissey, circa 1989, West Medford, Mass. Did she know the truth about her sister’s sad fate all along?

“After I was seated, the two men began a real show,” Devine wrote in Eyewitness. “The woman encouraged me to speak to the men about their foul language, but I declined; then they pretended to argue. ‘Here I invite you in for a drink,’ the cab driver roared, ‘but you don’t reciprocate!’ ” At their table, Devine saw three full beers in front of each man. Again the woman insisted that Devine speak up, but he refused. The cab driver then pounded on the table, threatening to beat up the other man. Suddenly, they left the restaurant.

“Amazingly, the woman urged me to go out and intervene, but I had seen enough of this ridiculous charade,” Devine recalled. “I was not about to be relieved of my briefcase. Instead, I left the restaurant by another door. Shortly, who should I spy amidst a group of passengers in the depot but the cab driver! As I looked toward him, he turned his head.

“Finally my train arrived,” Devine went on, “and I boarded, but there was the cab driver, also boarding. Thoroughly unnerved, I walked to the last car and stepped off just as the train started moving.” While he waited for the next train to New Haven, Devine said he decided to return to the restaurant “to risk a cup of coffee. The same waiter was behind the counter, but the ‘waitress‘ was gone.” Devine asked the waiter where the woman was, receiving only, “She left,” in response.

Devine boarded the next train and returned home without further incident. Fast forward to 1963, when he visited the Hartford station of the Office of Naval Intelligence for a second time, to determine if the ONI was still active in its investigation of his Earhart gravesite information. He was taken into an office where two men and a woman were seated. One of the men opened a safe to get the Earhart files, then pointed out passages for the woman to read, as Devine described in Eyewitness:

I was haunted; the woman looked familiar to me. Slowly, I came to the astounding realization that this woman was the “waitress” in the Boston depot! The woman must have sensed that I recognized her, for she immediately excused herself. Hastily the remaining ONI agent informed me that there had been no further investigation of Amelia Earhart’s grave. I left the meeting convinced that the people who had accosted me in Boston were agents of the Office of Naval Intelligence. Why their presence in Boston on the day of my visit with Mrs. Morrissey? I cannot say. Mrs. Morrissey did tell me that she had informed the Navy of my intended visit.

But why would the ONI trail me to West Medford? I don’t know. What was the purpose of the ONI agents’ peculiar antics in Boston? That I do not know, either. Perhaps they were trying to frighten me into curtailing my investigation.

The bizarre fiasco acted out in the Boston train depot restaurant by ONI personnel defied explanation, but it did expose the agency’s awareness and interest in Devine’s meeting with Muriel Morrissey. It also demonstrated that Muriel had a confidential relationship with the Navy, the roots and nature of which were never made public by the Earhart family.

Thus, we can still reasonably ask whether Muriel knew the truth about Amelia’s demise on Saipan, and when she knew it. The answer to that question, of course, will probably never be known.

Jim Golden’s legacy of honor in the Earhart saga

I don’t remember the first time I heard the late Jim Golden’s name; of course, it was in some way connected to the Earhart story. But I’ll never forget the reverent tones of respect that often punctuated mentions of him.

Within the closed confines of Bill Prymak’s Amelia Earhart Society in the 1990s and early 2000s, before the AES lost several notable researchers to the grim reaper and began its descent into oblivion as a viable entity, Golden enjoyed a special status as an iconic character, a mystery man who, some suspected, might have possessed unique knowledge about the Earhart case. Nowadays, one would be hard pressed to find more than a few in the AES who have heard of Golden, and fewer still that understand and appreciate his contributions.

In the May 1997 issue of the Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters, which I didn’t see until about 2005, when Prymak offered all his original editions to newer AES members in a collection of two very thick, bound volumes, he spelled out many of the whispered suspicions that often accompanied mention of Golden’s name.

Prymak’s lengthy article, titled “The Search for the Elusive ‘Hard Copy’ Continues: Maybe, just maybe via Jim GOLDEN?” drew heavily from a number of letters between Fred Goerner and Golden, mainly from the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, found in Goerner’s files at the Admiral Nimitz Museum in Fredericksburg, Texas.

Most of Prymak’s eight-page piece is accurate in describing several intriguing exchanges between the pair, though it offers no smoking guns. But these conversations between Golden and Goerner strongly hinted that if anyone knew where the “bodies were buried” so to speak, Golden knew who they were and where to find them. (For more, see Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last, pages 342-347.)

Jim Golden, Washington, D.C., circa 1975. As a highly placed U.S. Justice Department official, Golden joined Fred Goerner in the newsman’s search for the elusive, top-secret files that would finally break open the Earhart case. During his amazing career, Golden led Vice President Richard M. Nixon’s Secret Service detail and directed the personal security of Howard Hughes in Las Vegas.

Golden initially contacted Goerner after reading The Search for Amelia Earhart in 1966, offering to help the KCBS radio newsman in his Earhart investigation, and together they pursued the elusive, top-secret Earhart files in obscure government locales across the nation. Although they didn’t find those files, Golden’s exploits became legendary in the Earhart research community.

The man whose fascinating career included eight years as a Secret Service agent assigned to President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Vice President Richard M. Nixon indeed knew much about the Earhart case. Among the still-classified secrets he shared with Fred Goerner was the early revelation that Amelia and Fred Noonan were brought to the islands of Roi-Namur, Kwajalein Atoll by air from Jaluit Atoll by the Japanese in 1937, a fact he learned from Marine officers during the American invasion of Kwajalein in January 1944.

Sometime in the late spring of 2008, since no one else seemed interested in doing it, I decided to contact Golden and perhaps find out the truth for myself about what he really knew about the Earhart case. Much to my surprise, Golden welcomed my initial interest and soon we became friends, bound by our mutual interest in the Earhart matter.

From his Las Vegas home, Golden recalled his days on Kwajalein, where he was a 19-year-old enlisted Marine photographer in the intelligence section of the 4th Marine Division. There he learned that Marine Intelligence personnel were sent into the Marshalls to interview natives about their knowledge of the two American fliers who landed or crash-landed there before the war. On Kwajalein in January 1944, Golden, who headed the criminal conspiracies division at the U.S. Justice Department from 1973 to 1982, was told by Marine officers about at least one Marshallese who confirmed Earhart and Noonan’s presence on Roi-Namur, though he couldn’t remember a name.

“The Marine Corps were very apparently assigned the effort to search for evidence of AE, being the first to retake the Marshall Islands,” Golden, who didn’t like writing emails, told me in his most extensive written message. “The Marine 4th Div. Intelligence Section, 24th Marines Intel Unit, interviewed a native who worked for the Japanese on Roi Island air strip in early February 1944 after it had been captured by that unit.

“The Marines wrote up a detailed report capturing the info that related that in 1937 two white persons, a male and female were brought by plane to Roi,” Golden continued, “the man with a white bandage on his head and the woman with short cut hair wearing men’s pants, who were taken across a causeway to the Namur Admin building. Three days later taken out to a small ship in the lagoon, which then departed. I read the report myself. This report would routinely be forwarded to 4th Div. Intel, then on to the U.S. Navy. This report must have been the first sighting of her capture by the Japanese by U.S. forces at that time.”

Jim Golden’s no-nonsense comments about FDR’s role in the cover-up of the truth in the Earhart disappearance were the subject of this story in the Jan. 3, 1978 Midnight Globe. Headlined “FDR’s Amelia Earhart ‘Watergate’ ” the tabloid story was sloppy with the details, but got the basic story right, thanks to the straight-shooting, politically incorrect Jim Golden’s love for the truth.

Golden’s recollection of a native witness report of a white male and female being taken to a “small ship” in the lagoon, “which then departed,” is likely accurate, and doesn’t necessarily mean the ship took them to Saipan. Since the evidence suggests Earhart and Noonan left Kwajalein by plane, they could have been taken aboard the ship for any number of reasons, and later flown off the island. (See Truth at Last, pages 162-163.)

During the next three years, this American patriot shared much of his unique past with me, revealing many still-classified stories including a bizarre, possible Soviet assassination attempt on Nixon during his visit to Moscow in 1959. Although he seemed quite open and quite willing to talk about his days in the Secret Service, Golden was always tight-lipped about his brief stint in the early 1970s as head of security for the eccentric Howard Hughes. I never pressed him to explain his reluctance to discuss his time with Hughes.

In an October 1977 Albuquerque (New Mexico) Tribune story on Golden, “Prober says Amelia Earhart death covered up,” Golden, then with the U.S. Justice Department, told reporter Richard Williams that President Franklin “Roosevelt hid the truth about Miss Earhart and Noonan, fearing public reaction to the death of a heroine and voter reaction at the polls. . . . What really bothers me about the whole thing is that if Miss Earhart was a prisoner of the Japanese, as she seems to have been, why won’t the government acknowledge the facts and give her the hero’s treatment she deserves?” Golden asked.

Shortly after the Tribune story broke, Golden was spotlighted in a front-page story in the Midnight Globe tabloid, headlined “FDR’s Amelia Earhart ‘Watergate’ “ that appeared Jan. 3, 1978. The story took many liberties with facts and even fabricated some of his quotes, Golden told me in June 2008, but he stood by his closing statement: “Earhart gave her life for her country, and it ought to have the good grace to thank her for it.”

In these two news stories, Golden joined Fred Goerner to publicly finger President Franklin D. Roosevelt as the major culprit in the Earhart problem. “Amelia Earhart was killed in the line of duty, and President Roosevelt refused to let it get out,” Golden told Midnight Globe writer Leon Freilich. “She was a spy for the Navy. She didn’t just ‘disappear’ as Roosevelt led the press and public to believe. Amelia Earhart was taking reconnaissance shots of Japanese naval facilities when her plane was forced down. She died at the hands of the Japanese.” More than once during our many phone conversations, Golden said that after those two stories came out, “many people in Washington, mostly Democrats,” were not pleased with his statements to the press, and began to treat him differently.

Shortly after Golden called Goerner in 1966 to offer his help to Goerner, he was soon contacted by a former Marine who told him he “helped to wheel Electra NR 16020 out of a locked and guarded hangar on Aslito Airfield” on Saipan in July 1944. “He wouldn’t give me his name or any further info,” Golden said in an e-mail, “so Fred and I could not proceed to use the info at that time.”

Private First Class James O. Golden, circa 1944. As a photographer assigned to independent duty in Marine Intelligence on Kwajalein in January 1944, Golden read a report by officers of the 24th Marine Intelligence Unit about a native on Roi-Namur who told them of two white people, a man and a woman, brought by Japanese airplane to Roi, the man with a white bandage on his head and the woman with short-cut hair wearing men’s pants.

In 1975, Golden told Goerner that Robert Peloquin, a former federal prosecutor and then president of Intertel, Inc., an elite organization composed of former FBI, CIA and IRS agents that provided internal security for private clients – was also a former Office of Naval Intelligence officer who claimed he had seen the top-secret Earhart files and confirmed that they reflected her capture by the Japanese and her death on Saipan. Golden set up a meeting between Goerner and Peloquin “sometime in the mid-’70s,” but when Goerner got to Washington, Peloquin backed out of the meeting because he “feared for his career,” according to Golden.

In June 2008, Peloquin, 79 and retired in Fairfield, Penn., agreed to a phone interview with me after Golden called him and they spoke for the first time in 30 years. Peloquin told me he was a beach master during his active-duty Navy years, from 1951 to 1960, then he attended law school and became a Navy Reserve Intelligence officer between 1960 and 1980. He said he’d seen several classified Earhart files while at ONI, was familiar with the 1960 ONI Report, and was sure that the files he viewed were not those declassified in 1967.

“It was the general consensus among Navy intelligence people that Earhart died under the aegis of the Japanese,” Peloquin said, “whether by execution or disease.” But he wouldn’t – or couldn’t – provide any details about the documents or the circumstances in which he viewed them, claiming he had taken “an oath” that was still binding, and he also claimed he didn’t “remember much” about their specific content.

In mid-June 2009, Golden was, incredibly, one of only five American veterans of the Battle of Saipan who returned to the island for ceremonies commemorating its 65th anniversary — events completely overlooked by an American media focused solely on the June 6 D-Day observances in Normandy, France.

At a campfire held for the ex-servicemen on June 18, Golden and the others shared their Saipan memories with local officials, historians and students. Golden, who didn’t bother to keep any record of the attendees’ names, challenged the skeptics’ claims that no documentation exists to support Earhart’s prewar presence on Saipan, citing Goerner’s work, the native eyewitnesses on Saipan and the Marshalls, and his own experience with Marine Intelligence on Kwajalein in early 1944. His moving speech brought a standing ovation from most in attendance. I found it so very moving and appropriate that, more than anyone, Jim Golden was the face and voice of the forgotten Saipan veteran 65 years after the key U.S. victory of the Pacific war.

Golden was extremely interested in everything related to the Earhart case, and he avidly read each new chapter of Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last as I completed and sent them for his review. This fine man constantly encouraged me in my work, understood the establishment’s aversion to this story better than anyone I’d met, and was among the best friends I’ve ever had, despite never meeting him face to face.

Sadly, Golden passed away unexpectedly at his home on March 7, 2011 at age 85. His father had lived well into his 90s, and Jim was in good health and not suffering any serious illnesses at the time. Still, he had told me he wasn’t expecting to match his father’s longevity, and urged me to hurry in my efforts to find a publisher for Truth at Last. It wouldn’t be until that summer that I found Larry Knorr and Sunbury Press, and yet another year before the book was published in June 2012.

I like to think that Jim watched it all from a comfortable spot on the Other Side, and perhaps he even had a hand in making it happen. We’ll never see the likes of Jim Golden again, and I hope someday we’ll meet in a much better place. For now, my Dear Friend, may you Rest in Peace.

A close look at Paul Rafford’s “Earhart Deception”

Today we continue our examination of Paul Rafford Jr.’s writings about what might have have transpired during the last hours of Amelia Earhart’s alleged “approach” to Howland Island, as well as other intriguing and controversial ideas he advanced over the years following his retirement from the NASA’s Manned Space Program in 1988. (Boldface emphasis mine throughout; italics Rafford’s.)

On Dec. 7, 1991 Paul Rafford was putting the finishing touches on his new piece, “The Amelia Earhart Radio Deception,” which appeared in the March 1992 issue of the Amelia Earhart Society Newsletter. “The theory presented herein represents a major digression from the commonly held belief that Earhart was in the vicinity of Howland Island when her voice was last heard on the air,” he wrote. “It proposes that the radio calls intercepted by the Itasca were actually recorded by Earhart before she left the United States, to be played back at the appropriate time later on by another airplane.”

Fifteen years later, Paul presented his evolved theory of an Earhart radio deception as an entire chapter, or “Section 7,” as he called it, in his 2006 book Amelia Earhart’s Radio. That’s our focus for this post — Section 7, edited only for style and consistency, with a few photos added for your reading enjoyment.

“The Earhart Radio Deception”

The Earhart deception was designed to convince the world that she and Noonan were unable to locate Howland either visually or by radio; Itasca Radioman Bill Galten was not convinced. In 1942, after he came to work for Pan Am, he expressed his professional opinion to me, “Paul, that woman never intended to land on Howland!”

She had failed to answer any of his more than fifty calls or even tell him what frequency she was listening to. But to make sure, he called her on all his frequencies. Her method of operating was to suddenly come on the air without a call-up, deliver a brief message and be off, all within a few seconds. In fact, she was so brief that the Howland direction finder never had a chance to get a bearing. Also, every one of her transmissions was such that it could have been recorded well beforehand by a sound-alike actress. Even the Navy’s official report states, “Communication was never really established.”

Itasca heard approximately nine radio transmissions on 3105 kHz. They were divided into two groups separated by an hour. Messages in the first group, transmitted around sunrise or earlier, were weak or almost inaudible. The second group were loud and clear as though the plane was nearby. Chief Radioman Leo Bellarts later declared he felt that if he stepped out on deck he would hear the Electra’s engines.

Paul Rafford Jr., 95, the elder statesman of Earhart researchers. As a Pan Am radio flight officer from 1940 to 1946, Rafford flew with many people who knew Fred Noonan, Amelia’s navigator during her last flight, and he is uniquely qualified as an expert in Earhart-era radio operational capabilities.

The above suggests that the two groups were transmitted from different locations. The first group could have been sent from Canton Island where the Navy had set up a station the month before. The second group could have been sent from a nearby ship or Baker Island. The system worked well and the deception was not detected aboard Itasca or by later investigators. However, there is an important clue that indicates the transmissions were not “live.”

Listeners noted that there was a change in the voice pitch between the earlier transmissions and the final transmissions. Those near Howland were higher pitched. They presumed Earhart was getting desperate. But the recording and playback machines of the mid-1930’s did not have the stability of modern equipment. As a result, the Howland area recordings were inadvertently played back at a higher speed than those from Canton. This made the diction sound more hurried. But listeners passed it off as simply proving that Earhart was becoming increasingly nervous at not finding Howland.

In addition to her unorthodox operating procedures, Earhart’s sound-alike asked for 7500 kHz. to use with her direction finder. But this frequency cannot be used with airborne direction finders. When she failed to get bearings she should have switched to 500 kHz, where Itasca was already sending for her. After 45 minutes of silence, during which Itasca called her frequently, she finally came back on the air.

However, it was only to announce that she was on the line of position 157-337 and would switch to 6210 kHz. Itasca never heard her again and the search began. Here are two possible scenarios to explain why Earhart never reached Howland.

Scenario No. 1

Earhart and Noonan were following their announced flight plan from Lae to Howland when he became incapacitated. In her ignorance about radio and navigation, she was unable to get in contact with Itasca or take bearings on the ship. Finally, she simply ran out of gas and fell in the ocean.

The flaw with this scenario is that it doesn’t jibe with published accounts of Earhart’s radio expertise. For example, in Last Flight she describes flying along the routes of the Federal Airways System. She had no trouble communicating with the government radio stations and tuning in their navigation aids.

Scenario No. 2

We’ll never know when Earhart lost faith in Noonan’s navigation but the first indication was during their arrival over Africa after crossing the South Atlantic. She failed to follow his instructions and ended up landing at St. Louis, 168 miles north of Dakar.

After leaving Lae, she could have navigated visually by using the islands below as check points. But her Nukumanu Islands sighting is the only position report to be found in the records. After over flying them at sunset, she signed off on 6210 kHz. with Harry Balfour at Lae, and Alan Vagg at nearby Bulolo. Then, she could have turned toward Nauru, 525 miles east-northeast. She had received a message the day before that it’s giant lights, used for mining guano at night, would be turned on for her. Later, listeners on the island heard her say on 3105 kHz. that she had their lights in sight.

Had she been following a direct Lae-to-Howland track, she would have been far too south to see them. There were only four airfields in that part of the Pacific that could have accommodated Earhart’s plane. They were 1) Lae 2) Howland 3) Rabaul on New Britain and 4) Roi Namur in the Marshalls. But Roi Namur was the only one Earhart could reach without Noonan’s help.

After passing Nauru, Earhart could have headed for Jaluit in the Japanese-occupied Marshalls. She could have picked up its high-powered broadcast station and homed in on it after sunrise. Noonan should have known about the station because Pan Am on Wake Island used it to calibrate their own direction finder. Then, after overheading the station she could use a bearing from it to find the only land-plane airport in the Marshalls, Roi Namur. But would she have been so eager to land there had she known the Japanese were about to go to war with China?

Ten points to the Earhart Radio Deception:

– She was quick to reject Pan Am’s offer to track her across the Pacific with its direction finding network.

– She told Harry Balfour that neither she nor Noonan knew morse code.

– She signed off with Harry Balfour at sunset on July 2nd, even though he offered to stay in contact with her until she had established communication with Itasca.

– She never replied to any of Itasca’s numerous calls, done so on all of its frequencies.

– She never announced to the Itasca what frequency she was listening to.

– She never called up the Itasca before she transmitted a message.

– She never stayed on the air long enough for the Howland direction finder to try and get a bearing; never more than seven or eight seconds.

– She requested 7500 kHz from Itasca for bearings, even though her direction finder had been calibrated in the 500 to 600 kHz band.

– She never attempted contact with Itasca after she tuned in on 7500.

– She made no further attempt to contact Itasca, or ask the ship for another direction finding frequency.

Another look at the original flight plan that targeted Howland Island, the “line of position” of 157-337 Amelia reported in her final message, and the close proximity of Baker Island, just southeast of Howland, as well as the Phoenix Group, farther to the southeast. which includes Canton Island, as well as Nikumaroro, formerly known as Gardner Island, of popular renown.

Although we have no absolute proof that the flyers were Earhart and Noonan, thru the years investigators have turned up undeniable evidence that two Caucasians did land in the Marshalls before World War II.

One theory is that Earhart was supposed to secretly land on Canton and wait to be picked up. In early June, the U.S. Navy had hosted a solar eclipse expedition on Canton and left behind a radio station and personnel. They could have taken care of the flyers until the Navy was ready to find them. Under the guise of looking for Earhart, our Navy would have an excuse to make a survey of the mid-Pacific islands in preparation for World War II. Believe it or not, their navigators were working with outdated charts based on early 19th century whaling ship reports. When the survey was finished, she and Noonan could be “found.”

But suppose she had panicked at the idea of flying nearly 3,000 miles while depending on Noonan’s navigation? She had already missed Dakar by ignoring his order to change course. Lacking faith in his navigation, there was only one landing field in the mid-Pacific that she could reach by herself using her radio direction finder – Roi Namur. But, it was in the Japanese held Marshalls. After passing abeam Nauru, she could reach it by tuning in the Jabor broadcasting station on Jaluit that operated from early morning until late at night. In fact, the Pan Am direction finder at Wake used it to calibrate their own direction finder. After over-heading Jabor, she could follow a bearing from the station to reach Roi Namur.

The flyers had passed Nauru before midnight and Jabor was only 420 miles farther. With sunset still hours away, they would have to slow to their minimum air speed and circle until daylight. But fate intervened and they never landed at Roi Namur.

After delivering my Earhart speech at a Christmas gathering, a man came up to me and introduced himself. During the 1990’s he had been an Air Force civilian worker on Kwajalein. His work was at Roi Namur so he commuted daily by air. One noon he was walking about the island when he met a friendly old Marshallese who spoke good English. He had come back to visit his boyhood home. My friend asked him if he had ever seen any white people on Roi before World War II. To his surprise the old man said, “Yes!” and related his story. When he was a young boy he had seen two white people being loaded aboard an airplane and flown away.

One of the facts that tends to support Scenario No. 2 was the comment made by Secretary of the Interior Henry Morgenthau, Jr. to his colleagues that slipped out from under the veil of government secrecy: “She disobeyed all orders!” Morgenthau was recorded as saying in a telephone conversation. What orders could a private civilian have disobeyed that would upset a cabinet officer?

Two men who knew far more than they ever revealed about the fate of Amelia Earhart: Secretary of the Interior Henry Morgenthau, Jr. (left) and President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in 1934. Neither was ever called to account for his role in the Earhart disappearance, her death on Saipan or the subsequent cover-up that continues to this day.

With regard to landing on Howland, Itasca Chief Radio Officer Leo Bellarts remarked to Fred Goerner that although Earhart might get down OK, he didn’t see how she could ever take off through the thousands of nesting gooney birds. Yau Fai Lum wrote me that even dynamite failed to scatter them. He had gone aboard Itasca to get “a home cooked meal” when he heard a terrific boom! Looking back at the island he saw a mass of gooney birds suddenly become airborne. “They fluttered around for ten or fifteen seconds before settling down again,” Yau wrote. Air Corps Lt. Daniel Cooper advised his headquarters of the bird problem several days before Earhart’s arrival. But it had already been noted several months before during the airfield’s construction. Why did the “powers-that-be” not seem to be concerned about it?

Nevertheless, two airplanes actually did land on Howland, both during World War II. The first, based at nearby Baker, had engine trouble and was forced to use the Howland runways. The second carried a repair crew. Both planes eventually returned to Baker.

The Search

Here is the situation that emerges as we put the pieces together. First, Earhart was not on an espionage mission per se. There were government facilities, including ships, planes and professionals, who were much better equipped for spying than private individuals. However, we did need a good look at the Central Pacific before the outbreak of World War II. Like the Axis Powers in Europe, the Japanese were planning a war to conquer and dominate the Far East.

America was ill-prepared for a war in the Pacific. During the Earhart search our fleet was still operating with charts prepared by whaling captains a century before. We needed to get ready for war – and soon! Looking for America’s sweetheart would be an excellent excuse to bring those charts up to date, much quicker than depending upon individual ships and reconnaissance planes.

However, the Administration was faced with a problem. Not only were we just emerging from the Great Depression while still dealing with its problems, but to many isolationists Europe and its war clouds were a ten-day ocean trip away. Japan was even further. A popular song of the era expressed the feelings of many, “Oh the weather outside is frightful. But here inside it’s delightful. Let it snow! Let it snow! Let it snow!”

Also, George Washington’s comment in his farewell address was widely quoted: “Beware of foreign entanglements!” Privately, our government realized the need to be prepared to go to war in the Pacific. But although we couldn’t openly send a fleet to survey the area without raising extreme objections, we could send a fleet to look for Earhart. Even the isolationists would cry, “Go find our Amelia!” Meanwhile, under the pretense of looking for Earhart our Navy would update its charts and exercise the otherwise depression idled Pacific fleet. (End of “The Earhart Radio Deception” chapter.)

In his 1991 article I cited at the beginning of this post, presented in a question-and-answer format with Bill Prymak, Paul goes into far more detail in describing the covert operation he envisioned, as well as the logistics he believes were employed to facilitate it. Again, he begins by stating he believes Amelia never intended to land on Howland Island, citing Itasca Radioman Bill Galten’s well-known statement to him that Amelia”never intended to land on Howland.”

Pointing to the widely accepted idea that two-way communication between Amelia and Itasca was never established, Paul suggested that “all of the transmissions received by the ship could have been recorded weeks beforehand for playback by another plane. It could just as well have been a [Consolidated] PBY Catalina [flying boat] flying out of Canton Island.”

In my next post, we’ll delve further into Paul’s Earhart radio deception theory, as well as take a look at his unique and equally intriguing suggestion that the Earhart Electra was switched for another plane prior to their June 2, 1937 Miami takeoff. Much more to come.

“Silver container” recovered on Mili Atoll islet was indeed “hard evidence” in Earhart case (Part 2 of 2)

In my previous post we heard the accounts of Marshallese fishermen Lijon and Jororo as told to Ralph Middle on Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands, and passed on to Earhart researchers and authors Vincent V. Loomis and Oliver Knaggs in 1979. The story as related by Middle was that before the war they watched as an airplane landed on the reef near Barre Island, “two men” emerged from the airplane and produced a “yellow boat which grew,” climbed in and paddled to shore.

Hiding in the island’s dense undergrowth, Jororo and Lijon saw the pair bury a “silver container” on the small island, and soon the Japanese arrived. After one of them screamed upon being slapped during the ensuing interrogation, the fishermen realized one of the men was actually a woman. They remained hidden and silent, fearing for their lives.

Lorok, who had heard Lijon’s story in detail as a youth on Mili Atoll, owned Barre Island in 1981 and granted permission to Oliver Knaggs to search for the silver container buried by the plane’s crew before the war.

The existence of the silver container as described in Lijon’s account is supported by a little-known passage written by Amelia herself, in the final pages of Last Flight, her abbreviated 1937 book in which she chronicles her world-flight attempt. On page 223, Amelia wrote that she and Noonan “worked very hard in the last two days repacking the plane and eliminating everything unessential,” to help offset the burden the fully loaded fuel tanks would place on the engines, especially on takeoff from Lae. “All Fred has is a small tin case which he picked up in Africa,” Amelia wrote. “I notice it still rattles, so it cannot be packed very full.”

Knaggs returned to Mili in 1981 with a metal detector but without Loomis, hoping to locate Lijon’s silver container, and he soon met Lorok, “who owned the island of Barre and several others,” he wrote. Lorok told Knaggs that Lijon alone had seen the plane come down, but he’d died several years ago. Lorok said he was 11 years old, living on Mili, when he heard Lijon tell his story. How Jororo, a co-witness in the original story told by Ralph Middle, was no longer present in Lijon’s account as related by Lorok, has never been explained by Knaggs, Loomis or anyone else. The accounts as presented in the books by the two authors are all we have on this incident.

The results of the scientific analysis of this 7-centimeter piece of the buried artifact recovered by Knaggs confirmed that “in section the sample revealed what is described as a pin cover, rivet, and body of the hinge. . . . In general the microstructures are consistent with a fine, clean low carbon steel . . . indicating that good technology was used in its manufacture.”

Lijon was “out fishing in the lagoon near Barre, when he saw this big silver plane coming,“ Lorok told Knaggs. “It was low down and he could tell it was in trouble because it made no noise. Then it landed on the water next to the small island. He pulled in his fishing line and went quickly to see if he could help. When he got there he saw these are strange people and one is a woman. He hid then because he was frightened; he had not seen people like these. He watched as they buried something in the coral under a kanal tree. He could tell the man was hurt because he was limping and there was blood on his face and the woman was helping him. He waited there in his hiding place until he saw the Japanese coming and then he left. . . . Later we were told the people who crashed were Americans.” Lorok told Knaggs that Lijon later said, “The Japanese had taken her to Saipan and killed her as a spy. They were making ready for the war. They didn’t want anyone to see the fortifications.”

Knaggs found only one kanal tree when he searched Barre and two small, adjacent islands, and the intense heat and humidity made the going tough for his group. The next day, however, the wife of his native guide led them to another nearby island where she had seen a part of an old airplane when she played there as a child. They found no wreckage, but saw a “large, rotting trunk of a tree that could have been a kanal [years ago] and there was also a small kanal growing nearby,” Knaggs wrote. The detector soon responded, and about a foot-and-a-half down they found a “hard knot of soil that appeared to be growing on the root of a tree. Cutting into it, we discovered a mass of rust and what looked like a hinge of sorts.” Doubting that the shapeless lump could have once been the metal canister buried by the American fliers, Knaggs chipped away at his find but found nothing else.

Knaggs kept the hinge and brought it home to South Africa, where it was analyzed by the Metallurgical Department of the University of Cape Town. The results confirmed that “in section the sample revealed what is described as a pin cover, rivet and body of the hinge. In general the microstructures [sic] are consistent with a fine, clean low carbon steel . . . indicating that good technology was used in its manufacture.” Knaggs regretted not bringing the entire mass back for analysis, but “the hinge could have come from something akin to a cash box and could therefore quite easily be the canister to which Lijon had referred,” he concluded.

Lijon’s eyewitness account, as reported by Ralph Middle to Loomis and by Lorok to Knaggs, and reportedly supported by Mili’s Queen Bosket Diklan and Jororo, is among the most compelling ever reported by a Marshall Islands witness. The profoundly realistic description of the “yellow boat which grew,” combined with Knaggs’ recovery of the deteriorated, rusted hinge in a place where nothing of the sort should have been buried, lend additional credibility to Lijon’s story. Lorok told Knaggs that Lijon had spoken the truth about what he saw, and what could better explain the presence of a metal hinge on the tiny, uninhabited island, buried near a dead kanal tree?

The hinge wasn’t much to look at, of course, and will certainly never attain “smoking gun” status in the Earhart matter. It wasn’t sexy, it wasn’t Amelia Earhart’s Electra, her briefcase that was found in a blown safe on Garapan by Marine Pfc. Robert E. Wallack in the summer of 1944, nor even one of the many photos of Amelia and Fred in Japanese custody reportedly found by American soldiers on Saipan. Regardless of its appearance, its provenance qualified the old, rotted hinge as solid, hard evidence of the presence of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan on a small island near Barre Island, Mili Atoll in July 1937. I have no idea what has happened to this artifact, nor do I even know if Oliver Knaggs is still alive, though I’m nearly certain he’s now deceased. Anyone with information is kindly asked to contact me through this blog.

This set of four postage stamps issued by the Republic of the Marshall Islands in 1987 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Amelia Earhart’s last flight. The stamps (clockwise from top left) are titled: “Takeoff, Lae, New Guinea, July 2, 1937; USCG Itasca at Howland Island Awaiting Earhart; Crash Landing at Mili Atoll, July 2, 1937; and Recovery of Electra by the Koshu.”

The Marshallese people have never forgotten the story of the woman pilot, and it’s become a part of their cultural heritage. In 1987 the Republic of the Marshalls Islands issued a set of four stamps to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Amelia’s landing at Mili Atoll. (See earlier posts: “Frank Benjamin: ‘We are brothers in pain!’ ” Jan. 28, 2014; and “Dave Martin to the rescue,” Aug. 11, 2012.)

Thus, in the Marshall Islands, the fate of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan is far from the “great aviation mystery” it’s constantly proclaimed to be in the United States and most of the Western world. To the Marshallese, the landing of the Electra at Mili, the Japanese pickup and transfer to Saipan are all stone, cold facts known to all.

For Amelia Earhart, another unhappy birthday

Well, Amelia, another year has passed since Amy Otis Earhart brought you into this world in your grandparents’ Atchison, Kansas home on July 24, 1897, eons ago, in a much simpler and, some would say, far better America. Because you were so unexpectedly taken from us sometime after you turned 40, you’ll be forever young to those who remember and celebrate your life.

I’m sure you can read these comments or receive this message somehow, and I’m certain you’re in a place where the free flow of all information is enjoyed by all, and where no secrets exist. I’ll bet there’s plenty you’d like to tell us, but the rules up there prevent it.

Admittedly, it’s a stretch to think you might still be with us at 117 if a few things had gone differently for you and Fred Noonan, and had you reached that exclusive club, you’d surely be a contender for world’s-oldest-person honors. But considering the amazing feats you managed in your brief life that earned you nicknames like Lady Lindy and the First Lady of Flight, an equally lofty and hard-earned title 77 years later doesn’t seem impossible, does it? After all, Amy was an impressive 93 and lived the majority of her years before penicillin was discovered, and your sister, Muriel, made it all the way to the venerable age of 98 before she cashed in, so I’d say the odds were about even money that you could have been your family’s first centenarian.

In a highly publicized July 1949 interview, Amelia’s mother, Amy Otis Earhart, who died in 1962 at age 93, told the Los Angeles Times, “I am sure there was a Government mission involved in the flight, because Amelia explained there were some things she could not tell me. I am equally sure she did not make a forced landing in the sea. She landed on a tiny atoll—one of many in that general area of the Pacific—and was picked up by a Japanese fishing boat that took her to the Marshall Islands, under Japanese control.”

Of course, wishing you a Happy Birthday is just something the living do to make ourselves feel better; where you are, every day is far better than any grand birthday bash we could imagine, and birthdays there must be quite passé. For your devotees down here, though, at least for those who know the truth about what’s been going on for so long, it absolutely is another unhappy birthday, because nothing of substance has changed in the past year, and what little news we have ranges from the mundane to the depressing.

The big lie that your disappearance remains a great mystery continues to dominate nearly all references to you, often followed by another well-publicized whopper from TIGHAR that they’re just about to find your Electra on Nikumaroro, if only they can raise the money for the next search, ad nauseam. Such unrelenting rigmarole must bore you, but this and other ridiculous claims are what has passed in our despicable media for “Earhart research” since Time magazine trashed Fred Goerner’s bestseller The Search for Amelia Earhart in 1966.

Amelia at 7: Even as a child, Amelia Earhart had the look of someone destined for greatness. In this photo, she seems to be looking at something far away, not only in space, but in time. Who can fathom it?

You’ve likely heard that a young woman, Amelia Rose Earhart, a pilot and former Denver TV weatherperson who happens to have your first and last names but isn’t otherwise related, completed a relatively risk-free world flight July 11 following a route that roughly approximated your own. At least three others have already done this, all Americans: Geraldine “Jerrie” Fredritz Mock in 1964, Ann Pellegreno in 1967 and Linda Finch in 1997, so there was nothing notable in Amelia Rose’s flight, especially considering that she had the latest GPS navigational technology to ensure her safe journey.

Her motivation was to honor your memory, said Amelia Rose, who was the featured speaker at the annual festival held in your name at Atchison last week. I don’t attend these pretentious galas, and unless and until event organizers find the courage to come to terms with the truth of your untimely and completely unnecessary demise on Saipan, I never will. Last week she must have been making the rounds of the TV talk shows, as someone on FOX News announced she would be on soon, but I couldn’t bring myself to watch it.

If Amelia Rose actually cared a whit about your legacy, she’d learn the truth that so many insist on avoiding but is available to all. She would then use her public platform to stand up and call attention to this great American travesty and cover-up – rivaled only by the Warren Commission’s “lone gunman” verdict in the John F. Kennedy assassination in its mendacity, but unlike the JFK hit, completely ignored in the popular culture – and demand that our government stop the lies about her namesake’s true fate.

Unfortunately and all too predictably, based on what I know about this grandstanding pretender, Amelia Rose has never uttered a word that had any relationship to the truth about what happened to you 77 years ago.

Amelia’s younger sister by two years, Grace Muriel Earhart Morrissey of West Medford, Massachusetts, died in her sleep Monday, March 2, 1998 at the age of 98. Muriel was an educator and civil activist, participating in many organizations and benevolent causes. Muriel and Amelia were inseparable as children, sharing many tomboyish activities, riding horses together, loving animals and playing countless imaginative games.

Facts are stubborn things

Amelia Rose’s supporters say she doesn’t know about all the investigations and research that tell us that you and Fred Noonan landed at Mili Atoll on July 2, 1937, were picked up by the Japanese and taken to Jaluit, Roi-Namur and finally Saipan, where you suffered wretched deaths. This gruesome scenario, as well as the fact that our fearless leader at the time, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, refused to lift a finger to help you, much less inform the public that you were the first POWs of the yet-undeclared war to come, continue to be denied by the corrupt U.S. government and suppressed by our media big and small. But facts are stubborn things, and they don’t cease to exist because the local PTA, the Atchison Chamber of Commerce or Amelia Rose Earhart wishes it were so.

Many hundreds of books celebrate your remarkable life, but only a handful dare to reveal the facts surrounding your miserable demise at the hands of barbarians on that godforsaken island of Saipan. Now that the Japanese are among our best friends and allies in the Pacific Rim, we don’t want to offend their delicate sensibilities with public discussions of their World War II barbarities, do we?

Speaking of which, you might know Iris Chang, author of the 1997 bestseller The Rape of Nanking, which exposed the long-suppressed Japanese atrocities against the Chinese in December 1937, only months after your disappearance. Despite the book’s notoriety and widespread acceptance of its findings, the Japanese ambassador refused to apologize for his nation’s war crimes when Chang confronted him on British TV in 1998. In 1999 she told Salon.com that she “wasn’t welcome” in Japan, and she committed suicide in 2004.

We’re still not sure why Chang perpetrated the ultimate atrocity against herself, but it’s been said that the years of research into such horrific subject matter disturbed her greatly. The parallels are obvious, but the depravities the Japanese committed against the Chinese, despite the overwhelming numbers of the murdered, don’t rankle Westerners nearly as much as the mere consideration of what befell you and Fred on Saipan. Chang may have been unpopular in Japan, but her work was celebrated by the U.S. media, which avoids anything or anyone that hints at the truth about you like the plague.

The Rape of Nanking, Iris Chang’e 1997 bestseller that exposed the pre-World War II depravities of the Japanese military, was embraced by the U.S. media, which continues to suppress, deny and ignore the truth about that same Japanese military’s atrocities against Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan on Saipan.

Amelia Rose may not know the sordid details, but she’s heard the story and has shown no inclination to learn about the truth, falsely marginalized as an “unsubstantiated fringe theory” for many decades by our trusted media. So at best, Amelia Rose is among the willfully ignorant about you; this strain of ignorance is just another form of cowardice, another excuse to avoid the truth, and of course it’s dishonesty in spades.

How can I say this so blithely? At last year’s Amelia Earhart Festival, an Earhart researcher engaged Amelia Rose, on hand to collect another dubious honor, in a conversation that began well but abruptly turned to ashes when he brought up the subject of your death on Saipan. Amelia Rose, upon hearing this, flew from this man as if he had leprosy. Almost a year earlier, she ignored my email missives that not only politely informed her of the truth, but offered her a free copy of my book, Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last.

So Amelia Rose Earhart, rather than being a special person, is just one of many hundreds of similar mainline media lemmings who assiduously avoid the truth. Those who aren’t part of the solution are part of the problem, and excuse me if I repeat myself, but they are cowards as well.

So the lies continue without surcease, and 99.99 percent of the public continues to hear, read and without reservation buys the myth that your disappearance remains among the “greatest aviation mysteries of the 20th century.” A few of us know better, and are doing our best to rectify this appalling situation, but we aren’t having much success. Few will admit it, but the word has long been out that it’s not acceptable to talk about what really happened to you. Nobody wants to hear it, so it’s fallen to outsiders like this writer to do justice to your story. We’re called conspiracy theorists and wing nuts, and are strenuously shunned.

So Amelia, that’s how it looks to at least one of us down here on your 117th birthday. Sadly, you and Fred Noonan are as far from realizing Fred Goerner’s “justice of truth” as ever, and there’s nothing coming from our government that gives us the slightest glimmer of hope. But the difficulty of this mission doesn’t deter those of us who truly believe in the worthiness of the cause. And so we continue.

![Fishing boat story 5 This story appeared at the top of page 1 in the July 13, 1937 edition of the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania)-Globe Times. “Vague and unconfirmed rumors that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan have been rescued by a Japanese fishing boat without a radio,” the report began, “and therefore unable to make any report, found no verification here today, but plunged Tokio [sic] into a fever of excitement.” The story was quickly squelched in Japan, and no follow-up was done. (Courtesy Woody Peard.)](https://earharttruth.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/fishing-boat-story-5.png?w=616&resize=616%2C352#038;h=352)

Recent Comments