Was Earhart Electra found on Canton Island in ’37?

Researcher Woody Rogers recently forwarded an old newspaper story I’d not seen before, from a paper whose pages lacked any datelines or folios for easy identification, but which could only have been the Charleston (South Carolina) Evening Post, the only Evening Post operating in the United States in 1939. *

This provocative screed, published as early as July 1939 but possibly later that year (based on other stories on the page), would have the local South Carolinians, and by extension, the entire world, believe that Amelia Earhart’s Electra had “washed up” on Canton Island in the Pacific, minus Earhart and Fred Noonan, of course, during the July 1937 Navy-Coast Guard search, and that the Navy kept the news from the public.

Here’s the story, presented as best I can to retain some of the original, while adding some informative images (boldface emphasis mine throughout; caps emphasis in original; please click on images for larger views):

message was suppressed, but never denied. A few days afterward, the navy abandoned the search that cost the government hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Take Over Island

And by a rare coincidence, the United States government over the indignant protestations of European powers, TOOK OVER CANTON ISLAND A FEW WEEKS LATER.

Why should America want this insignificant island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean? Why should this country have risked certain diplomatic relationships for the right to possess this deserted bit of land?

And why, above all, was the order given to send virtually the entire Pacific fleet on an extensive manhunt when the Oriental situation was ready to boil over at any moment?

What About Data

Was Miss Earhart’s mission as innocently scientific as the world was led to believe? And what was the nature of the scientific data she hoped to gather ostensibly for Purdue university? Exactly what she and Noonan were after has never been revealed. The purpose of her journey was cloaked simply with the mysterious phrase, “scientific observations.“

Why did the government permit her to take off in the first place, inasmuch as the department of air commerce [sic] publicly frowned on the flight and doubted its scientific value? And why, then, did the government immediately order most of its Pacific fleet, along with scores of navy fliers, to seek the missing plane when word was first received that it was lost?

Search First of Kind

Never before in the history of transoceanic flying had such a search been ordered?

Why? the world new asks.

The public may never know the real answers. We may only guess the exact fate of

(Continued from page one)

Frederick Noonan?

If the Earhart flight were an innocent scientific excursion, why should the navy want to keep secret the fact that the airplane was beached in this this lonely island in the middle of the Pacific? What was there to be gained by such secrecy?

On the other hand, if Miss Earhart had in her possession important diplomatic information picked up on her tour of the globe, would it not be to the great advantage of this country to remain forever silent on the discovery of the airplane? And if silence was so important, wouldn’t it be logical that the island which contained the only evidence of Miss Earhart’s tragedy be taken over and held by the United States government?

May Not Be Answered

The entire situation is rife with questions. Questions which will probably never be answered officially.

It must be borne in mind that at the time of the Earhart flight, conditions in the Orient were none too secure. Most Americans took an aloof stand on the Sino-Japanese war. America will never war with Japan, it was said. But the navy knew better. The navy was taking no chances. There were Americans in China, and they were there because there were extensive American holdings in the Orient

The entire Pacific fleet was hovering in Oriental waters at the time. It left the danger zone ONLY LONG ENOUGH TO SEARCH FOR MISS EARHART’S PLANE [sic].

Earhart’s official flight plan, 2,556 statute miles from Lae, New Guinea to Howland Island. The 337-157 line of position, or sun line, passed through the Phoenix Islands, near Gardner Island, now known as Nikumaroro, and the popular false theory is in part attributable to this. Note location of Canton Island (far right just under USCG Itasca and Winslow Reef), in the same general area as Gardner, McKean and Enderbury Islands in the Phoenix group. Map taken from Earhart’s Flight Into Yesterday: The Facts Without the Fiction, by Lawrence Safford, with Cameron A. Warren and Robert R. Payne.

Hypothetical Case

Let’s study a purely hypothetical case.

An American flier has won the hearts of the world. The flier is better beloved because she is a woman, and her soul is in aviation. She has been successful in a number of previous flights. And now she is contemplating a round-the-world flight.

In various capitals of the world, agents of the government have obtained secret military information, valuable to American authorities. It is sometimes difficult to get such information safely back to the state department [sic] without interference by outside countries.

Suddenly the government sees and ingenious way of obtaining the information, bringing it back for expert study in Washington. What could be more innocent than a round-the-world flight by one of America’s most popular heroines? Who could possibly suspect such a woman of ulterior motives?

So arrangements are made. The government officially frowns on the flight but issues the license. All part of the plan. It is announced that the mission is a scientific one, but it is never deemed necessary to announce precisely what the nature of the scientific investigation is.

No Embarrassing Papers

As the flier speeds around the globe, she is greeted by hundreds of persons wherever she stops. She is cheered all along the way. There are no embarrassing papers to be filled out. No questions to answer, passports a mere formality. That is one of the courtesies governments extend to daring fliers of another nation.

But in some of the crowds are secret government agents. With absolute safety, they slip her maps, charts, notes bearing important military secrets, obtained in devious ways known only to agents.

Meanwhile. her own nation is watching with keen interest the success of the flight. Everyone hopes she succeeds, but state department officials have a double reason for praying for the success of the undertaking.

The flier is on her last long hop. She has everything she wants. Everything her government is waiting for. And then, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, something happens. There is a frantic flash from her radio. Something has gone wrong. She is overdue. Nothing more is heard.

AND IMMEDIATELY ALMOST THE ENTIRE PACIFIC FLEET IS DISPATCHED TO FIND HER.

Aerial view of Canton Island in 1945 showing SS President Taylor grounded in an entrance to the atoll, above left. Canton Island (from Wikipedia, also known as Kanton or Abariringa), is the largest, northernmost, and as of 2020, the sole inhabited island of the Phoenix Islands, in the Republic of Kiribati. It is an atoll located in the South Pacific Ocean roughly halfway between Hawaii and Fiji. Canton’s closest neighbor is the uninhabited Enderbury Island, 63 km (39 mi) west-southwest. The capital of Kiribati, South Tarawa, lies 1,765 km (1,097 mi) to the west. As of 2015, the population was 20, down from 61 in 2000.

Logical Answer

Wouldn’t that be logical? Might not those secrets be more important than keeping a full patrol in Chinese waters?

Wouldn’t it be exceedingly dangerous for a vessel of another power to come upon whatever documents her plane contained?

Word came once that a message had been received from Miss Earhart, giving her position after she was forced down. It was some distance north of Howland Island where she was expected to land. But navy officials must know that this message DID NOT COME FROM MISS EARHART BECAUSE HER RADIO COULD NOT SEND MESSAGES IF IT WAS AFLOAT.

That both Miss Earhart and Frederick Noonan are dead the world has little doubted. THE NAVY KNOWS. There was apparently no sign of either flier when the ship [sic] washed up on the beach of Canton Island.

Whatever happened, whatever information Miss Earhart was carrying back to her government, the world may never know. But a few people know that Miss Earhart’s craft was found. And for them the mystery only becomes deeper, less fathomable. (End of Evening Post story.)

The best the Evening Post could to do identify its source for this potentially world-changing story was to write, “The wireless message was seen by a member of one of the crews who said it was never denied.” Thus, anyone vaguely familiar with the Earhart disappearance and able to read at a high school level — which should be all readers of this blog — can easily discern the bogus nature of the Canton Island claim.

This story is pure disinformation, rife with innuendo and wild speculation meant to confuse readers, sell papers and, most importantly, further obscure and hide the Marshall Islands-Saipan truth. Earhart’s Saipan fate was almost certainly known to Navy Intelligence and thus FDR and those closest to him, possibly within the first few months of the fliers’ disappearance — though how this information first came to them remains uncertain. The story itself tells us the government knew the truth, and it’s so poorly written than its stink is impossible to ignore.

It was all to no avail, as this particular Earhart propaganda operation was a miserable failure. The Canton Island claim got no traction, and wasn’t picked up by any other newspapers, books or publications that I’m aware of. A search of websites for Canton Island has yet to uncover any mention of the idea that the Earhart Electra “washed ashore” there in July 1937, or any other time.

The story was so transparently bad that FDR’s central planners didn’t dare put in the New York Times or The Washington Post, instead opting for a trial run in the relatively obscure Charleston Evening Post. Further, a web search for the writer of this travesty, one Norman Arthur, produces zero results, which strongly suggests he never existed.

Attempting to dig deeper, my sincere, good faith query to the local Charleston librarian who has access to the old Evening Post archives was rudely ignored — frustrating but not unusual in this line of work — but I believe Norman Arthur was a fake name attached to this fake story. This phony claim ranks among the lowest scrapings in a still-growing 84-year-old trash bin of “Earhart mystery” bilge, and made absolutely no dent in the public consciousness, then or ever.

Nonetheless, the 1939 Evening Post story is notable, even remarkable, for one important reason. More than any reports about the disappearance up to that time, just two years after Earhart’s loss, it emphatically demonstrates that the U.S. government was actively engaged in media manipulation, disinformation and propaganda, despite the fact that virtually no one publicly questioned the government’s crashed-and-sank verdict at that time. The truth was known in the White House, and FDR wasn’t about to let the public know of his perfidy in the Earhart matter, when he abandoned America’s beloved First Lady of Flight, leaving her to the barbaric mercies of the Japanese on Saipan.

As I wrote in Truth at Last (pages 322-323):

If the American public had learned of the abandonment of Amelia Earhart— one of the most admired and beloved figures in our history—on Saipan by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1937, his transformation from popular president to national pariah would have been instantaneous, his political future reduced to ashes.

[*Editor’s note: March 10, 2022 update: The Charleston Library archivist has informed me that the foregoing story, which I was so sure came from the Charleston Evening Post, actually did not. She performed a thorough search of the paper’s archives to determine that fact, as well as that no record for Norman Arthur existed in the paper or in any Charleston listings in 1939. I appreciate and accept her findings, and also apologized for my impatience.

This doesn’t change anything else about the story, except to tell us that the Charleston Evening Post is off the hook for committing gross journalistic malpractice, at least in this case. I’ll keep you updated on any new information that can shed light on who actually was responsible for this travesty.

March 11 update: Woody Rogers replied and said the page he sent came from the Minneapolis Star, sometime in 1939. I searched the online archives and can’t find the page at this time. I asked Woody, whose files aren’t available right now, to let us know where the story came from as soon as he can, if possible.]

March 12 update: As requested by Les Kinney, below is the front page of the publication from which the above story came, minus the folio or banner at the top, which normally identifies the newspaper or publication. The page-wide headline also appears unusual. We await further developments.

Billings’ latest search fails to locate Earhart Electra

David Billings recently returned from his seventeenth trip to East New Britain in search of the Earhart Electra, and again he was unable to find the hidden wreck that he believes is the lost Electra 10E that Amelia Earhart flew from Lae, New Guinea on the morning of July 2, 1937.

Billings’ New Britain theory is the only hypothesis among all the various possible explanations that varies from the truth as we know it, but which presents us information and poses questions that cannot be explained or answered. Unless and until the twin-engine wreck that an Australian army team found in the East New Britain jungle 1945 is rediscovered, this loose end will forever irritate and annoy researchers who take such findings seriously.

Readers can review the details of Billings’ work by reading my Dec. 5, 2016 post, New Britain theory presents incredible possibilities. You can also go to Billings’ website Earhart Lockheed Electra Search Project and see “Earhart’s Disappearance Leads to New Britain: Second World War Australian Patrol Finds Tangible Evidence” which offers a wealth of information on this unique and fascinating theory.

Billings has sent me a detailed report on the events of the last three weeks, and it’s presented below. I wish he had better news, as this aspect of the continuing Earhart search is one that screams for resolution, unlike the others, which are all flat-out lies and disinformation, intended only to keep the public ignorant about Amelia’s sad fate. (Boldface emphasis mine throughout.)

SEARCHING FOR THE ELECTRA AND FOR AMELIA AND FRED

by David Billings

The Start

Our last expedition started on Friday, June 2, when the six members of the Australian team met at the Brisbane International Motel on the Friday evening prior to the flight out of Brisbane for Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea on the morning of Saturday, June 3.

We flew from Brisbane for three hours and went into transit at Port Moresby, then on to the flight which is “nominally” to Rabaul but actually Kokopo and arrived at Tokua Airport after an hour and 20 minutes, on time, and then by mini-bus to the Rapopo Plantation Resort just outside of Kokopo, which was the base for our “equipment and rations” gathering over the next two days.

The local singing group welcomes David Billings to Rapopo Plantation Resort. (Photo courtesy David Billings.)

Shopping

The hired HiLux vehicles arrived and Sunday and Monday was spent on shopping for the major items from prepared lists and boxing all the goods up and storing them in the rooms. Money changing at the banks in Kokopo and final shopping was Tuesday for odds and ends.

The U.S. team members arrived at the Rapopo on Monday, June 5, and after their hectic flight schedule relaxed on the Tuesday ready for the road trip on Wednesday.

The Journey to Wide Bay

The road trip with all 10 members was carried out in three Toyota HiLux Dual Cab 4WD’s with diesel engines. We had walkie-talkies for contact during the drive. The road we had planned on was to be approximately 160 kilometers (99.4 miles) and we expected to be able to do this in about four and-a-half hours. The actual time was seven hours over very rough roads and with a planned one major river crossing and several minor river crossings. In the event, due to finding one road impassable, we were forced to ford a quite wide and substantial river which we know from previous trips can be in flood quite rapidly as it has a large watershed area stretching up into the Baining Mountains.

The supposed “sealed” roads out of Kokopo through small villages towards Kerevat town were a nightmare with potholes every few yards and the daily multitude of vehicles were weaving in and out of the potholes and wandering all over the road to avoid the holes.

A good 10 kilometers out of Kerevat town, a turnoff towards the village of Malasait brought us onto the very rough tracks that we were to use for the rest of the journey. This rough track constitutes the major part of what is euphemistically called the “East New Britain Highway.” For a detailed look at the Gazelle Peninsula in relation to the Billings search, please click here.

The Gazelle Peninsula forms the northeastern part of East New Britain Province. Billings said the route from Kokopo to Wide Bay (below southern part of map, not labeled) is “mainly over very rough logging tracks.”

On the Highway

All went well over the awful rough roads until about the halfway point whereupon we came across a gigantic mudslide over a stretch of the “highway” on a downslope about 100 meters long, with ruts in the mud about 500 millimeters (19.6 inches) deep. There was a truck there which they had shed the load off of it and copra bags littered the drains as they had strived to get the truck through and they were picking the bags up on a long pole when we got there. Rain water had gone completely over this section and washed the road out. After throwing rocks into the deepest rutted sections and pushing the loose mud down also, we managed to get through this area in four-wheel drive. We had to remember this section of “road” and prepare for it for the return journey.

Shortly after this, we crossed the Sambei River No. 2, in a wide sweeping arc with water just over the wheel hubs which allowed us to stay on the shallowest parts and then continued on the way.

At this river crossing we had met up with a local man who said he was going to the Lamerien area and we followed him along a newly cut forestry road which joined up with the old road near to the turn-off to Awungi, then we entered the steep descending curves down into the Mevelo River Valley and expected to turn off to the right to follow the track through the Mumus and Yarras River Valleys. However, our guide drove straight ahead to a security guard post leading into the Palm Oil Plantation, sited on the northern side of the Mevelo River. On realizing that we were being led into the Palm Oil Plantation the expectation then was that the bridge over the Mevelo which we could see “not completed” in Satellite views must then be “completed,” which would mean we could cross the wide Mevelo River with ease.

The Mevelo River

After driving through the Palm Oil roads for about 40 minutes we came to the Mevelo River and our hopes were dashed! There was no bridge. We had seen a bridge with a very nearly completed driving span in the satellite pictures with but one span to be completed. What we were now looking at was a damaged bridge with no roadway across the pylons. The Mevelo River is a very fast flowing river in flood and an earlier flood had obviously caused the bridge supports to move and the bridge had collapsed.

The bridge was down, destroyed by the “mighty” Mevelo at some time in a flood. Several of the old shipping containers that had been used as ballast cans for rocks to hold and support the concrete bridgeworks had been moved out of position by the strength of the flow of water down the Mevelo River and now we were left with a choice — we must now ford the river or turn back.

Luckily, while we had a rest stop close to the access road to the river, I had seen two Toyota Land Cruiser troop carrier vehicles come out of the track entrance to the river and sure enough when we arrived at the river, there were the wet wheel tracks of these vehicles left behind on the steep entrance into the river, so we decided to go across, fording the river in the HiLux in H4, in four-wheel drive. I went first and kept a straight line across and the water was deeper over on the far side of the river and estimated to be just at wheel height. The second vehicle came across and then Matt took a different wider line and we could see water up to the bonnet before the front end of the vehicle reared up out of the water onto dry land. A sigh of relief went up from all watching!

The Mevelo River ford point with the damaged bridgeworks and sunken dislodged containers (looking north). (Photo courtesy David Billings.)

The Old Track

What we now know is that the former old track (part of which I have previously walked) which leads out of the Mevelo Valley and up to the Mumus and Yarras River Valleys, our planned route, is totally overgrown and cannot be used. It is a seven-hour 166 kilometer (106 miles) drive from Kokopo to Lamerien over very rough roads with what we thought were two major river crossings. We had three large rivers to cross, only one of which was bridged.

Change to the Planning

The crossing of the Mevelo River by the ford, which was forced upon us by the closure of the now “overgrown road” out of the Mevelo Valley meant that we had to rethink our carefully laid plans on several aspects: The Americans had appointments to keep on their return so had to get back for their flights. We got to the campsite on Thursday, June 7 and managed to get the tents up before dark. That left a maximum for them of six nights in the camp but in the light of the river fords (particularly the Mevelo River ford) we had to gauge intervals in the rain to get back over the Mevelo River, which was accessed as the biggest obstacle.

1. The American participants had a maximum of seven nights/six days at Wide Bay and had to return to Kokopo, the seventh day had been planned as the “return to Kokopo day.”

2. Originally it had been planned for two vehicles to return with the American participants and then one vehicle return to Wide Bay on the same day. It was now deemed too dangerous for one vehicle to make the trip back due possible breakdown on the rough roads or getting bogged on the mudslide. This planned return trip would take two days if carried out.

3. The drive cannot be done Kokopo to Wide Bay (Lamerien) and back in one day, it had been planned as a one-day trip because “if the river crossings were possible on that day in the morning” then they would still be able to be crossed later in the day. The two-day return trip negated that idea.

4. More importantly, we would have to ford the Mevelo River on a return journey and to that there was no alternative, the Mevelo River had to be crossed in order to get back to Kokopo with the vehicles, that meant the surety of a day when the river ford was at a low point.

5. We also had to make a contingency for the 100-meter-long mudslide in the road at roughly the halfway point, after the Sambei River, which doubtless would not have been repaired by the time of our return. This meant that lengths of logs had to be carried both for ballast in crossing the two main river fords and as fill to drop into the ruts on the mudslide section. The chainsaw also had to return with the vehicles in case of the need for more wood.

Secondary Jungle Visited Three Times

It rained the first night (Thursday) and Friday afternoon we made it up the hill. Since 2012 it has become just a tangled mess up there, the old bulldozer tracks are barely visible and the tree roots across the ground hold pools of water making it treacherous.

The climb up to the top of the hill can be quite steep in places and with the rain it was very slippery and some assistance was needed in paces and the willing hands of the young men of the village gave that assistance. The hill height is around 420 feet and the start level is 150 feet, so it is a tough climb over 270 feet of elevation.

David Billings in the East New Britain jungle checking search area location from previous GPS waypoints. (Photo courtesy David Billings.)

It rained the second night for three hours with lightning and thunder rolls and lashing rain from 12 p.m. to 3 a.m., and then more rain during that new day. June is supposed to be the “drier” month of the year. We went up the hill three times, it rained while we were in there.

Due to the available time for the Americans in the team, the rain, the rising rivers to cross and the vehicles to be got across the rivers, we had to consider getting out at an opportune time with the biggest obstacle, the Mevelo River, at a low point. We watched the Mevelo on a daily basis. The Mevelo went down a bit and we took the opportunity to get out on Monday, June 12. Seven hours later we were back in Kokopo.

“East New Britain Highway” is Atrocious

Back to the mudslide! Yes, the mudslide was still there and still about 100 meters long, but this time on the return, on an upslope. We had to remember that stretch for going back so we cut some logs the length of the HiLux tray and took two layers of 5-foot round logs back with us both as ballast for the river crossing and to patch up the road when we got to the mudslide. When we got there a big truck was bogged in, but luckily off to the side, so we gave them a shovel, then we filled in the deeper parts of one rut with the logs we carried and I went first with one wheel side in the rut and the other on the center “heap of slime,” and in H4 we all got through but it was close-run thing. All the villagers that were working on the road cheered! Most of the road is laterite where a bulldozer has shaved off the top soil and exposed the rock underneath but this section was just mud. The roads must be terrible on the HiLux suspension and most of the journey is in first and second gear with occasional third being used.

Members of David Billings’ team sweep the East New Britain jungle in search of the Earhart Electra. Once again, nothing was found on this, the seventeenth time he’s visited this remote area of the world in search of the lost plane. (Photo courtesy David Billings.)

Where do we go from here?

It is obvious that we cannot use vehicles again until the roads improve and bridges are built, that means use and reliance on a helicopter again, for “in” and “out,” with additional expense.

The idea was that by using vehicles we could cut down the expense and carry as much as we liked to make the camp comfortable. We had also intended to go down to the Ip River where a World War II wreck had been reported about 10 years ago and which no one has been to identify, so we had thought that we would do that, but the villagers told us that the coast track was impassable.

All the film taken will now be used to make a documentary concerning the search for the aircraft wreck seen in 1945, which I am convinced on the basis of the documentary evidence on the World War II map and the visual description by the Army veterans, is the elusive Electra. We shall have to wait and see what interest is generated by the documentary.

Sincerely,

David Billings,

Nambour,

Queensland, Australia (June 20, 2017)

Billings’ next trip to East New Britain will be his eighteenth, if he indeed makes it, and if persistence means anything at all, perhaps he will finally locate the wrecked airplane he believes was Amelia Earhart’s bird. I wish him the best of luck, as he will surely need it. If you’d like to contribute to his cause, you can visit his website, Earhart Lockheed Electra Search Project for details.

New Britain theory presents incredible possibilities

Like the recent Earhart timeline, this is another piece that’s long overdue. David Billings, a retired Australian aviation engineer, has worked intensely for over two decades on a project that, if successful, will turn nearly everything we assume about Amelia Earhart’s final flight on its head. I’ve known Billings casually through countless emails since about 2004, a year or so before his membership in the Amelia Earhart Society online discussion forum was revoked on a technicality by a hostile forum moderator.

Despite our vastly different beliefs about the Earhart disappearance, we’ve maintained a cordial communication. To me, Billings exemplifies the best in what some might consider the old-school Australian male, in that he’s forthright, with a sharp, wry sense of humor, unafraid to speak his mind, and dependably honest – a trait becoming increasingly rare in this day and age. His work is admirable and worthy of our attention.

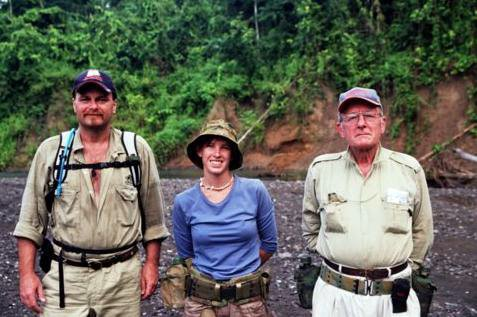

Chris Billings (David’s son), Claire Bowers (his step-daughter) and David Billings in the jungles of East New Britain, circa 2002.

The evidence that motivates Billings, 76, who works in relative obscurity out of his home in Nambour, Australia, where he often flies gliders to relax, is real and compelling. Unlike our better known, internationally acclaimed “Earhart experts,” whose transparently bogus claims are becoming increasingly indigestible as our duplicitous media continues to force-feed us their garbage, David is a serious researcher whose questions demand answers. His experience with our media is much like my own; with rare exceptions, his work has been ignored by our esteemed gatekeepers precisely because it’s based on real evidence that, if confirmed, would cause a great deal of discomfort to our Fourth Estate, or more accurately, our Fifth Column.

Rather than waste needless effort trying to describe Billings’ New Britain Theory in my own words, we will now turn to the home page of his comprehensive website, which provides a thorough introduction. The site, titled Earhart Lockheed Electra Search Project and subtitled “Earhart’s Disappearance Leads to New Britain: Second World War Australian Patrol Finds Tangible Evidence” presents a wealth of information in nine separate sections, is presented in a reader-friendly, professional style and is must reading for the serious Earhart student. We begin at the beginning; the following inset material is direct from the home page of the Earhart Lockheed Electra Search Project. (Boldface emphasis mine throughout.)

Of all the various theories and searches regarding the disappearance of Amelia Earhart, Fred Noonan, and their Lockheed Electra, only one endeavor has the tangible documentary evidence and eyewitness accounts to buttress the conclusion to their final resting place – the jungle floor in Papua New Guinea. In 1945, an Australian infantry unit discovered an unpainted all-metal twin-engine aircraft wreck in the jungle of East New Britain Island, in what was then called New Guinea.

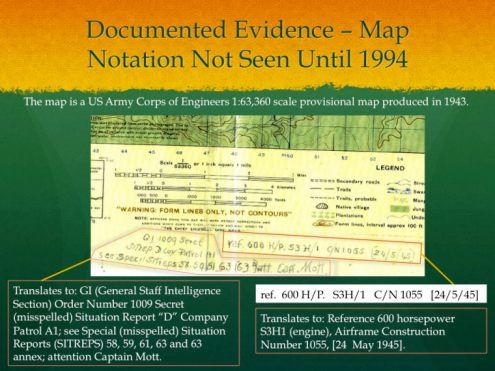

The Australian infantry patrol was unsure of their actual position in the jungle and were on site for only a few minutes. Before they left the site they retrieved a metal tag hanging by wire on an engine mount. The Australians reported their find and turned in the tag upon return to base. The tag has yet to be recovered from the maze of Australian and American archives, but the letters and numbers etched upon it were transcribed to a wartime map. The map, used by the same Australian unit, was rediscovered in the early 1990’s and revealed a notation “C/N 1055” and two other distinctive identifiers of Amelia Earhart’s Lockheed Electra Model 10E.

This map illustrates the Lae-to-Howland Island leg (green) that the Electra flew for about 20 hours. David Billings’ postulated return route (dotted red) to New Britain Island would have consumed the last bit of fuel and 12 more hours. Could this radical turn-around by Earhart have actually occurred, or is there another explanation for the existence of her Electra on New Britain Island? (Courtesy David Billings.)

On July 2, 1937, while en route to Howland Island from Lae, New Guinea, pilot Amelia Earhart and her navigator Fred Noonan disappeared shortly before they were to arrive at Howland Island – up to 2,600 miles and 20 hours after take-off. They were flying a modified Electra aircraft built specifically for the around-the-world journey. Had they arrived at Howland Island, their next stop would have been Hawaii, and finally California. A flight around the world would have been the first by a woman pilot. They undoubtedly encountered headwinds on the flight. The widely accepted last radio voice message from her was “. . . we are running on line north and south . . .” manually recorded 20 hours and 14 minutes after take-off by a United States Coast Guard ship at Howland.

This project theory holds that Earhart and Noonan, after flying some 19 hours should have “arrived” close to Howland, but after an hour of fruitless searching for the island, Amelia invoked the Contingency Plan she had made and turned back for the Gilbert Islands. While there were no known usable runways between Lae and Howland except for Rabaul, there was at least the opportunity to ditch the aircraft near to or crash-land on the numerous inhabited islands in the Gilberts along the way if needed, and there was more than sufficient range to reach Ocean or Nauru Islands. Earhart carefully husbanded the engines to extract the maximum range from the remaining fuel.

The aircraft had an advertised range of some 4,000 miles in calm air; there should have been plenty of fuel to retreat to the Gilberts at a minimum. Among the myriad of alleged radio calls from Earhart after her last confirmed message were four radio calls heard by the radio operator on Nauru Island . . . one call was heard just under two hours from her “final” transmission, and some 10 hours later, three more final calls on the pre-selected frequency were heard by the Nauru radioman. The Nauru radio operator was one of only a few radio operators who had reliably monitored Earhart on her outbound leg to Howland – he knew the sound of her voice over the radio. In any event, her aircraft has been projected to have run out of fuel some 50 miles south of Rabaul, New Britain Island, and then crash into the jungle.

The stunning evidence that suggests Amelia Earhart’s Electra was found in the Papua New Guinea jungle is in the area in yellow, above, which is the lower section of the tactical map maintained by “D” Company, 11th Australian Infantry Battalion in 1945. The Map was in possession of the unit’s administrative clerk from 1945 until 1993. (Courtesy David Billings.)

David Billings [sic], a now retired aircraft engineering professional, has been analyzing the flight and searching for Earhart’s Electra for more than 20 years in the jungle of East New Britain. Dense jungle, harsh terrain, poor maps, imprecise archival information, personal resource limitations, and possible natural or man-made burial of the wreckage, have thwarted success. He has led many expeditions into the search area, and has refined his analysis to the likely wreck site using terrain mobility studies, geospatial analysis of aerial and satellite images, custom-built maps, and re-analyzed archival maps and documents. As an example, the Australian-held wartime map is authentic, and the handwriting reflects unmistakable discreet data points and little known references of military operations in 1945 East New Britain.

The longtime map holder, the Second World War Infantry Unit clerk, Len Willoughby, retrieved the map from a map case on a pile of discarded equipment in 1945, and kept the map until he mailed it to former-Corporal Don Angwin in 1993 (and who revealed it to Mr. Billings in 1994). Neither of these former infantrymen had the motive nor “insider” expertise to create or introduce details concerning the Electra’s obscure component identification or situational nuances. The string of numbers and letters, “600 H/P. S3H/1 C/N1055,” remains the most significant historical notation found to date in the search for Earhart’s aircraft. This alpha-numeric sequence almost certainly mirrors the details on the metal tag recovered from the engine mount by one of the Australian soldiers on 17 April 1945. This three-group sequence translates to 600 Horsepower, Pratt & Whitney R-1340-S3H1, airframe Construction Number 1055. This airframe construction number IS Amelia Earhart’s Lockheed 10E Electra aircraft, and the engine type exactly matches as well. The eyewitness visual descriptions from three of the Australian veterans at the scene also strongly support this supposition. The date on the map, 24 May 1945, refers to the return answer to the Australians from the American Army, who did not believe it was “one of theirs.”

The foregoing should give you a fairly good snapshot of Billings’ New Britain Theory. Much more can be found in the pages of the Earhart Lockheed Electra Search Project.

In Fred Goerner’s 1966 bestseller, The Search for Amelia Earhart, the author recalled his first meeting with the famed Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, an interview arranged by Cmdr. John Pillsbury, public information officer for the 12th Naval District, in connection with Goerner’s work on a 1962 radio documentary The Silent Thunder.

A look at the East New Britain Island Mountains, where David Billings’ search for the possible wreckage of the Earhart Electra has been focused. (Courtesy David Billings.)

The meeting was the beginning of a friendship Goerner treasured, but it wasn’t until about a year later that Nimitz shared some of his inside knowledge about the Earhart case with Goerner. At Pillsbury’s retirement party at the Fort Mason Officers Club in San Francisco, he passed an incredible message to the KCBS newsman. “I’m officially retired now,” Pillsbury told Goerner, “so I’m going to tell you a couple of things. You’re on the right track with your Amelia Earhart investigation. Admiral Nimitz wants you to continue, and he says you’re onto something that will stagger your imagination. I’ll tell you this, too. You have the respect of a lot of people for the way you’ve stuck at this thing. Keep plugging. You’ll get the answers.” (Italics mine.)

Nimitz’s statement to Goerner through Pillsbury was a stunner, and it immediately found a permanent place in my memory when I read it for the first time so many years ago. Just what could the great Navy warrior have meant when he said, “You’re onto something that will stagger your imagination”? The answer has been elusive, but if Billings can locate the wreck, and it proves to be Earhart’s Electra, we’ll have a strong clue and a new place to start looking for that special something that Pillsbury hinted so strongly about.

In closing “Chapter II: The Final Flight” in Truth at Last, I cite some of the many questions that remain unanswered about those final hours: “What was Noonan, Pan Am’s best navigator, doing as their hopes of securing a safe landfall were evaporating before his eyes? Why the forty-minute void between Earhart’s 8:04 and 8:44 a.m. transmissions? Why couldn’t she hear Itasca on 3105 kc? Why did she ask for 7500 kc for bearings, when her direction finder could not home in on that frequency, instead of asking for 500 kc? Earhart never stayed on the air more than seven or eight seconds at a time, preventing the Itasca radiomen from taking bearings. Why? If the Electra was running out of fuel or experiencing another emergency, why didn’t she send a Mayday message?

“Did her transmitter break down after her last broadcast, as [Bill] Prymak suggested?” I continued. “Was she really trying to reach Howland, or was her peculiar behavior simply part of a deception to make it appear she was lost?” But one question never occurred to me: “Why was Amelia Earhart in a different Electra than the one she flew from Oakland, Calif., when she set off on her second world flight attempt on June 2, 1937?”

What would it mean if Billings finds the original Earhart Electra, NR 16020? First of all, the discovery should be, at minimum, the biggest story of the week worldwide, with virtually all media organizations in the West giving it top billing (no pun intended). If past is prologue, however, any news that reflects the truth in this longstanding cover-up will be universally ignored, though a few exceptions might occur with a story of this magnitude. Billings needs to find the wreck and identify it in a way that’s forensically conclusive.

Remember, the metal tag recovered from the engine mount has vanished, likely joining the Earhart briefcase discovered by Robert E. Wallack in a Japanese safe on 1944 Saipan, the photos of the fliers in Japanese custody that several GIs claimed they found but lost on Saipan, and whatever else might be squirreled away in top-secret hidey-holes. Assuming Billings is finally able to locate the wreck, how will he determine beyond doubt whether this is the long-lost Electra, and not just another World War II casualty?

“I have always been good at ‘aircraft recognition,’ seeing an aircraft and immediately recognizing the type of aircraft it is, particularly WWII military types,” Billings told me in an email. “After being with the Electra 10E for 20 years and looking at the pictures and three-view drawings, it would be easy to recognize from certain aspects; for instances: the look of the six window panels surrounding the cockpit and the twin tails, the cabin door, the fuel filler panels, the step in the setting of the horizontal stabilizer are all recognition features. We are, however, speaking here of a damaged Electra, from the sighting in 1945, said to be with the cockpit smashed back to the heavy main spar, so the cockpit with the DF loop on top is effectively ‘not there‘ and no description of the twin tails was given suggesting the empennage [tail assembly] is not there either.”

Billings says information he’s gleaned since 2011 indicates that the plane was purposely buried, though not too deeply, by someone using a bulldozer, so the use of metal detectors will be critical to a successful search. “When we get a strike with a metal detector then we follow the continuing strikes to map out the extent of what we have in the ground following the metal detector beeps,” Billings continued. “We mark a rough plan on the ground. From that, firstly I would then be looking away from the ground plan for a distance, for the left hand Engine Serial No. 6150, said to be 30 meters away from the airframe and it will be a lump on the ground, if the bulldozer driver missed seeing it. If we find that engine, then it will have a Pratt and Whitney Data Plate on the back of the blower housing with ‘6150’ stamped on it. At the airframe, if we have a rough ground plan we can dig where the right hand engine is as it too will have a Data plate showing ‘6149.’ One of these would be proof positive.”

An overview map of East New Britain, Papua New Guinea. Note location of Lae to the far left, bottom third. (U.S. Geological Survey map.)

Though I admire Billings’ work, we certainly don’t agree on everything. The idea that Earhart turned around and landed in the jungle of Papua New Guinea after nearly reaching Howland Island is unacceptable to me — and every other Earhart researcher I know. But the existence of the original Electra at East New Britain and the Marshalls-Saipan truth are not mutually exclusive, as would appear at first glance. Both can be true, and assuming Billings’ evidence isn’t some kind of bizarre hoax or misunderstanding, both must be true.

How can two scenarios that appear so radically different be part of a coherent series of events in the summer of 1937? One possible answer immediately suggests itself: Amelia Earhart changed planes somewhere along the line of her world flight route, and we already have some evidence to support the idea. Please see my earlier post, “The Case for the Earhart Miami Plane Change”: Another unique Rafford gift to Earhart saga for the entire confusing discussion. It’s not conclusive, of course, and it raises more questions than it answers.

The successful location and identification of the original Earhart Electra in East New Britain would be earth-shaking news, but it would also create a new Earhart “mystery,” a real one in this case, not the fabricated myth the establishment wants us to buy. If it’s ever discovered, the truth that explains the Electra’s presence in East New Britain could indeed “stagger our imagination.” In any event, a plane change and eventual crash of the original Electra in the East New Britain jungle under other circumstances makes far more sense to this observer than the dramatic turn-around Billings proposes. The Mili Atoll and Saipan evidence are just too overwhelming to support the entirety of Billings’ theory, in my view and that of others I respect.

An example of the dense jungle that covers the area where David Billings’ search for the Electra is focuses on Papua New Guinea. (Courtesy David Billings.)

Billings has made 16 trips to the Papua New Guinea jungle since 1994, and plans his final foray into East New Britain sometime in the spring of 2017, the 80th anniversary of Earhart’s disappearance. Funding is always a problem, but he says a recently completed road will allow vehicle access and eliminate the exorbitant helicopter costs previously incurred. Billings has always borne the heaviest part of the money burden, but if you’d like to help his cause, here’s a page with donation information.

In a recent email, I told Billings that I wanted to do a post about him and his work, writing, “We both want the truth, and if the original Electra is in the PNG jungle, so be it. IF and when you can prove it, we can then worry about how and why it got there!”

“Exactly!” he replied. “My same thoughts all along.”

New Mili search uncovers more potential evidence

Earhart researchers Dick Spink and Les Kinney, who led a search team sponsored by Parker Aerospace, returned from Mili Atoll in the Marshall Islands Jan. 30 after spending five days combing the tiny Endriken Islands near Barre Island with high-tech equipment including ground-penetrating radar and metal detectors.

Although no one has made any more claims that “concrete proof” or a “Holy Grail” has been found, the pair didn’t return empty-handed either, and some of the artifacts appear to have serious potential.

“Wow, what a trip!” Spink wrote in an email Feb. 3. “Two of the pieces we found are very consistent with what I found on my first couple expeditions to Mili. One piece in particular is some type of identification plate that is consistent in size with that of a Lockheed airframe tag. There is no way of knowing this until we get it to the lab, but you can tell it was some type of ID tag.

Dick Spink stands at what he believes is the spot where Amelia Earhart landed her Electra on July 2, 1937. Spink, Les Kinney and a search team returned to the area for a five-day search of the tiny Endriken Islands in late January.

“Something important to note,” Spink continued, “is that all of the aluminum pieces we found were in a direct line between where [I believe] the [Earhart] plane came to rest and the location of where the plane was loaded onto the shallow draft barge. Very interesting indeed, and the foundation of this story is becoming more solid.”

Readers unfamiliar with the full background on this story and the new search at Mili for parts of Amelia Earhart’s Electra can find details in my three earlier posts, Yahoo! News announces new search for Electra parts, “Recent find on Mili Atoll called “Concrete proof” and “Update to Recent find on Mili story.”

“We found six small artifacts that could or could not have come from the Electra,” Kinney wrote in a Jan. 29 email. “We also found a couple of small unidentified pieces of aluminum, and a round one inch diameter rusted magnet. Most of this stuff was buried — all except one piece were found by metal detectors.”

Kinney urged caution about making any premature announcements until thorough testing can be done. He will coordinate the tests, financed by Parker Aerospace and conducted as soon as possible. None of the tests will likely provide absolute proof that an artifact came from the Earhart plane, but Kinney, Spink and antique aircraft expert Jim Hayton all believe the aluminum plate and airwheel dust cover found by Spink in previous trips to the Endrikens were probably from the Electra.

Kinney also interviewed some native Marshallese he called “knowledgeable locals” in the Mili Atoll area, and says he “confirmed there were no aircraft wrecks on any of the nearby islands stretching out for at least ten miles” during or before the war years, with only one exception. This supports his earlier research, and makes the possibilities even stronger that one or more of the artifacts’ came from the Earhart plane.

“We also got some Japanese aircraft samples we picked up on Mili Island to compare the aluminum we got from our island,” Kinney wrote, adding that “everything has been cleared by the Marshallese government. I wrote up a release and the President signed it as well as the Historic Preservation Office Manager. Everything is legal.”

As has usually been the case when Earhart searches are undertaken by TIGHAR, Nauticos and others, the media has enthusiastically informed the public about the great adventure. These same news agencies have invariably failed to publish follow-ups when the searches fail to deliver. Much the same is the case here, though on a far smaller scale; nothing about the search has been published to date by Yahoo! News or any other media outlet, though Spink says he will be talking to a local newspaper soon, and other possible media exposure may be forthcoming.

Readers of this blog can be sure that this reporter will do all that he can to keep them informed about any news in what might be properly called “the postmodern” search for Amelia Earhart.

“No hard evidence” in Earhart case? Knaggs’ find on Mili refutes skeptics’ claim (First of two parts)

Even casual observers of the Earhart case know that the major weapon used by skeptics and critics of the truth, the blind crash-and-sankers, the Nikumaroro morons and the rest who refuse to accept the obvious about Amelia and Fred Noonan’s Mili Atoll landing and deaths on Saipan is their never-ending cry, “Where is the physical evidence? No hard evidence has even been found!” (Boldface emphasis mine throughout.)

Forget the many dozens of witness accounts from natives, Saipan veterans and other sources that so clearly points to the truth. Only when the Electra is finally discovered, they say, will the Earhart puzzle be solved. Until then, all theories are acceptable – except the hated Saipan truth, of course, which is little more than a “paranoid conspiracy theory,” far too “extremist” to have any validity. These bozos are quite happy to keep Amelia and Fred in cold storage for eternity, floating out there in the unfathomable ether where the world’s great mysteries abide.

Vincent V. Loomis at Mili, 1979. In four trips to the Marshall Islands, Loomis collected considerable witness testimony indicating the fliers’ presence there. His 1985 book, Amelia Earhart: The Final Story, is among the most important ever in establishing the presence of Amelia and Fred Noonan at Mili Atoll in the Marshall Islands on July 2, 1937.

They’re wrong, as usual. Hard evidence has been found and analyzed, and it tells us a compelling story. Most of the doubters are unaware of this evidence, but it makes little difference. Even if the Earhart plane was somehow miraculously found underneath the Saipan International Airport’s tarmac amid hundreds of tons of wartime refuse, where, as Thomas E. Devine has told us, the plane has been since it was bulldozed into a deep hole several months after it’s torching in the summer of 1944, the naysayers wouldn’t accept it. And our corrupt media, which has been so invested for so long in perpetuating the government’s big lie that Amelia’s fate remains a mystery, would take all pains to thoroughly ignore and suppress news of the discovery.

But that’s for another time. This post is the first of two that will present and discuss the hard evidence that was found at Mili Atoll, evidence that all but proves the reality of our heroes’ presence at Mili Atoll in July 1937. So that readers can best understand the sequence of events that led to the discovery of this artifact, a bit of background is in order.

Amelia Earhart: The Final Story among best ever penned

Former Air Force C-47 pilot Vincent V. Loomis and his wife, Georgette, traveled to the Marshalls in 1978 hoping to find the wreck of an unidentified plane Loomis saw on an uninhabited island near Ujae Atoll in 1952. Loomis never located the wreck, which he fervently dreamed was the lost Earhart plane, but in four trips to the Marshalls he obtained considerable witness testimony indicating the fliers’ presence there. Loomis’ 1985 book, Amelia Earhart: The Final Story, was praised by some at a time when big media’s rejection of information supporting Earhart’s survival and death on Saipan had yet to reach its virtual blackout of the past two decades, and is among the most important Earhart disappearance books ever written.

The Final Story’s most glowing review came from Jeffrey Hart, writing in William F. Buckley’s National Review. After gushing that Loomis “interviewed the surviving Japanese who were involved and he photographed the hitherto unknown Japanese military and diplomatic documents,” Hart flatly stated, “The mystery is a mystery no longer.” Of course, the U.S. government didn’t get Hart’s memo, and continued its abject silence on all things Earhart.

Two Marshallese fishermen, Jororo and Lijon, claimed that sometime before the war they saw an airplane land on the reef near Barre Island, about 200 feet offshore. “When ‘two men’ emerged from the machine, they produced a ‘yellow boat which grew,’ climbed aboard it and paddled for shore. “Jororo and Lijon, only teenagers, were frightened, crouching in the tiriki, the dense undergrowth, not quite knowing what to do,“ Vincent V. Loomis wrote. (Drawing courtesy of Doug Mills.)

On his first flight to Majuro, Loomis met Senator Amata Kabua and Tony DeBrum, commission officials seeking Marshallese independence from the United States. Kabua, a descendant of the first king of the Marshalls, Kabua the Great, said Earhart had come down in the islands and that her plane was still there. DeBrum told Loomis, “We all know about this woman who was reported to have come down on Mili southeast of Majuro, was captured by the Japanese and taken off to Jaluit. Remember, the stories were being told long before you Americans began asking questions.”

Among the witnesses Loomis interviewed at Mili Mili, the main island at Mili Atoll, was Mrs. Clement (Loomis provided no first name), the wife of the boat operator Loomis had hired. Mrs. Clement said her husband knew nothing, but she recalled that she had seen “this airplane and the woman pilot and the Japanese taking the woman and the man with her away.” She pointed out the area – “Over there … next to Barre Island” – as the spot where the plane had landed, but she offered no other information.

Loomis next sought out Jororo Alibar and Anibar Eine on Ejowa Island, hoping to confirm the story he heard from Ralph Middle on Majuro. Middle’s story was that two local fishermen, Jororo and Lijon, told him that before the war they saw an airplane land on the reef near Barre island, about 200 feet offshore. “When ‘two men’ emerged from the machine, they produced a ‘yellow boat which grew,’ climbed aboard it and paddled for shore,” Loomis wrote. “Jororo and Lijon, only teenagers, were frightened, crouching in the tiriki, the dense undergrowth, not quite knowing what to do.” Shortly after the men reached the island, the fishermen saw them bury a silver container, but the Japanese soon arrived and began to question, and then slap the two fliers, Middle said. When one screamed, Jororo and Lijon realized it was a woman. The pair continued to hide, watching in silence, because “they knew the Japanese would have killed them for what they had witnessed.”

The natives’ description of “the yellow boat which grew” is especially compelling for its realism, as it reflects their relatively primitive understanding of what only could have been an inflatable life boat produced by Earhart and Noonan after the Electra crash-landed, possibly on a reef. No inventory of the plane’s contents during the world flight is known to exist, but several sources support the common-sense idea that the fliers would not have departed Lae without such a vital piece of emergency equipment.

Amelia, My Courageous Sister, Muriel Earhart Morrissey and Carol L. Osborne’s 1987 biography, contains a photocopied story from the March 7, 1937 New York Herald Tribune, “Complete Navigation Room Ready to Guide Miss Earhart.” Discussing emergency items the Electra would carry on the first world flight, the unnamed reporter wrote, “In the fuselage will be a two-man rubber lifeboat, instantly inflatable from capsules of carbon dioxide.” In the July 20, 1937 search report of the Lexington Group commander, under “Probabilities Arising from Rumor or Reasonable Assumptions,” Number 3 states, “That the color of the lifeboat was yellow.”

In September 1979, South African writer Oliver Knaggs was hired by a film company to join Loomis in the Marshalls and chronicle his search. The Knaggs-Loomis connection is well known among Earhart buffs, but neither Loomis, in The Final Story, nor Knaggs, in his little-known 1983 book, Amelia Earhart: Her last flight (Howard Timmins, Cape Town, S.A), mentioned the other by name. In Her last flight, a collector’s item known mainly to researchers, Knaggs recounts his 1979 and ’81 investigations in the Marshalls and Saipan.

Knaggs wasn’t with Loomis when Ralph Middle told him about Lijon and Jororo at Majuro in 1979, and wasn’t there when Loomis interviewed Jororo. Knaggs wrote that “our leader [Loomis]” had told him of Lijon’s story, which he didn’t believe initially, but later, when a village elder repeated it, Knaggs became interested. Knaggs returned to Mili in 1981 without Loomis but armed with a metal detector in hopes of locating Lijon’s silver container, and establishing his own claim to fame in the search for Amelia Earhart.

In part two of this post, we’ll look at what Knaggs found, what the experts said about it and what it means in the continuing search for Amelia Earhart.

![Fishing boat story 5 This story appeared at the top of page 1 in the July 13, 1937 edition of the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania)-Globe Times. “Vague and unconfirmed rumors that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan have been rescued by a Japanese fishing boat without a radio,” the report began, “and therefore unable to make any report, found no verification here today, but plunged Tokio [sic] into a fever of excitement.” The story was quickly squelched in Japan, and no follow-up was done. (Courtesy Woody Peard.)](https://i0.wp.com/earharttruth.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/fishing-boat-story-5.png?w=616&h=352&ssl=1)

Recent Comments