AES’s Cam Warren on “Noonan & Earhart”

Cameron A. “Cam” Warren, former longtime member of the Amelia Earhart Society, may be still with us and in his upper 90s in Fountain Hills, Ariz., but my information on his current status remains nil. Warren was among the best known of the few “crashed-and-sankers” in the AES, along with former ONI agent Ron Bright and Gary LaPook, who are both alive and well, to my knowledge.

Warren’s “Noonan and Earhart” appeared in the October 1999 edition of the Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters. It’s a good general summary of the nuts and bolts of the Earhart story, something you don’t see often, and good to use occasionally as a reference. Opinions expressed in this piece are those of the Cam Warren and do not necessarily reflect those of the editor or anyone else. Boldface emphasis mine throughout.

“Noonan & Earhart”

by Cam Warren

What exactly was the relationship between Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan? Originally Amelia was going to fly around the earth solo, at least if her husband, George Putnam, had his way. And his way was to revive a fading star, turn her into the World’s Most Famous Woman, and live comfortably ever after on book royalties, endorsements and the other fruits of international fame.

Accounts and interpretations vary, and curiously enough the true relationship of the Putnams has been well glossed over by most biographers. There is little doubt of Amelia’s accomplishments both in aviation and in the field of what we now know as the feminist movement. We have been told of the love that presumably existed between George and Amelia, but the latter herself showed some doubt as to how well the marriage would work out. And there is more than a little suspicion that George was very much the Svengali, manipulating Amelia to his own purposes. Perhaps, but she had her own ambitions too, and probably didn’t require a great deal of persuading to set forth on the next big adventure — a solo flight around the world.

This photo appeared in the October 1999 issue of the Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters with the tagline, “Amelia at Wheeler Field, Hawaii 1935.” Courtesy of Col. Rollin Reineck.

When Putnam & Company got into the serious planning for the ambitious undertaking, it didn’t take long for them to realize that the long over-water portions would require some help in the form of a skilled navigator. (Apparently a co-pilot wasn’t considered — this was to be an Earhart showcase.) So Amelia would have the services of Harry Manning, an accomplished sea captain, skilled in navigation and radio operation. He would accompany Amelia as far as Australia, shepherding her over the vast Pacific. Since Howland Island, the first stop after Hawaii, was such a small target, it was further decided to obtain the services of ex-Pan American Airways navigator Fred Noonan, an acknowledged expert on trans-Pacific flying.

Noonan’s credentials included Pan Am survey flights, and the first commercial seaplane operations in the Pacific. There have been hints he was relieved of his Pan Am position as the result of a drinking problem, although precise confirmation of this has not surfaced. Suffice to say, he was available and, despite having just been married, was willing to accept the risks of the flight. It has been said he planned to open a school for aviation navigators after his stint with Amelia; undoubtedly, he felt the attendant publicity would be useful.

But to avoid any upstaging of Amelia, Noonan’s contribution would be relatively small — he would accompany her to Honolulu, and then to Howland, where he would disembark and catch a ride back to Hawaii on a Coast Guard cutter. But plans had to be revised when Earhart cracked up her Electra on takeoff from Hawaii’s Luke Field. Manning, saying his leave of absence from the cruise line for which he normally worked was about to expire, bowed out when Amelia spoke of a “retry.” Privately Manning expressed great relief at surviving the accident and did not wish to press his luck further.

Amelia Earhart with Harry Manning (center) and Fred Noonan, in Hawaii just before the Luke Field crash that sent Manning back to England and left Noonan as the sole navigator for the world flight.

Noonan agreed to stay on, even after Putnam explained his role would be expanded to the full circumnavigation — this time starting eastward. One suspects it was made clear that Amelia would be the star; Noonan’s role was to be minor — he would be merely a hired hand. A proud and capable man, Fred was still a good soldier, and knew all about performing a subordinate role on a team. AE would be the boss — no doubt about it — and Fred would carry out her orders without question. Mindful of his less than strong bargaining position, he accepted the terms.

A word about teams, especially the two-party type. Successful ones depend heavily on inter-personal relationships; the pair must fit together like Yin and Yang. Abilities must be respected, but an occasional misstep must be accepted without rancor, in the full knowledge that the mistake was not an intentional one. Most commonly, the experienced know that A’s error will most assuredly be matched, sooner or later, by B’s. Any tendency to flare up by one of the parties is extremely serious, and quickly becomes the “burr under the saddle.” A famous recent example being a young couple, very much in love, who undertook to row to Australia together. They eventually made it, but never spoke to each other again.

It’s highly likely that friction developed within the Electra, and a safe bet that of the two, Fred was the more restrained. Obviously, the success of the mission largely depended on a comfortable rapport between them. Quite likely, under the stress and strain of the long hops, patience wore thin, and the chances are good that when operational questions arose, Amelia did it her way. Perhaps this could be excused; she was very proud of her flying ability and justifiably so, but “seat of the pants” judgments are risky. Noonan would go by the book, but would no doubt accept her decision if need be.

Earhart was impressed by Fred’s navigational wizardry, although her self-confidence apparently led her astray as they approached Dakar, on the African west coast. She overrode Fred’s advice and turned left to St. Louis, a couple of hundred miles to the north. This has been explained as intentional by some researchers, but Amelia sounded contrite about her move in Last Flight, the book put together from her in-flight notes by ghost-writer Janet Mabie, and hastily published by Putnam. The book seems to indicate Fred rode up front, at least during the early days, but moved back into the navigator’s “office” as time went on and the atmosphere grew chilly.

If my analysis of the situation is correct, several puzzling facts in the story of the Electra’s disappearance are explained. Firstly, why was Noonan never heard on the radio? Certainly, common sense would dictate his sitting up in the co-pilot’s seat as they looked for Howland Island. A second pair of eyes would help Earhart’s visual search, and Fred could easily man the radio. But such does not appear to have been the case; Fred had his charts and his navigation gear and a convenient table back aft, and most likely Amelia thought he should remain back there calculating their position.

Researcher Joe Gervais interviewed Jim Collopy at his home in Melbourne, Australia in 1962. Collopy, the former regional aviation administrator at Lae, told of joining Noonan for a drink before dinner the evening following the Electra’s arrival in New Guinea. He described a confidence Fred privately shared about his employer. After describing Amelia in a less-than-complimentary, fashion, Noonan added “she can fly and I can navigate and let’s leave it at that!” Incidentally, although he may have been sorely tempted under the circumstances, Fred did not do any heavy drinking the night before takeoff, as some reports have stated.

Fred certainly knew the value of radio communications; Amelia treated the facilities in a cavalier fashion. This can partly be traced to previous flights, when eavesdropping listeners were plotting the Electra’s progress to the annoyance of Putnam and the newspapers to which he had promised “exclusive” coverage. “Keep your messages as brief as possible” he likely warned her, “and don’t give away anything over the radio.” How else to explain her on-the-air reticence; the terse broadcasts only on a set schedule?

Another look at the original flight plan that targeted Howland Island, the “line of position” of 157-337 Amelia reported in her final message, and the close proximity of Baker Island, just southeast of Howland, as well as the Phoenix Group, farther to the southeast. which includes Canton Island, as well as Nikumaroro, formerly known as Gardner Island, of popular renown.

As they approached Howland, Earhart was heard to say, “We must be on you, but cannot see you,” referring to the waiting Coast Guard cutter Itasca. Then “we are circling but cannot hear you — go ahead on 7500 [kc]” [an unsuccessful attempt to get a direction finder fix]. This offers us a clue as to her mind-set. “Circling” was what an old barnstormer would do, while looking for a landing place, or trying to spot a ship. A highly unlikely maneuver for Noonan to suggest — search patterns are invariably flown in a precise rectangular pattern that can be plotted. Circling, on the other hand, is an imprecise maneuver.

When Howland did not appear, and a search was not bearing any fruit, Noonan would certainly suggest a heading for the nearest land, and land of sufficient size to be easily spotted. His choice most likely would have been to the southeast, toward Baker and the Phoenix Islands. Had they headed in that direction, they would have emerged from the cloud bank they undoubtedly were in. Then they might have spotted the Itasca, which was making black smoke, or at least Fred could have worked out a position based on the now-visible sun.

Earhart allegedly told friends that if she couldn’t find Howland, she would reverse course and “head back to the Gilberts.” Again, most likely a choice not enthusiastically supported by Fred. Many researchers feel they were much further north than believed, and somehow reached the Marshall Islands instead. No one knows just how close to Howland they really were — there is conflicting evidence — but the nearest land to the west or northwest was a long distance away, and even with her gasoline reserve, probably unreachable.

The Coast Guard, the Navy, and most experts are sure the Electra splashed down hard and went to the bottom. A few optimists postulate Earhart made a successful water landing, and the plane floated for a time. If so, perhaps the crew WAS rescued by a Japanese ship, although none has ever been positively placed in the vicinity. No matter, the ending may well have been a success story, despite the ill-luck with the weather and the malfunctioning, or the mishandling, of the radio and direction finder, if only the crew had been able to work together more smoothly.

No hard evidence supports this scenario, so we cannot claim to have “solved the mystery.” However, it certainly is credible, and a thoughtful analysis of the personalities involved offers considerable substantiation. Even Putnam’s post-loss behavior tells us something, for he lost no time in having his wife declared legally dead within months, and quickly took a new bride. Hardly the behavior of a devoted husband, grieving over his true love. Of Amelia and Fred, my deepest sympathies go to the latter; to a talented and capable man thrust into a life-threatening situation, saddled with an ambitious and overconfident pilot. Fred undoubtedly never faltered in his assignment, and most likely died with a slide-rule in his hand.

For more on Cam Warren’s work, please see my Feb. 1, 2019 post, “Fred Hooven: ‘Man Who (Nearly) Found Earhart.‘ ”

84th anniversary of Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight

July is Amelia Earhart’s month, for those of us who still honor the memory of this great American, and we don’t forget Fred Noonan, Amelia’s intrepid navigator whose sad destiny was inextricably bound to her own.

July 2 is the 84th anniversary of Earhart and Noonan’s fateful takeoff from Lae, New Guinea in 1937, officially bound for Howland Island, 2,556 miles distant, a tiny speck in the Pacific, never flown before and the most difficult leg of their world-flight attempt. What happened that compelled the fliers to land their Electra 10E off Barre Island at Mili Atoll, about 850 miles to the north-northwest, twenty-some hours later, remains the true mystery in the Earhart disappearance. All else is smoke, mirrors and endless lies.

Guinea Airways employee Alan Board is credited with this photo of the Electra just before leaving the ground on its takeoff from Lae, New Guinea on the morning of July 2, 1937. This is the last known photo of the Earhart Electra.

No missing-persons case has ever been as misreported and misunderstood. As I’ve said and written countless times, the widely accepted canard that the Earhart disappearance remains among the 20th century’s “greatest mysteries” is a vile, abject lie, the result of eight decades of government-media propaganda aimed at perpetuating public ignorance about the fliers’ wretched ends at the hands of the pre-war Japanese military on Saipan. Considering the lengths to which the U.S. government has gone to obscure, cover-up and deny the truth, it appears this state of affairs will persist until the Last Day. At that time, many will have much to answer for.

To review some of the anniversary articles posted here in past Julys, please see my 77th anniversary post of June 24, 2014; “July 2, ’17: 80 years of lies in the Earhart ‘Mystery’ ”; or last year’s story, “July 2020: Earhart forgotten amid nation’s chaos.”

As for any Earhart news, this year is among the quietest in memory — virtually nothing is happening, at least to my knowledge. A pair of pathetic cranks are claiming they’ve found the Earhart plane just off Nikumaroro and have even started a website with strange, inscrutable photos and nonsensical gibberish.

View of group posed in front of Amelia Earhart’s Lockheed Model 10-E Electra (NR 16020) at Lae, New Guinea, July 1937. Second and fourth from left are identified as Mr. and Mrs. Joubert (manager of Bulolo Gold Dredging and his wife), while Mrs. Chater (wife of the Manager of Guinea Airways) is seen third from left. Amelia Earhart can be seen third from right, and Fred Noonan is at far right.

No one in the mainstream media — or anywhere else — has paid a gnat’s worth of attention to the latest crap, and I won’t dignify this absurd, backhanded swipe at TIGHAR’s 30-plus years of propagandizing and fruitless searching off and on Nikumaroro by linking it here. You certainly don’t need to know about it, but if you insist, you can search under “Road to Amelia Earhart” and you’ll find it unless it’s already been circular filed under “lies no one will believe.” I only mention it because things are so currently comatose in Earhartland, and this latest is more proof that nature abhors a vacuum.

The below cartoon from the Kansas City Star goes back to early 1994, but its misplaced humor perfectly captures the zeitgeist that’s always defined the Earhart matter. Far from being one of history’s “most perplexing questions,” as an angel explains to a newly arrived soul, the truth about the loss of Amelia Earhart is well-known and one of the most precious sacred cows in the corrupt archives of the U.S. national security apparatus.

On a rare positive note, Polish author and publisher Sławomir M. Kozak recently informed me about his forthcoming book, Requiem for Amelia Earhart, which will introduce the Polish people to the truth about the Earhart disappearance. Requiem is scheduled for publication on Sept. 11, 2021, the 20th anniversary of possibly America’s greatest betrayal, another sacred cow whose truth has eluded as many Americans as the Earhart cover-up, and another subject that the erudite Slawomir has studied closely. His website is www.oficyna-aurora.pl.

On July 24, Marie Castro and the Amelia Earhart Memorial Monument Inc. (AEMMI) will get together on Saipan to celebrate Amelia’s 124th Birthday, and I’ll have photos and comments when that time rolls around.

In ’85 letter, eyewitness describes Earhart’s takeoff, Insists Noonan “had no drink” before last flight

Bob Iredale, Socony-Vacuum Corp. manager at Lae, New Guinea, spent two days with Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan before the last leg of their world flight attempt in early July 1937. In this 1985 missive, he offers Fred Goerner a firsthand account of their last takeoff, plus his opinion about what happened later. The following letter appeared in the November 1998 issue of Bill Prymak’s Amelia Earhart Society Newsletters. Boldface emphasis mine throughout.

793 Esplanade

Mornington

Victoria Aust. 3931

July 28, 1985

Dear Mr. Goerner,

Through good work by Australia Post, I received your letter 15 days after your post date of July 11. I am glad to be able to assist your research about Amelia Earhart, as I have read many views by writers, example, spying for the U.S. against Japanese in the Marianas, beheaded by the Japs, still alive in the U.S., etc., etc., all of which to me is a lot of sensationalist garbage.

C.K. Gamble was president of the Vacuum Oil Co., a subsidiary of U.S. Standard Vacuum, when he was a young man. Fred Haig, our Aviation officer, and I knew him quite well, then and later. Up until a year ago I chatted to him about Amelia many times and he recorded the views I’ll relate to you. Fred left the Planet over 12 months ago, hence no response to your letters. He was in his 80s.

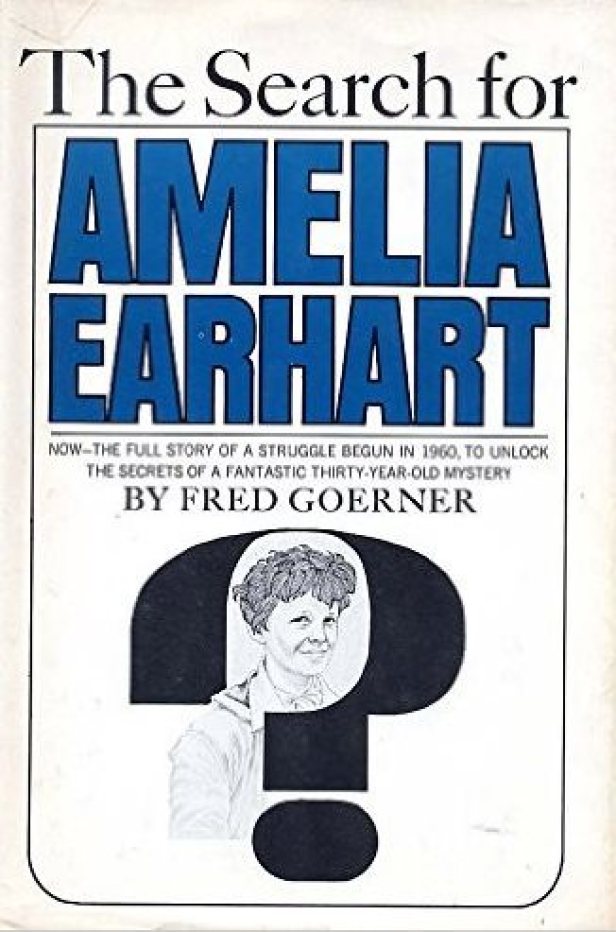

KCBS newsman and bestselling author Fred Goerner, right, with the talk show host Art Linkletter, circa 1966, shortly before the establishment media, beginning with Time magazine, turned on Goerner and panned his great book, The Search for Amelia Earhart, telling readers, in essence, “Move along, Sheeple, nothing to see here.”

Yes, I fueled the Lockheed and did it personally. Fred had arranged 20 x 44 gallon drums of Avgas 80 octane shipped out to us from California many months before. I can assure you all tanks were absolutely full — the wing tanks and those inside the fuselage. After she had done a test flight, I topped them up again before her final take-off. I think she took somewhere around 800 gallons all up. Fred Noonan was with me at the fueling and checked it out. He was also with me when we changed the engine oil, as was Amelia. I enclose a much faded photo, me in white, Fred in brown, and Amelia leaning on the trailing edge of the wing. [Photo not available.]

You are aware that because of an unfavorable weather forecast from Darwin (some 700 miles SW of Lae), of at least 2 days, Amelia decided on a two-day layover at Lae. She stayed with Eric Chater, General Manager of Guinea Airways, and Fred with Frank Howard and myself at Voco House. Frank and I shared quite a large bungalow as the two representatives of Vacuum Oil in N.G. He died, unfortunately, in 1962. As was our custom, we had a drink in the evening — 90 degrees F, and 95 percent humidity made it that way.

We asked Fred if he would join us the first night, and his comment was, “I’ve been 3 parts around the world without a drink and now we are here for a couple of days, I’ll have one. Have you a Vat 69?” I did happen to have one so the three of us knocked it off. He confessed to Amelia next morning he had a bit of a head, and her comment was, “Naughty boy, Freddie.” That was the only drink session we had, and to suggest he was inebriated before they took off is mischievous nonsense. I can assure you or anyone he had no drink for at least 24 hours before take-off.

We talked a lot about his experience as a Captain on the China Clippers flying from the West Coast to China, and he told us of his expertise in Astro-navigation, amongst other things. We all talked about ourselves, and he showed great interest in our life at Lae. He came around our little depot, where we stored drums of petrol, oil, and kerosene in the jungle to keep the sun off, etc. He told us how keen Amelia was to write a book about the flight, and the different people.

In the two days at Lae, she tried to learn pidgin English and talk to the [natives], and about her ability wherever they landed to take the cowls off the engines and do a Daily Inspection. A remarkable woman, and he has great admiration for her ability. He spent a lot of time with me in Guinea Airways hanger, and around the airfield, looking at the JU31’s, the tri-motored metal Junkers planes that flew our produce and the dredge up to Bulolo, how they were loaded with cranes and all that.

Guinea Airways employee Alan Board is credited with this photo of the Electra just before leaving the ground on its takeoff from Lae, New Guinea on the morning of July 2, 1937. This is the last known photo of the Earhart Electra.

Their final take-off was something to see. We had a grass strip some 900/1000 yards long, one end the jungle, the other the sea. Amelia tucked the tail of the plane almost into the jungle, brakes on, engines full bore, and let go. They were still on the ground at the end of the strip. It took off, lowered toward the water some 30 feet below, and the props made ripples on the water. Gradually they gained height, and some 15 miles out, I guess they may have been at 200 feet. The radio operator at Guinea Airways kept contact by Morse for about 1,000 miles where they were on course at 10,000 feet, and got out of range.

In 1940, I joined the Australian Air Force as a pilot, trained in Canada, and operated in England with the RAF before being promoted to a Wing Commander, commanding an Australian Mosquito Squadron attached to the 2nd Tactical Air Force. I did 70 missions in all sorts of weather, awarded Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar, French Croix de Guerre with Palm for blowing up a prison in France, and other operations for the French. I mention this only as that experience confirmed what I believe happened to Amelia. It is just another view.

The possibility is that they ran into bad weather, 10/10th cloud up to 30,000 feet at the equator, which negated Fred’s ability of Astro-navigation; he would have relied on DR navigation where wind can put you 50 miles off course, cloud base too low to get below it because the altimeter is all to hell if you do not know the barometric pressure, and to see a searchlight provided by a U.S. Cruiser under those circumstances would be impossible. My guess is they got to where Howland Island should have been in the dark, spent an hour looking for it, before having to ditch somewhere within a 50 mile radius of Howland. I find it hard to accept anything else.

Group posed in front of Amelia Earhart’s Lockheed Model 10-E Electra (NR 16020) at Lae, New Guinea, July 1937. From left are Eric Chater (manager, Guinea Airways), Mrs. Chater, Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan.

I hope I have not bored you. If I can provide anything at all beyond these comments, do write. As long as I am above ground, I’ll reply.

Sincerely,

Bob Iredale

P.S. Can I get your first book in Australia?

Doubtless Iredale could have obtained The Search for Amelia Earhart, Goerner’s only book, in Australia, though the shipping and handling charges might have been a bit stiff. He certainly needed to read it closely, considering his closing statement, “My guess is they got to where Howland Island should have been in the dark, spent an hour looking for it, before having to ditch somewhere within a 50 mile radius of Howland. I find it hard to accept anything else.”

Perhaps Iredale’s most important contribution in this letter is his up-close-and-personal account of drinking Vat 69 with Fred Noonan two nights before the doomed fliers took off, and his assurance to Goerner, that “he had no drink for at least 24 hours before take-off.”

For an extensive examination of the always-controversial issue of Noonan’s drinking, please see my Jan. 6, 2015 post, “Fred Noonan’s drinking: In search of the true story.”

I don’t believe I have Goerner’s reply to Iredale, but if anyone out there does, please let me know and I’ll be glad to post it.

Earhart’s “Disappearing Footprints,” Part III

Today we move along to Part III of Capt. Calvin Pitts’ “Amelia Earhart: DISAPPEARING FOOTPRINTS IN THE SKY,” his studied analysis of Amelia Earhart’s final flight. We left Part II with Calvin’s description of the communication failures between the Navy tug USS Ontario and the ill-fated fliers.

“What neither of them knew at that time was the agonizing fact that the Electra was not equipped for low-frequency broadcast,” Calvin wrote, “and the Ontario was not equipped for high-frequency. . . . After changing frequencies to one that the Ontario could not receive, it is safe to assume that Amelia made several voice calls. Morse code, of course, was already out of the picture.”

We’re honored that Calvin has so embraced the truth in the Earhart disappearance that he’s spent countless hours working to explain the apparently inexplicable — how and why Amelia Earhart reached and landed at Mili Atoll on July 2, 1937. Here’s Part III, with even more to follow.

“Amelia Earhart: DISAPPEARING FOOTPRINTS IN THE SKY, Part III”

By Capt. Calvin Pitts

Although Amelia was obviously trying to make contact with the Ontario by radio, Lt. Blakeslee did not know that. By the same token, Amelia had to wonder why he would not answer.

USS Ontario (AT-13), was a Navy tug servicing the Samoa area, but assigned to the Earhart flight twice as a mid-point weather and radio station for assistance.

This failure to communicate, however, worked into Amelia’s new plan. Since she had no way of letting the Ontario know they were en route, being without Morse code and having frequencies which were not compatible, now that he had been plying those waters for 10 days along her flight path, she knew it was useless to try to find and to overfly the unknown position of the Ontario in the thick darkness of a Pacific night.

Therefore, it now made even more sense to continue on to Nauru whose people had been alerted by Balfour that the Electra was probably coming. Although that had begun as a suggestion, no one yet knew that it had now become a decision. She needed to let the Ontario know — but how?

She had lost contact with Balfour, couldn’t make contact with the Ontario, and the Itasca had not yet entered the picture. Nauru, it was later learned, had a similar problem as the Ontario, and Tarawa had not broadcast anything. Amelia was good at making last-minute decisions. “Let’s press on to Nauru,” she might have said. “It’s a small diversion, and a great gain in getting a solid land-fix. I’ll explain later.”

The local chief of Nauru Island, or someone in authority, already had a long string of powerful spot lights set up for local mining purposes. He would turn them on with such brightness, 5,000 candlepower, that they could be seen for more than 34 miles at sea level, even more at altitude.

Finding a well-lit island was a sure thing. Finding a small ship in the dark ocean, which had no ETA for them, was doubtful. Further, as was later learned from the Ontario logs, the winds from the E-NE were blowing cumulus clouds into their area, which, by 1:00 a.m. were overcast with rain squalls. It is possible that earlier, a darkening sky to the east would have been further assurance that deviating slightly over Nauru was the right decision.

As the Electra approached the dark island now lit with bright lights, Nauru radio received a message at 10:36 p.m. from Amelia that said, “We see a ship (lights) ahead.”

Others have interpreted this as evidence that Amelia was still on course for the Ontario, and was saying that she had seen its lights. The conflict here is that Amelia flew close enough to Nauru for ground observers to state they had heard and seen the plane. How could Amelia see Nauru at the same time she saw the Ontario more than 100 miles away?

Amelia may have wondered if Noonan and Balfour were wrong about Nauru. But they weren’t. According to the log from a different ship coming from New Zealand south of them, they were en route to Nauru for mining business. Those shipmates of the MV Myrtlebank, a 5,150 ton freighter owned by a large shipping conglomerate, under the British flag, recorded their position as southwest of Nauru at about 10:30 pm on that date. The story of the Mrytlebank fits in well to resolve this confusion. It was undoubtedly this New Zealand ship, not the Ontario, that Amelia had seen.

Those shipmates of the MV Myrtlebank, a 5,150 ton freighter owned by a large shipping conglomerate, under the British flag, recorded their position as southwest of Nauru at about 10:30 pm on that date. The story of the Mrytlebank fits in well to resolve this confusion. It was undoubtedly this New Zealand ship, not the Ontario, that Amelia had seen.

MV Myrtlebank, a freighter owned by Bank Line Ltd., was chartered to a British Phosphate Commission at Nauru. As recorded later, around 10:30 p.m., third mate Syd Dowdeswell was “surprised to hear the sound of an aircraft approaching and lasting about a minute. He reported the incident to the captain who received it ‘with some skepticism’ because aircraft were virtually unknown in that part of the Pacific at that time. Neither Dowdeswell nor the captain knew about Earhart’s flight.”

Source: State Department telegram from Sydney, Australia dated July 3, 1937: “Amalgamated Wireless state information received that report from ‘Nauru’ was sent to Bolinas Radio ‘at . . . 6.54 PM Sydney time today on (6210 kHz), fairly strong signals, speech not intelligible, no hum of plane in background but voice similar that emitted from plane in flight last night between 4.30 and 9.30 P.M.’ Message from plane when at least 60 miles south of Nauru received 8.30 p.m., Sydney time, July 2 saying ‘A ship in sight ahead.’ Since identified as steamer Myrtle Bank (sic) which arrived Nauru daybreak today.”

“Unless Mr. T.H. Cude produced the actual radio log for that night, the contemporary written record (the State Dept. telegram) trumps his 20-plus-year-old recollection.”

The MV MYRTLEBANK of the BANK LINE Limited was about 60 nautical miles southwest of Nauru Island when it entered the pages of history. Amelia Earhart said, “See ship (lights) ahead.” This was most likely that ship since the Ontario would have been 80 to 100 miles away. Nauru, the destination of this ship, was lit with powerful mining lights. At Nauru Island, the Electra would be eight-plus hours from “Area 13,” or 2013z (8:43 am) 150-plus miles from Howland Island.

This was most likely the ship about which Amelia Earhart said: “See ship (lights) ahead.” Most researchers state that she had spotted the USS Ontario, which had been ordered by the Navy to be stationed halfway between Lae and Howland for weather information via radio. No radio contact was ever made between Amelia’s Lockheed Electra 10E and the Ontario.

While it is possible that Amelia flew only close enough to Nauru to see the bright mining lights, it is more likely that a navigator like Noonan would want a firm land fix on time and exact location.

For this reason, in a re-creation of the flight path on Google Earth, which we have done, we posit the belief, in view of the silence from the Ontario, that having a known fix prior to heading out into the dark waters, overcast skies and rain squalls of the last half of the 2,556-mile (now 2,650-mile) trip to small Howland, it was the better part of wisdom to overfly Nauru.

Weather and radio issues were the motive behind Harry Balfour’s suggestion to use Nauru as an intermediate point rather than a small ship in a dark ocean. Thus, the Myrtlebank unwittingly became part of the history of a great world event.

Now, with the land mass of Nauru under them, Fred could begin the next eight hours from a known position. Balfour’s suggestion and Fred and Amelia’s decision was not a bad call, with apologies to the crew of the Ontario. Unfortunately, it was not until after the fact that the Ontario was notified of this. They headed back to Samoa with barely enough coal to make it home. Lt. Blakeslee said they were “scraping the bottom” for coal by the time they returned.

The details of the eight-hour flight from Nauru are contained in the Itasca log. In my own case, the Amelia story was interesting, but not compelling. However, it was not until I began to study in minute detail the Itasca logs of those last hours of the Electra’s flight, hour by hour, and visualizing it by means of Google Earth, that the interest turned to a passion.

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED? DO WE HAVE ENOUGH EVIDENCE TO KNOW? IS THERE REALLY NO ANSWER TO WHAT HAS BEEN CONCEALED AS A “MYSTERY”?

In the reliving of what was once a mystery, things began to make sense, piece by piece. It was like being a detective who knew there were hidden pieces, but what were they, and where did they fit? For me, as the puzzle began to come together, the interest grew. There is really more to this story, much more, than appeared during the first reading.

Itasca Chief Radioman Leo Bellarts and three other Coast Guard radiomen worked in vain to bring Amelia Earhart, Fred Noonan and the Electra to a safe landing at Howland Island. Photo courtesy Dave Bellarts.

The radio room positions and pages being logged contained valuable information. Reading the details created a picture in the imagination at one level, but with more and more evidence piling up, a different level began to emerge.

Can this story really be true? Credulity was giving way to the reality of evidence.

If you will follow the highlights of the Itasca logs, you may find yourself captivated, as I was. One thing that is not spoken at first, but becomes a message loud and clear, is the not-so-hidden narrative in those repeated, unanswered Morse code transmissions.

The radiomen thought they were helping Amelia and Fred, but with each unanswered Code message, they were really just talking to themselves. As they get more desperate, you keep wondering: Surely the Electra crew can at least “hear” the clicks and clacks, the dits and dahs, even if they don’t fully understand them.

Why don’t they at least acknowledge they hear even though understanding appears to be absent? Why the silence, the long silence into the dark night, the silence which leaves the Itasca crew bewildered, even “screaming,” as they later said, “into the mike?”

The Coast Guard Cutter Itasca was anchored off Howland Island on July 2, 1937 to help Amelia Earhart find the island and land safely at the airstrip that had been prepared there for her Lockheed Electra 10E.

The position of the Electra, an “area,” not a fix, is our primary destination now because Howland was never seen. This makes Howland secondary for this exercise, mostly because that was not the position from which Amelia made her final and fatal decision.

There were at least two extremely dangerous elements involving Howland, and one strategic matter. Dangerous: 10,000 nesting and flying birds waiting to greet Mama big bird, and the extremely limited landing area of a 30 city-block by 10-block sand mass.

We delay our discussion about “strategic” since it deals with the government hijacking of a civilian plane, something controversial but which is worth waiting for. Stand by.

For now, we join Amelia and Fred for some details of their flight to “Area 13.” The purpose here is to locate, as best we can, that area from which Amelia made her final navigation decision.

That area encompasses a portion of ocean 200 miles by 200 miles. South to north, it begins about 100 miles north of Howland to at least 300 miles north. East to west, it begins with a NW line of 337 degrees and continues west parallel to that line for at least 200 miles.

There is a mountain of calculation behind that conclusion, but those details are for another venue. For now, for those interested in re-creating that historic flight, especially if you have Google Earth, follow the Itasca log in order to see Google Truth.

We designate this 200 by 200 miles as “Area 13” for the simple reason that their last known transmission not within sight of land which can be confirmed was at 2013z (GMT) (the famous 8:43 am call). Following this was nothing but silence for those on the ground.

After their long night of calling, waiting and consuming coffee, for the crew of Itasca and Howland Island, 8:43 a.m. was a special time. But 2013 GMT (8:43 a.m.) was also the 20-hour mark for the fliers, after their own, even more stressful all-nighter. Sadly, the two in the Electra, at 13 past 20 hours, were entirely on their own at 2013 — and here that sinister number “13” appears again.

Radio room of USCG Cutter Tahoe, sister ship to Itasca, circa 1937. Three radio logs were maintained during the flight, at positions 1 and 2 in the Itasca radio room, and one on Howland Island, where the Navy’s high-frequency direction finder had been set up. Aboard Itasca, Chief Radioman Leo G. Bellarts supervised Gilbert E. Thompson, Thomas J. O’Hare and William L. Galten, all third-class radiomen, (meaning they were professionally qualified and “rated” to perform their jobs). Many years later, Galten told Paul Rafford Jr., a former Pan Am Radio flight officer, “That woman never intended to land on Howland Island.”

The following routing and times are a compilation from several sources:

(1) Itasca Logs from the log-positions on the ship, a copy of which can be provided;

(2) Notes from Harry Balfour, local weather and radioman on site at Lae;

(3) Notes from L.G. Bellarts, Chief Radio operator, USS Itasca;

(4) The Search for Amelia Earhart, by Fred Goerner;

(5) Amelia Earhart: The Truth At Last, by Mike Campbell;

(6) David Billings, Australian flight engineer (numbers questionable), Earhart Lockheed Electra Search Project;

(7) Thomas E. Devine, Vincent V. Loomis, and various other writings.

The intended course for the Electra was a direct line from Lae to Howland covering 2,556 statute miles. The actual track, however, was changed due to weather, in the first instance, and due to a change of decision in the second instance. Such contact never took place. Neither the Electra nor the Ontario saw nor heard from the other, for reasons which could have been avoided if each had known the frequencies and limitations of the other. This basic lack of communication plagued almost every radio and key which tried to communicate with the Electra.

If one has access to Google Earth, it is interesting to pin and to follow this flight by the hour. The average speeds and winds were derived from multiple sources, including weather forecasts and reports.

To generalize, the average ground speed going east was probably not above 150 mph, with a reported headwind of some 20 mph, which began at about 135-140 mph when the plane was heavy and struggling to climb.

In the beginning, with input from Lockheed engineers, Amelia made a slow (about 30 feet per minute) climb to 7,000 feet (contrary to the plan laid out by Lockheed’s Kelly Johnson), then to 10,000 feet (which should have been step-climbing to 4,000 to 7,000 to 10,000 feet toward the Solomons mountain), then descending to 8,000 feet depending upon winds, then to 10,000 feet reported, with various changes en route.

The remaining contingency fuel at 8:43 a.m. Howland time, to get the Electra back to the Gilbert Islands, as planned out carefully with the help of Gene Vidal (experienced aviator) and Kelly Johnson (experienced Lockheed engineer), has often been, in our opinion, mischaracterized and miscalculated. By all reasonable calculations, the Electra had about 20 hours of fuel PLUS at least four-plus hours of contingency fuel.

July 2, 1937: Amelia Earhart, leaving Lae, New Guinea, frustrated and fatigued from a month of pressure, problems, and critical decisions on a long world flight, and unprepared for the Radio issues ahead, unprepared, that is, unless there was a bigger plan in play.

Then why did Amelia say she was almost out of fuel when making one of her last calls at 1912z (7:42 am)? Obviously, she was not because she made another call an hour later about the “157-337 (sun) line” at 2013z. Put yourself in that cockpit, totally fatigued after 20 hours of battling wind and weather and loss of sleep, compounded by 30 previous difficult days. It is easy to see four hours of fuel, after such exhaustion, being described as “running low.”

With the desperation of wanting to be on the ground, it would be quite normal to say “gas is running low” just to get someone’s attention. If one is a pilot, and has ever been “at wit’s end” in a tense situation, they have no problem not being a “literalist” with this statement. The subsequent facts, of course, substantiate this.

An undated view of Howland Island that Amelia Earhart never enjoyed. Note the runway outline many years later, a destination which became a ghost. In the far distance to the left, under thick clouds at 8:13 a.m. local time, was “Area 13.”

Wherever the Electra ended up, and we have a volume of evidence for that in a future posting, IT WAS NOT IN THE OCEAN NEAR HOWLAND. That was a government finding as accurate and as competent as the government’s success was against the Wright Brothers’ attempt to make the first fight.

For this leg of the Electra’s flight to its destination, our starting data point was Lae, New Guinea, and our terminal data point is not the elusive bird-infested Howland Island, but rather the area where they were often said to be “lost,” a place we have designated as Area 13. (A more detailed flight, by the hour with data from the Itasca logs, is available. Enjoy the trip.

Summary of track from Lae to Area 13 then to Mili Atoll (times are approximate):

(1) LAE to CHOISEUL, Solomon Islands – Total Miles: 670 / Total Time: 05:15 hours

(2) CHOISEUL to NUKUMANU Islands – Total Miles: 933 / Total Time: 07:18 hours

(3) NUKUMANU to NAURU Island – Total Miles: 1,515 / Total Time: 11:30 hours

(4) NAURU to 1745z (6:15 a.m. Howland) – Total Miles: 2,440 / Total Time: 17:45 hours

(5) 1745z to 1912z (7:12 a.m. Howland) – Total Miles: 2,635 / Total Time: 19:12 hours

(6) 1912z to 2013z (8:43 a.m. Howland) – Total Miles: 2.750 / Total Time: 20:13 hours

LAE to AREA 13: Total Miles : 2,750 (Including approaches) Time: About 20:13 hours

Fuel Remaining: About 4.5 to 5 hours

Distance from 2013z to Mili Atoll Marshall Islands = About 750 miles

Ground speed = 160 (true air speed) plus 15 mph (tailwind) = 175 mph

Time en route = About 4.3 hours

ETA at Mili Atoll, Marshall Islands = Noon to 12:30; Fuel remaining: 13 drops

NOTE that from a spot about 200 mi NW of Howland (Area 13) to the Gilberts is not the same heading as to the Marshall’s Mili Atoll. The Gilberts are the three small islands below Mili Atoll. The “Contingency Plan” was to return to the Gilberts and land on a beach among friendly people. Instead, they made an “intentional” decision to pick up a different heading toward the Marshalls whose strong Japanese radio at Jaluit they could hear. Compare the two different headings from Area 13 to the Gilberts and to the Marshalls. The difference is about 30 degrees. THEY ARE NOT THE SAME. Did they make an honest mistake, or an intentional decision?

The heading to the Gilberts would not have taken them to the Marshall Islands, with a heading difference of about 30 degrees. The decision to give up on Howland, and utilize the remaining contingency fuel was “intentional,” not merely intentional to turn back, but to turn toward the Marshalls where there was a strong radio beam, a runway, fuel — and Japanese soldiers who may or may not be impressed with the most famous female aviator in the world. Amelia and her exploits were known to be popular in Japan at that time. Although their mind was on war with China, maybe this charming pilot could tame them.

Unfortunately, we know THE END of the Amelia story, and it was not pretty. When she crossed into enemy territory, she apparently lost her charm with the war lords, and eventually her life. (End of Part III.)

Next up: Part IV of “Amelia Earhart: Disappearing Footprints in the Sky.” As always, your comments are welcome.

![Fishing boat story 5 This story appeared at the top of page 1 in the July 13, 1937 edition of the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania)-Globe Times. “Vague and unconfirmed rumors that Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan have been rescued by a Japanese fishing boat without a radio,” the report began, “and therefore unable to make any report, found no verification here today, but plunged Tokio [sic] into a fever of excitement.” The story was quickly squelched in Japan, and no follow-up was done. (Courtesy Woody Peard.)](https://earharttruth.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/fishing-boat-story-5.png?w=616&resize=616%2C352#038;h=352)

Recent Comments